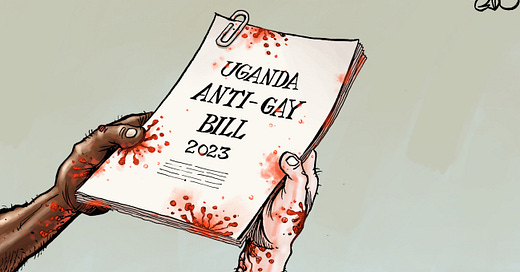

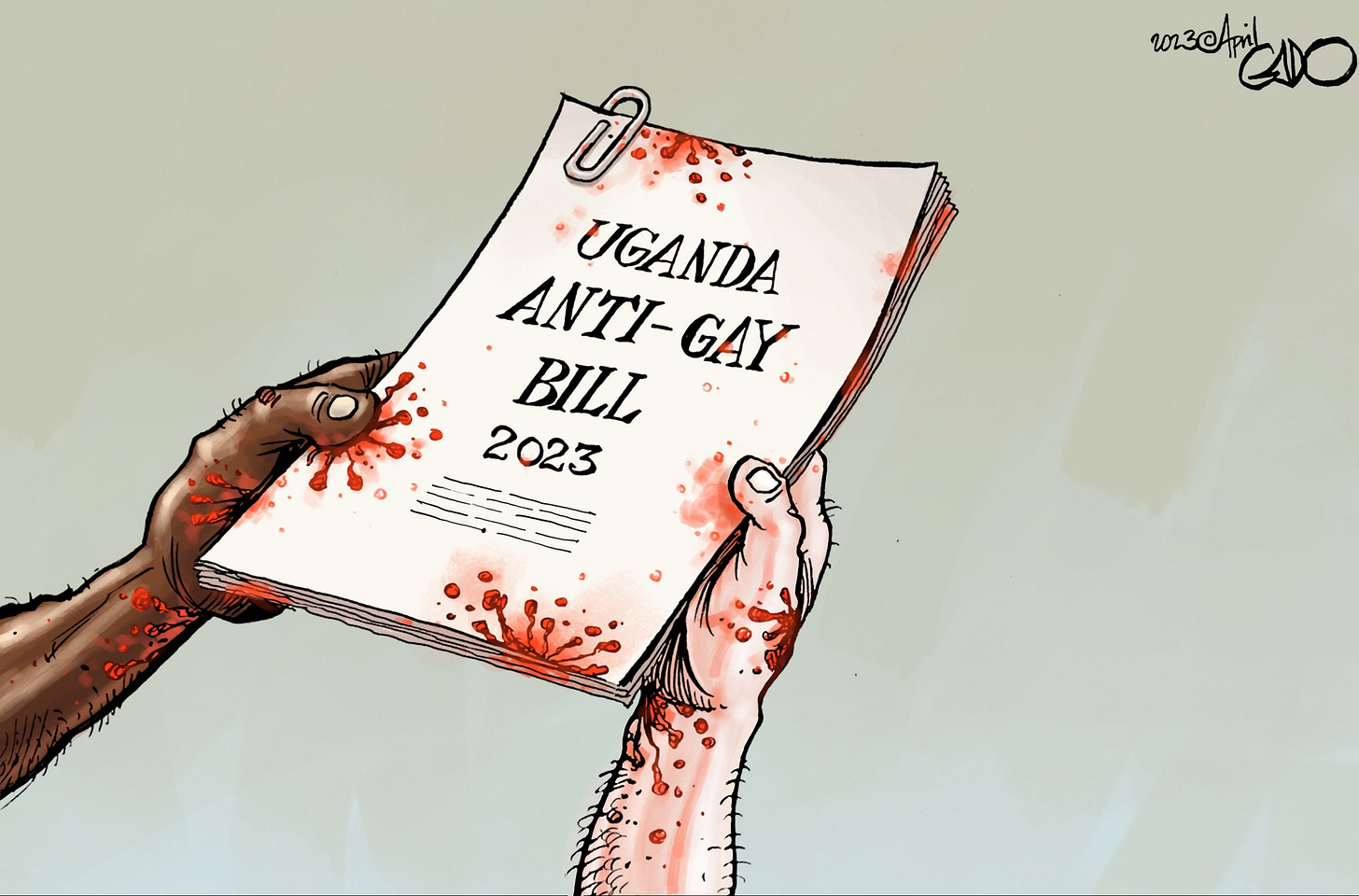

The western conservatives who set up the anti-gay bill

American citizens are key partners in the ultraconservative politics responsible for Uganda’s new anti-gay law, which sets the death penalty for homosexuals.

The US has condemned Uganda but remains silent on its own citizens.

On Tuesday, Uganda’s Parliament passed a largely unchanged version of the country’s harsh anti-gay bill. It allows for life imprisonment and the death sentence, in some cases. The law is an evolution of legislation originally introduced by colonial authorities. A previous incarnation, dubbed the “Kill the Gays” bill, was struck down by Uganda’s Constitutional Court in 2014.

Rights campaigners in the country say the current incarnation is the culmination of more than a decade of collaboration between Ugandan elite interest groups and American ultraconservatives. They say any international condemnation of the law should also target the Americans involved. “What I would expect [the West] to do right now is hold themselves accountable,” said Twasiima Bigirwa, a feminist writer. “This is not only a Ugandan problem. The kind of hate that we’re seeing in this moment is really inorganic. It’s been brought and stirred up by outsiders, and those outsiders need to be held accountable,” she added.

The Americans

Nonprofits registered in the United States and two American citizens have been linked to the political organising that set the stage for the bill, according to an investigation by UK-based openDemocracy.

Sharon Slater, the head of a US-registered nonprofit known as Family Watch International, is one of the two. She is an active organiser in a collective of over 150 ultraconservative campaigners in Uganda, who convene and strategise in a private WhatsApp group.

The deputy speaker of Uganda’s Parliament, Thomas Tayebwa, has called the group “my ideological home”. It was in this group, on 25 January this year, that he wrote: “I think the ground is now ripe to re-table the anti-homosexuality bill.”

By 23 March, the bill had been fast tracked and passed through Parliament.

It was then sent to President Yoweri Museveni, who met with Slater, who lobbied for an exemption clause for LGBTIQ+ people who are subjected to conversion therapy – a set of discredited practices that attempt to change a person’s sexual orientation. The tweaks that Museveni sent back to Parliament mentioned that he considered the idea but dropped it because it would cost the government money.

A 2020 investigation by openDemocracy found that Family Watch International had, for a decade, been coaching high-ranking African politicians, and religious and civic leaders to oppose comprehensive sexuality education across the continent. In the WhatsApp group, Slater messages Ugandan legislators to urge them to lobby for Uganda to oppose UN resolutions that include LGBTIQ+ inclusive language.

Family Watch International told US website Fronteras that it does not support the final version of the Uganda bill. Slater told openDemocracy that aspects of the story put to her were “either false or misleading or both” but that she needed more time to explain why.

Another US citizen, Tim Kruetter, who represents the US-registered Fellowship Foundation in Uganda, is an active player in an influential group called the “National Prayer Breakfast”, which has been described in the US and abroad as an incubator for ultraconservative agendas. Fox Odoi, the only MP to vote against the bill on Tuesday, said in an interview that in Uganda, the prayer breakfast was “the initial entry point” for people who “introduced that ideology of hate”.

The ideology came with money, with Odoi pointing to fellowships in expensive hotels, attended by elected officials, and trips for them to places like Jerusalem.

Kruetter told openDemocracy that he has served as a link to help Ugandans attend the National Prayer Breakfast in the US, but that “the story that I am somehow behind the recent bill in Uganda’s Parliament is false” and added: “I do not speak on the topic of homosexuality.”

Ugandan politician David Bahati has cited US prayer breakfast figures as the inspiration for a similarly harsh antigay bill he drafted in 2009. Parliament passed that bill in late 2013; Uganda’s Constitutional Court annulled it in early 2014, but it formed the basis for the amended bill tabled this year. Frank Mugisha, a Ugandan rights campaigner and head of Sexual Minorities Uganda, a local LGBTIQ+ group, said: “The US government has done nothing to stop its citizens from exporting hate.”

Asked about this, the US government sent a statement, which ignored the involvement of American individuals and nonprofits. Instead, it said the bill would “deter” foreign investors, companies and tourists. A US government HIV/Aids initiative, which gives Uganda about $400-million in aid a year, has indefinitely deferred planning for activities in the country beyond 2023.

The bill will now be sent back to Museveni to either sign into force or to veto – but, if he sends it back to Parliament again, a two-thirds majority of the legislators are constitutionally empowered to override his decision and pass the law without his assent.