Occupation tests Bukavu’s century-long resilience

Wrapped along Lake Kivu’s shores, the city’s streets and buildings tell the story of the decades of struggle over who runs this part of the DRC.

Prosper Heri Ngorora

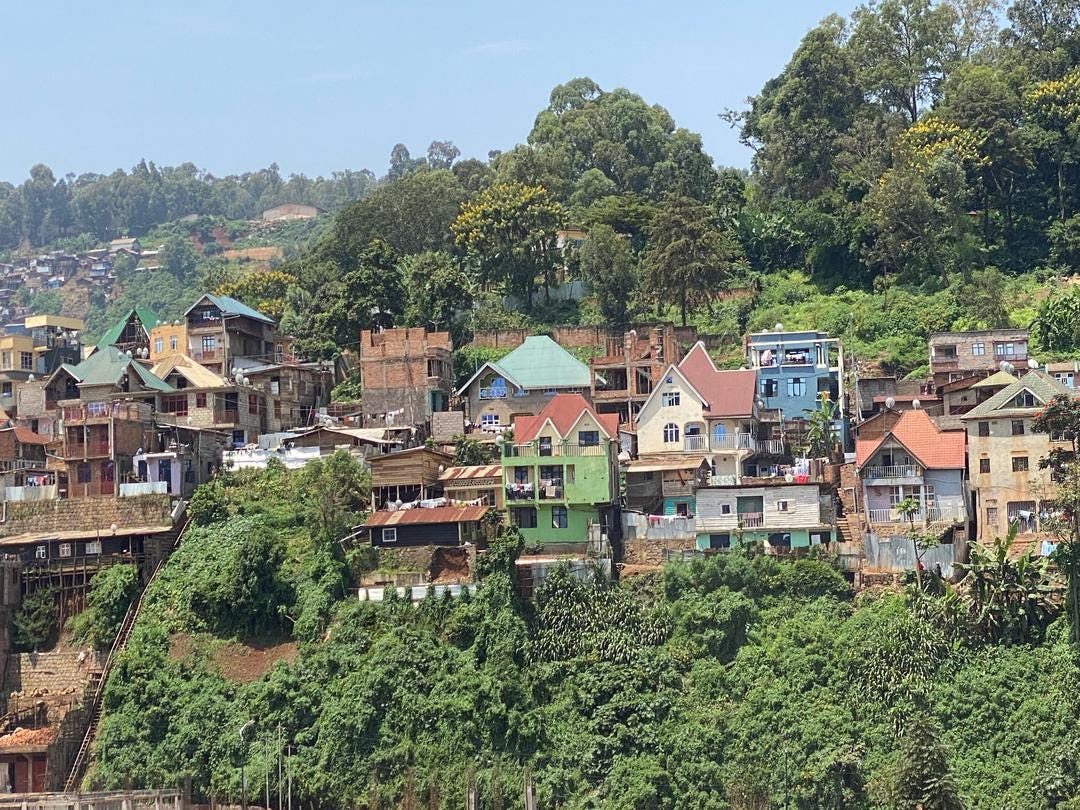

Bukavu’s clay-loam soils hug its lakeside cliffs and hills to create a city that is almost bewilderingly beautiful. A peninsula, the city juts into Lake Kivu in five sections that from a distance look like a green palm floating on the water.

From the lake, whether you arrive by boat, fast canoe or pirogue, the closer you get, the more the city’s Western-style art deco buildings come into focus.

Near the shores, colonial-era villas stretch out to touch the lake. The Hôtel Résidence boasts a century-old elevator. A night there costs as much as $175. It sits on another reminder of the country’s changing history – the Avenue PE Lumumba.

At the heart of old Bukavu, the Place de l’Indépendance public square has statues to DRC figures like Patrice Lumumba and Laurent-Désiré Kabila.

Built as the colonial administrative centre of the Kivu region, Bukavu used to be called Costermansville, after a Belgian vice-governor who is said to have killed himself after details of the genocide committed by Belgium came out. Its importance waned with the growth of Goma on the other end of Lake Kivu. It is now home to more than a million people.

Most of those people live further from the shore, in the low cost houses that cling to the city’s hills. Jean-Luc Chiza Chito, a human rights activist, says these are people who “make their living from manual labour, such as masonry, plumbing and carpentry”.

Chito has lived in Bukavu for more than 20 years. Policy heads like him gravitate towards the city more than to its better known “twin city” Goma, whose raison d’etre is trade. To this day, it remains a city where almost everyone likes to discuss politics, says Byamungu Samuel, who co-ordinates citizen movements and pressure groups in South Kivu.

A new kind of politics is in town when The Continent visits in late February. Two weeks prior, Bukavu was occupied by the Rwanda-backed M23 rebels. There is evidence of recent looting across the town: broken shop doors and empty shelves. And the new administration’s decision to suspend all the employment of all civil servants has chilled the streets further.

In a press release, M23 said the suspensions were temporary: “It’s all part of the post-war assessments and with a view to optimising the reorganisation of the state’s public services.”

Mika Kasi, who worked at the Bukavu town hall, certainly hopes so. “Living in this time of war is complicated. It will be difficult for me to take care of my family,” he complains. Careful not to sound too critical, he adds: “But it’s just a matter of time before we’re back at work.”

Like in Goma, the wider Bukavu economy is strapped for cash since the M23 occupation isolated the city from the rest of the DRC. Many banks are still closed and big employers like the Kiliba sugar factory, Bralima breweries and Pharmakina have suspended activities.

Instead, Bukavu residents are being put to unpaid work. “The new authorities have introduced community sanitation work, which is making the city cleaner and cleaner,” says Patient Bisimwa, who used to repair electronic equipment before looters stole customers’ property from his shop.

There will be dire consequences if the cash economy doesn’t recover soon, says human rights activist Chito. “People are living in abject conditions. Many live by manual labour. When they don’t work, hunger threatens to exterminate them.”