Yeelen, the light that endures

The pioneering work of Souleymane Cissé will live on for many generations to come.

Wilfred Okiche

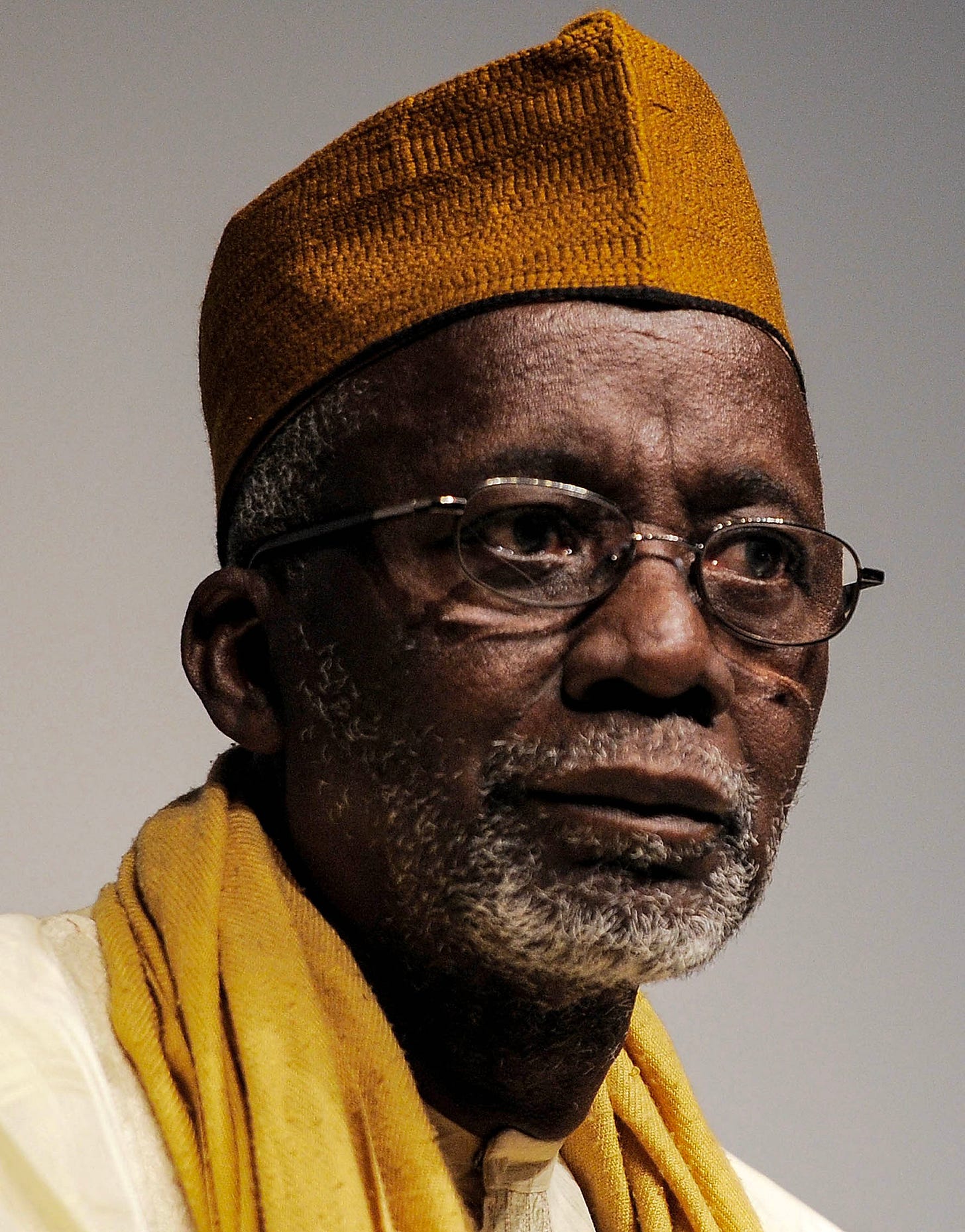

Souleymane Cissé, the legendary Malian director who died on 19 February, was – alongside the likes of Ousmane Sembène and Sarah Maldoror – part of the pioneering generation of African filmmakers. Dying at the age of 84, Cissé had embodied film history.

Cissé was trained in Moscow before returning home to make his movies. His f ilmography consists of seminal entries like Baara (Work), Finye (The Wind) and Waati. But it was his masterpiece Yeelen (Light) that altered the very essence of African film-making and gave Cissé immortal status. Released in 1987 at the Cannes Film Festival – where it became the first film by a Black African to score a jury prize – Yeelen is a stunning stylistic achievement.

The film dazzlingly repurposes oral folklore native to Cissé’s Bambara culture, and its circular interpretation of time, to reconceive Africa’s past and future selves.

This reset conventions in cinema.

It said that African films didn’t need to be limited to traditional modes of social realism and filmmakers didn’t need permission to imagine worlds or upend the colonial gaze because cinema is an indigenous artform.

The story of Yeelen is the story of Mali, allegorised in the 13th century mythical saga of Nianankoro (Issiaka Kane), a young wizard who journeys across land and dreamscapes to do spiritual battle with his corrupt father, in order to claim his destiny.

While celebrating West African cosmology, Yeelen also critiques the corruption of power while predicting the suffering that is to follow the transatlantic slave trade. But Cissé also advances a hopeful message of salvation and rebirth, powered by a light that is almost unbearable.

Yeelen is furiously inspired and immaculately detailed. It’s a highwater mark not only in African cinema. Martin Scorsese is a big fan. So too is Mati Diop, whose Cannes debuting stunner Atlantics quietly references Yeelen.

The film’s indelible imagery – a woman bathing in milk, a child retrieving an ostrich egg – endures by itself. But it is also in the work of auteurs like Phillip Lacôte (Night of the Kings), Baloji (Omen) and CJ Obasi (Mami Wata). Such is the endurance and transcendence of the legacy of the film and its creator.

Yo, I love Cissé and I love getting this newsletter dropped in my email every morning but damn, maybe throw a little content warning up if you're gonna include some dying animals maybe? I had forgotten about the rooster sacrifice and it wasn't my most-favorite way to start my day...