Welcome to Addis Ababa (unless you’re homeless, ill, young or poor)

Earlier this month, the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission said that the crackdown on Addis Ababa’s indigent population amounts to a “violation of human rights”.

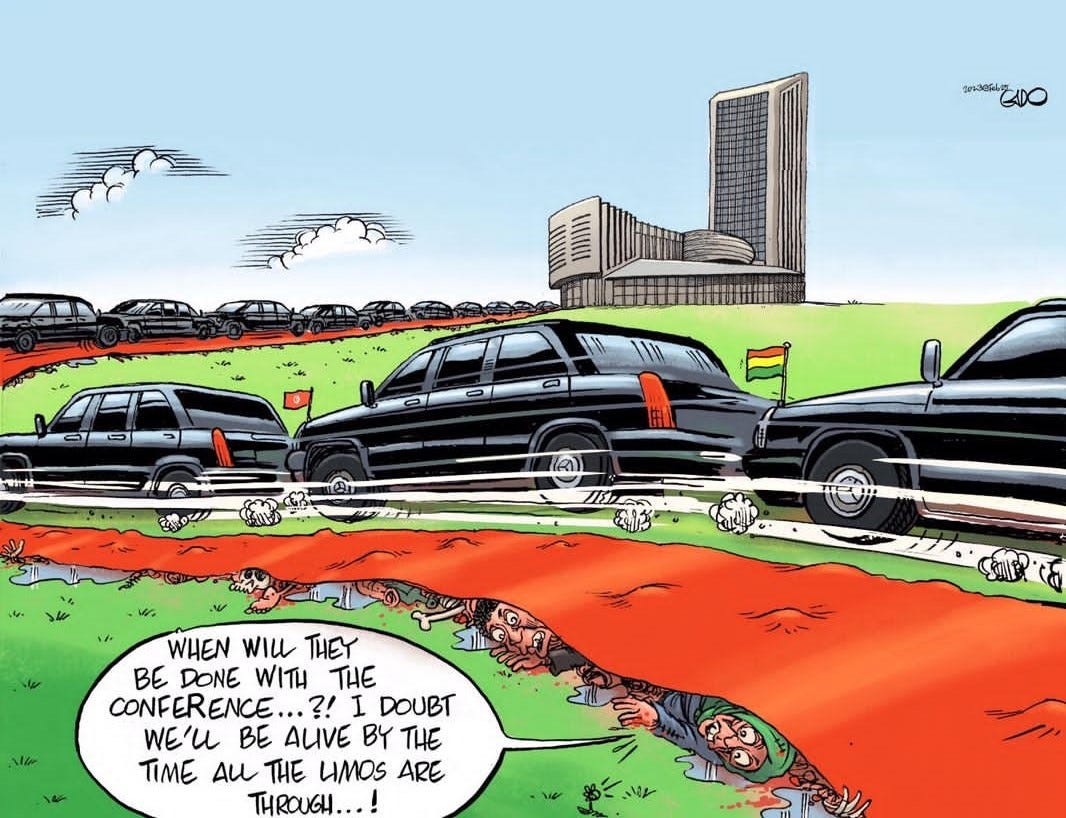

Ethiopia has a history of cleaning up the streets of the capital, Addis Ababa, ahead of major international conferences (as reported in issue 117 of The Continent). This includes the removal, by force, of the city’s beggars and homeless people.

But an operation conducted over the past few weeks by security forces appears to be more far-reaching. In the early hours of the night, thousands of poor residents in shacks and temporary dwellings have allegedly been rounded up and held in a detention centre on the outskirts of the city. From there, some are being forcibly relocated to their native provinces.

The Continent spoke to 27-year-old Henok Tsegaye, an engineer who got caught up in the crackdown. He came to the capital from Tigray after the end of the civil war, to reunite with his family and to find employment. His family home was demolished to make way for a government project, leaving them homeless.

Tsegaye was rounded up with dozens of others while looking for work on the streets, and taken to the detention centre. “We slept in the open air literally next to strangers. Open defecation was the norm, there were no mattresses, our safety was always compromised and water was extremely limited. I was extremely hungry,” he said.

Tsegaye feigned an illness in order to be transferred to a hospital, from which he managed to escape. “I am the reality of Ethiopia. I experienced war in Tigray when I could have been a productive citizen. I moved to Addis Ababa to find employment but even finding employment as a waiter became difficult. And now the appearance of being poor makes me a prisoner,” he said.

Earlier this month, the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) said that the crackdown on Addis Ababa’s indigent population amounts to a “violation of human rights”. It warned that conditions in the detention centre will increase the risk of a disease outbreak.

According to the EHRC, at least three civilians have already died in the detention centre which is located in Gelan Kifle Ketama in Oromia province. Many more have contracted illnesses or sustained injuries and require medical care.

“There are way too many people coming – weak and near death, with beating scars – to be discarded at our hospital,” said an administrator at the nearby Tirunesh Beijing Hospital, speaking on condition of anonymity. “There is little we can do to help them.”

In a statement, the Oromia regional government denied the existence of the detention centre, dismissing reports as “false information” to “confuse the public”. The office of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed did not respond to a request for comment.

Dreams deferred

In 2019 the mayor at the time, Takele Uma, promised to tackle homelessness among youth in Addis Ababa. Inspired by Chinese models, the plan was to set up a rehabilitation centre to train young people and then transition them into formal employment in one of the new industrial parks that were growing rapidly at that time.

This plan died abruptly when civil war broke out in 2020, and many foreign investors pulled their funding. Most significant was when the United States revoked Ethiopia’s benefits under the African Growth and Opportunity Act, which killed thousands of jobs in the industrial parks.

“I am the reality of Ethiopia. I experienced war in Tigray when I could have been a productive citizen. I moved to Addis Ababa to find employment but even finding employment as a waiter became difficult. And now the appearance of being poor makes me a prisoner.”

The existing homelessness issue was exacerbated by a wave of internal migration into Addis Ababa, with people fleeing conflict and looking for economic opportunities.

Among their number is Yared Kibret, a 19-year-old vendor from Amhara province, where fighting between government forces and the Fano militia is ongoing. He sells cheap belts and wallets on the streets near Meskel Square. In recent weeks, many of his friends – street vendors like him – have vanished.

Kibret does not know where they are, but he suspects they have been detained. He is worried that he will be next.

“I am mentally prepared for such an eventuality,” he said. “I just wish that working, instead of begging, would be my ticket to freedom.”