Diamonds are not forever

Shaped for generations by the wild profits of its extractive industries, South Africa is contemplating a bleak post-mining future.

Kiri Rupiah in Johannesburg

Anglo American, the London-listed South Africa-founded mining giant, has certainly seen better days. In February, it posted a 94% drop in annual profits, prompting its shareholders to lose their collective minds. Weeks later, it started getting what some analysts have called “insultingly cheap” offers for a takeover. This week, the company announced the most radical changes to its structure in decades: breaking up the family heirlooms, and selling them off.

In a Tuesday statement, Anglo said it will either break up with, or sell, De Beers, which has been in the group since 1927. De Beers – the diamond miner founded by Cecil Rhodes in 1888, and later run by the Oppenheimer family – may be listed separately on the London Stock Exchange, according to Reuters. The government of Botswana holds a 15% stake in De Beers.

Anglo American also announced that it will demerge from South Africa-based platinum producer Amplat, in which it is a majority shareholder, and sell its steelmaking coal mines in Australia.

These radical changes have come in response to a take-over bid by the world’s largest mining company, BHP, which offered to buy Anglo for $42.7-billion earlier this month. The offer, like a cheaper one made last month, was rejected. But it has put Anglo executives under pressure to give their shareholders better options.

That this storied company – which for decades was South Africa’s wealthiest – is in this position at all is because of the falling prices of both diamonds and platinum. Platinum is likely to recover, but diamonds may have lost their shine forever. Industrial or lab-grown diamonds are very similar to natural diamonds, but don’t cost as much to produce. “There’s also been less demand for jewellery and many analysts don’t see a future in diamond mining,” mining historian Duncan Money told The Continent.

Anglo’s best-performing assets are its copper mines, which is what BHP is really after. Since the early 1990s, Anglo has pushed to expand globally, acquiring copper mines in Chile and Peru, ahead of an expected copper boom. Demand for the metal, which conducts electricity, is growing as the world shifts to renewable energy and electric vehicles.

Its proposed restructuring will allow the company to focus on its copper business, and – by ditching its expensive diamond and platinum operations – free up $1.7-billion a year to do so. Shareholders seem to be buying this new vision: Anglo American’s share price, which shot up after the BHP offer, continued to rise after Tuesday’s announcement.

It may not be such good news for southern Africa, a region Anglo American has exploited for generations. Despite the company’s controversial history – it has been accused of trashing the environment and exposing its workers to deadly diseases – it remains one of South Africa’s largest employers and taxpayers.

“It’s been bad, but once they leave, it may grow even worse,” said Money. “There’s nothing coming to replace these mines and the livelihoods of millions will be affected.”

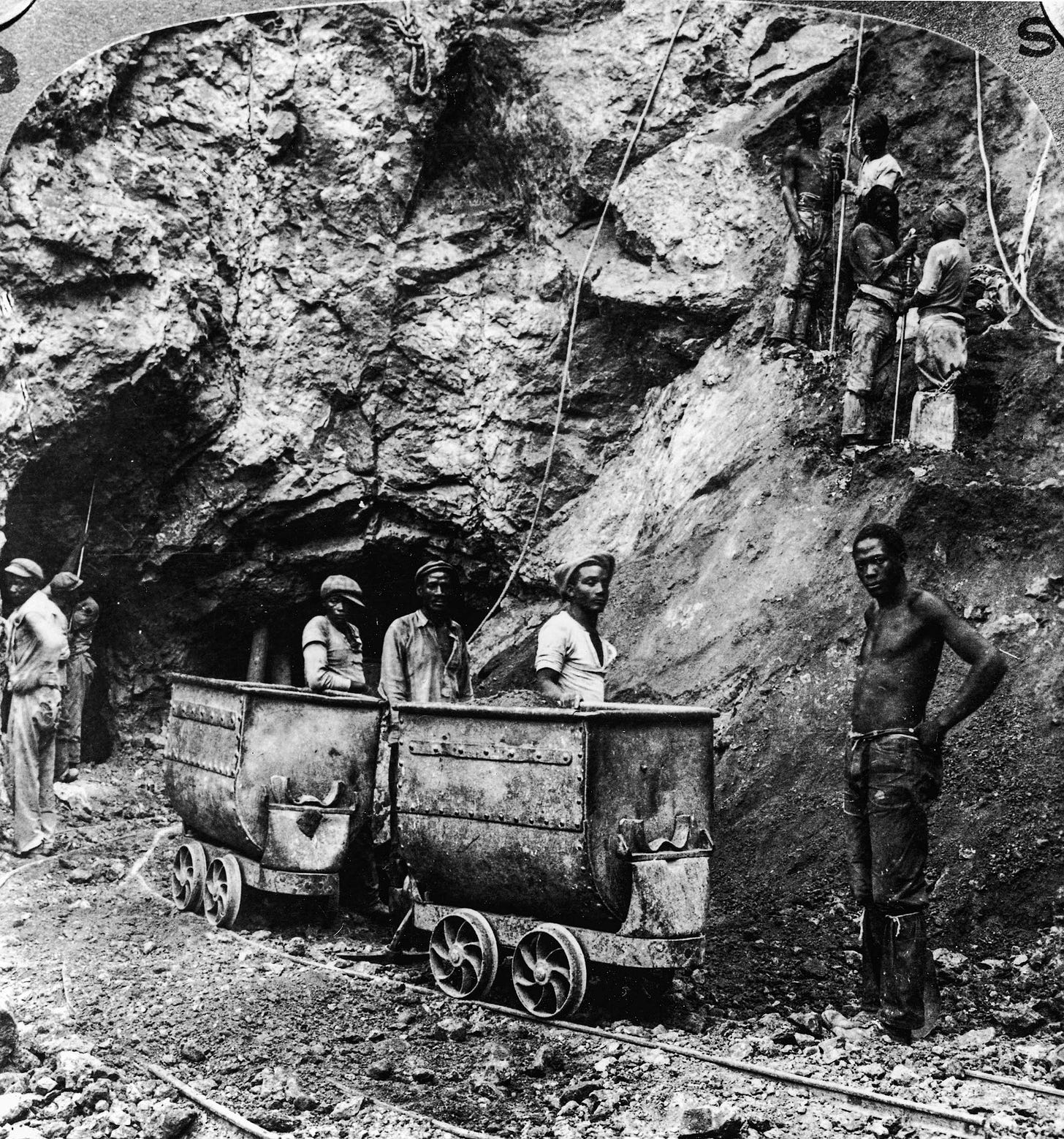

It is on these grounds that South Africa’s mining minister, Gwede Mantashe, and its largest trade union, Cosatu, have opposed BHP’s bid. BHP proposes to spin off Anglo’s South African assets, arguing that they are no longer profitable enough. “These companies were built on the back of South African mineworkers and pension funds,” Cosatu said. “The profit they generate is needed to grow the economy and create decent jobs.”

This may be true – after all, mining has underpinned South Africa’s economic growth for over a century. But the country may need to adapt to a new reality, and quickly. “Mining is in a downturn now and there’s a possibility it will never pick up again.That’s something that’s not widely appreciated, especially in South Africa, where there is a sense that mining will be there forever,” said Money.