The panic behind Botswana’s big, sparkly diamond show

Diamonds account for 30% of Botswana’s entire economy. But lab-grown gems mean less demand for ones dug out of the soil.

Keletso Thobega in Gaborone

Diamonds account for 30% of Botswana’s entire economy. But lab-grown gems mean less demand for ones dug out of the soil. For now, Botswana is trying to get more control over the money still to be made from its precious stones.

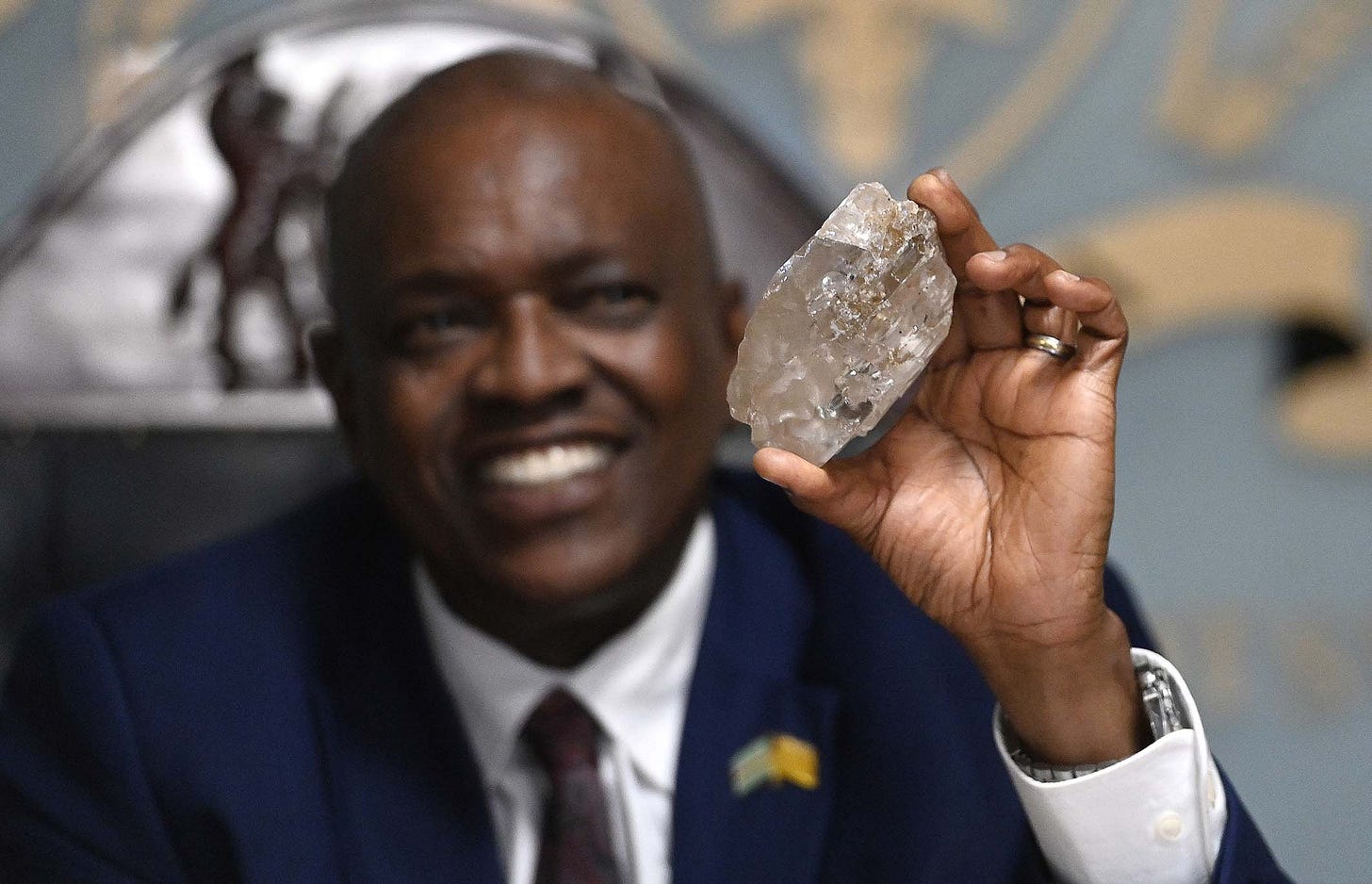

Diamonds are how all presidents of Botswana have seen roads built since 1967. Last week was no different. When he unveiled the largest diamond to be mined this century, President Mokgweetsi Masisi exclaimed: “I can see new roads being built.”

The translucent gem is the size of an adult’s palm. The second-largest diamond ever found, it could sell for tens of millions of dollars. And 10% of that will go to Botswana because, unlike other countries rich in raw materials, the southern African state has kept its seat at the table. Through agreements with mining companies, it earns crucial dollars and keeps a share to sell for itself.

But Masisi has to work harder than his predecessors to keep the cash cow alive. Botswana is the world’s biggest producer of mined diamonds by value, and mines 20% of all diamonds, by weight. That value is falling rapidly thanks to lab-grown diamonds. These are cheaper and hardly distinguishable from mined ones.

In January, the middle-income country estimated that its economy would grow by 4.2%. But then diamond sales nearly halved in the first three months of the year. Last month, the IMF changed its own estimate and said the economy would only grow by 1%. It also advised the country to spend less on infrastructure because it would have less money.

Seeing the shifting market, Botswana has started to change its diamond marketing strategy and invested in making splashier announcements: big rare finds that make international news.

Canadian miner Lucara Diamond has helped. The Karowe mine, 500km north of the capital Gaborone, gave up this diamond after two other big finds in its 12 years of operation. One of these was reportedly sold for over $50-million. Last week’s 2,492-carat stone was found using x-ray technology designed to identify and preserve large, high-value diamonds so that they can be extracted whole.

But discovery of rare, highly sought-after stones is “not the basis for an industry”, says mining historian Duncan Money. “Ultimately, it doesn’t change the fact that synthetic diamonds are becoming cheaper and better.”

So Masisi’s other bet is to swing for more of the pie – even as it dwindles.

Last February, he threatened to sever ties with Anglo American, which with Botswana co-owns mining giant De Beers, and local miner Debswana, which runs four of Botswana’s five active diamond mines.

Masisi’s critics accused him of nationalist rhetoric but when the Debswana arrangement was renewed (in principle) a few months later, the halfcentury partnership had some crucial new changes. Where Debswana used to only be able to sell 25% of its diamonds to the state-owned Okavango Diamonds marketing company, it can now sell 30%. And that number will grow to 50% over the next 10 years.

The rest will still go to De Beers, in which Botswana has a stake of 15%. In addition, De Beers will invest a billion pula ($75-million) into a fund for development, ramping that up to 10-billion over 10 years.

The Botswana government’s work to protect its diamond income also means keeping others out. This May, when Anglo American announced it would split from De Beers, Masisi said Botswana was prepared to buy more of a stake in the spin-off, to keep out “bad guys” with “impatient capital”. De Beers made only $72-million last year – which is a bust in the diamond industry. But its profits have historically ranged between $500-million and $1.5-billion, according to Mining Weekly. Its target is to return to an annual core profit of $1.5-billion by 2028.

Masisi reckons that if Botswana puts enough public money in the game to patiently ride out the booms and busts of the erratic diamond industry, he and his successors will continue building roads, schools and hospitals. Others, like Money, reckon it’s time for Botswana to start diversifying its economy instead.