Why did South Africa’s president gladhand a genocidal general?

Invoking the spirit of Nelson Mandela, facilitators of the controversial Hemedti-Ramaphosa meeting say this is how peace is made. But not everyone is convinced by the explanation

Jesse Copelyn in Cape Town

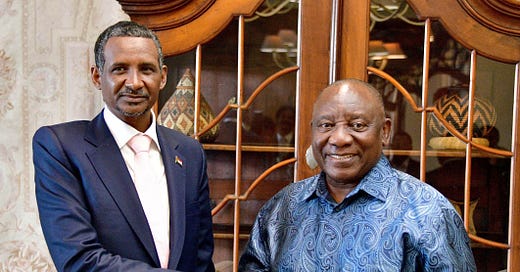

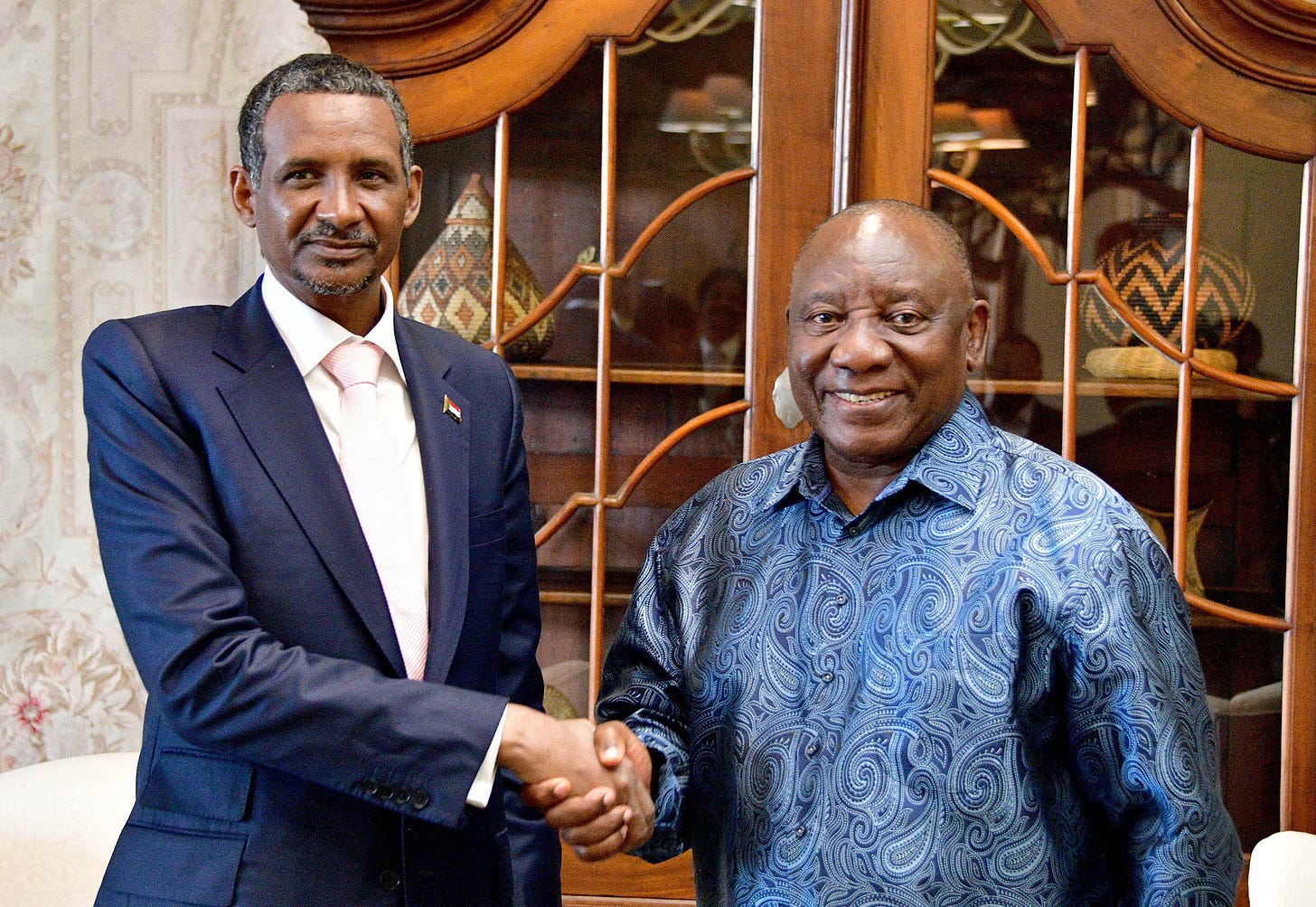

On 4 January, a beaming Cyril Ramaphosa shook the hand of Sudanese militia leader General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, commonly known as Hemedti.

The meeting took place as Sudan’s civil war raged on, with both sides accused of human rights abuses. In one case, in an advance on El Geneina in Western Darfur last year, Hemedti’s militia killed as many as 15,000 people, many belonging to the Masalit ethnic group. He is also implicated in the genocide in Darfur in the early 2000s.

Hemedti’s stop in Pretoria was part of a continent-wide trip to shore up support and gain legitimacy. Sudan is still technically led by his former ally and now opponent, General Abdul Fatah al-Burhan, who controls the army.

The backlash to the meeting included accusations that it was hypocritical and inconsistent with South Africa’s post-apartheid values of equality and justice.

It also came in the very same month that South Africa took Israel to the International Court of Justice, accusing it of genocidal acts in Gaza.

Vincent Magwenya, Ramaphosa’s spokesperson, said that this was “not a meeting between two heads of state” but rather a gesture of courtesy.

The nonprofit that helped organise the meeting, the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes, has invoked Nelson Mandela in defending it.

Its executive director, Vasu Gounden, told The Continent: “Mandela said you can’t make peace by talking to your friends.”

Gounden was in the meeting and said South Africa would meet with all the sides to a conflict in Africa. “If Burhan gets on a plane and comes tomorrow to meet with Ramaphosa, Ramaphosa would meet him.”

Hemedti’s forces, which The Continent has previously reported are supported by the United Arab Emirates, currently have the upper hand in the war, controlling key parts of the capital Khartoum; Wad Madani, a major city south-east of the capital; and most of Darfur.

In his tour, Hemedti also went to Uganda, Ethiopia, Kenya, Djibouti and Rwanda. But the South Africa leg was particularly important, according to Sudanese political analyst Kholood Khair.

The handshake – with the leader of a stable democracy – showed that Hemedti “is not only meeting despots”, said Khair.

She said the reception in Pretoria and other capitals also showed that presidents “consider Hemedti to be presidential material, if not president in actual fact”.

She pointed to the quickly-deleted tweet by South Africa’s government that referred to Hemedti as Sudan’s president.

These steps also serve to weaken al-Burhan’s position.

Cameron Hudson, an analyst and former director of African Affairs at the White House’s National Security Council in the United States, said that while mediation would require meeting with Hemedti, Ramaphosa seemingly has “no particular interest in being involved ... in bringing an end to this conflict”.

Others also claim that Hemedti’s reception across Africa was helped by the UAE’s outsized influence on the continent.

The UAE has denied accusations that it has covertly been sending arms to Hemedti’s forces via Chad. A relationship exists, however: the paramilitary provided troops to the UAE and its partners in their devastating war in Yemen, which South Africa supported with arms.

Gounden denies that the UAE played a role in his organisation’s actions and said it has been involved in high-level conflict mediation efforts in Sudan since 2019.

More than 10.7-million people have been displaced since the start of the war and reports indicate that a victorious Hemedti could face revolutions at home and diplomatic isolation abroad.