Zimbabwe’s ruling party recruited people to vote – in Mozambique’s election

Ahead of last year’s Mozambican election, Zanu-PF dished out fake IDs to its supporters, with clear instructions to vote for the incumbents next door. Some of them were actually undercover reporters.

Walter Marwizi and Garikai Mafirakureva

The rumours began in early 2024. We work as journalists in Masvingo, a province in the south-east of Zimbabwe, and we kept hearing that our own ruling party – Zanu-PF – was recruiting Zimbabweans to vote in Mozambique’s presidential elections in October. We were sceptical. The idea that one country’s ruling party could be signing up people, in broad daylight, to meddle in a neighbour’s election seemed too outlandish to be true. It would amount to brazen electoral fraud. But, by April 2024, we had heard too many stories to ignore the possibility.

One morning in April, a Zanu-PF supporter – and one of our trusted sources – showed up at the Masvingo Mirror’s offices with a tip-off. He told us to visit a voter registration station in nearby Nemanwa.

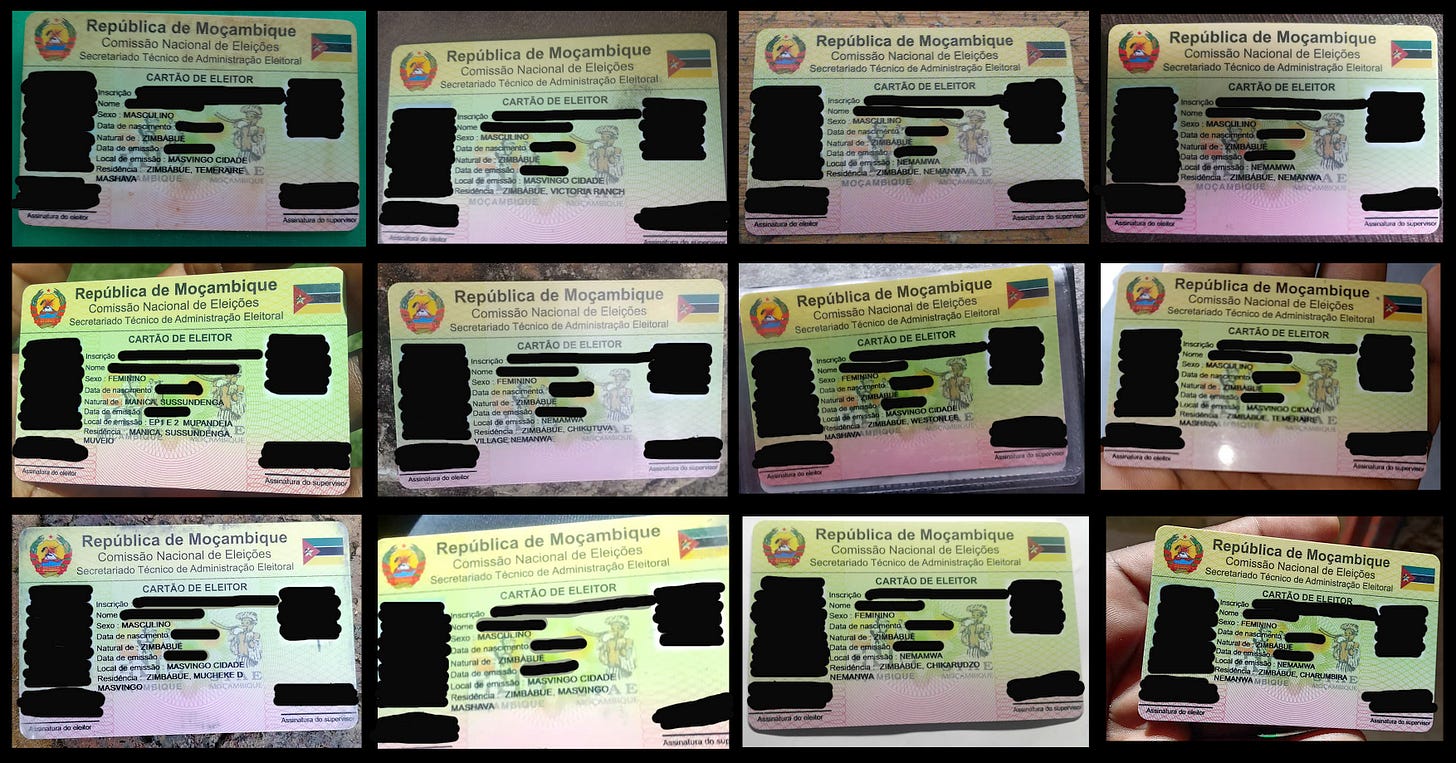

That afternoon, there was a queue of hundreds at the scene – the Masvingo Rural District Council offices. The next morning one of us joined the queue, had our fingerprints and photos taken, and left with a glossy, newly-printed Mozambican voter identification card.

On another occasion in April, the other of us went to Nemanwa to register. A lady at the gate asked for names, addresses and phone numbers, and said we would be invited to Zanu-PF party meetings to receive instructions to “help Frelimo win the election”. Frelimo is Mozambique’s ruling party, which was facing stiff opposition in the upcoming election.

Inside, fingerprints and a photograph were taken, and we left, again, with a newly-printed Mozambican ID card.

Still, we were unsure whether those cards would actually allow us to vote.

There are some Mozambicans residing in Zimbabwe, and Mozambique’s electoral commission had approved 60 polling stations within Zimbabwe – as part of 602 foreign polling stations in nine countries with significant Mozambican diasporas.

“This presented us with an opportunity,” a senior Zanu-PF official told us later, speaking on condition of anonymity. “The challenge was to attract as many people to register as possible.”

On Mozambique’s voting day, 9 October 2024, Zanu-PF officials threw stones at us when they noticed us filming. But at another polling station in Nemanwa, we walked right in. There, we were given the opportunity to cast our ballot in Mozambique’s general election – no questions asked. The whole process took less than half an hour.

We have since interviewed 20 other Zimbabweans who fraudulently registered, and in some cases voted, in Mozambique’s election.

Old buddies, new tricks

The alliance between Zanu-PF and Mozambique’s ruling party Frelimo is one of the strongest political pacts in Africa. It dates back to the days of the liberation struggles in both countries. As the October 2024 election loomed, Frelimo felt threatened by the growth of opposition parties like Renamo and Podemos. It appears to have leaned into the old pact for support.

Months before the election, Daniel Chapo, the Frelimo candidate – he is now the president – travelled to Harare and met President Emmerson Mnangagwa and top Zanu-PF officials.

“We know Zanu-PF is experienced in terms of elections. We want that campaign spirit in Mozambique,” Chapo said during the June 2024 visit.

But, as our reporting shows, Zanu-PF’s electoral support to Frelimo had been going on for months prior. This support extended well beyond transferring the “campaign spirit” to Mozambique.

The testimonies of those 20 Zimbabweans we spoke to – all fraudulently registered as Mozambican voters – confirm that the party undertook a co-ordinated campaign to mobilise voters in support of Frelimo.

“I joined those who voted because I saw it as a chance to prove that I’m a loyal cadre, and to try and save my house,” said GZ. He lives in a former mining compound from which he can be evicted at the whim of Zimbabwe’s government. Another person, SZ, said he heard about the registration drive through party channels and participated because he believed it was his duty to serve the party.

SZ said he also voted in the 2019 Mozambican election and therefore saw last year’s mobilisation drive as routine. He was not the only one to say this.

GM, another repeat voter, said that after the 2019 Mozambican election, Frelimo organised trips for its Zimbabwean supporters to shop in Chimoio, a major market, for secondhand clothing in Mozambique. “The trip was profitable. We brought back secondhand clothing for resale. I hoped this time we could go again,” GM said.

The expectation of trade opportunities was a recurring rationale.

EM, a 28-year-old who works in Mutare’s banana plantations, had long dreamed of becoming a crossborder trader, but the steep price of a Zimbabwean passport had kept them from that dream. When they heard that one could get a Mozambican identity card in exchange for voting for Frelimo, they jumped at the opportunity.

“They took my fingerprints and photo and I waited briefly before I got a Mozambican card,” they said. The card said that they were born in Manica, Mozambique. EM did not mind that it was not true because now they could travel freely to Mozambique.

LK told us that she had never been to Mozambique, but also registered due to the promise of free passage to Mozambique to buy goods for resale in Zimbabwe. So she voted, hoping that she would be able to become a vendor.

“I’m not Mozambican, and I was not doing it to help Mozambique. I know that Mozambique, especially Frelimo, helped Zimbabwe during the liberation struggle, but that’s not why I voted,” she said.

Similarly, SN was thrilled that her voter ID card could give free passage to buy goods in Mozambique.

In contrast, DM, whose mother is Mozambican, felt he had some right to vote and was being helpful to Mozambique. “When my colleagues in Zanu PF approached me to participate in the Mozambican elections, I felt it was a chance to help my mother’s country. I didn’t expect anything in return,” he said.

Fait accompli

Stories like DM’s are what Zanu-PF has used to justify the registration drive – when they have acknowledged it at all. When the Masvingo Mirror first reported on this issue late last year, Zanu-PF spokesperson Chris Mutsvangwa said these people were in fact dual citizens of both Mozambique and Zimbabwe, who had been given an opportunity to exercise their political rights.

He now says the matter is moot.

“The Mozambican election is over. President Chapo is now recognised by the international community. Recently President Trump even gave him $4.5-billion. So, it won’t matter now whether they had dual citizenship or not. Why do you always look in the rear view mirror? Try to look in front of you,” Mutsvangwa told us last month, before dropping the phone call.

Farai Marapira, who heads Zanu-PF communications at national level, refuted the allegations, saying that Mutsvangwa must have misunderstood our questions.

Frelimo spokesperson Pedro Guileche told The Continent that these allegations are “truly fake”, adding that: “Frelimo still has the wider range of Mozambican people voting and supporting our party and consequently our President Daniel Chapo, from Rovuma to Maputo.”

While our reporting provides rare proof of the fraud, allegations have long been rife that the 2024 Mozambican election was rigged. The heavily contested result triggered three months of nationwide demonstrations by opposition supporters. According to local activists, at least 300 people were killed by security forces, and 10 times more were injured.

Negotiations to move the country forward continue. President Chapo met his main challenger, the opposition leader Venâncio Mondlane, for the second time this week.

In an interview with The Continent earlier this year, Mondlane maintained that the election was rigged – describing Chapo as an “appointed” president, rather than elected. As our reporting proves, he may have a point.

Wow. Just, wow. Great reporting!