Curated by Shola Lawal. Art direction by Wynona Mutisi

The Museum of Stolen History is a new series by The Continent that tells the stories of some of Africa's most significant artefacts.

In July 1799, French soldiers seized control of Rashid, a port town in Egypt. The French call it Rosetta. One of the first things they did was to rebuild the town’s old fort. That’s when they found it, in the construction rubble: a large fragment of stone inscribed with writing in three different scripts.

This stone, known now as the Rosetta Stone, was the key to deciphering Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics – and, in so doing, unlocked the lost history of that civilisation.

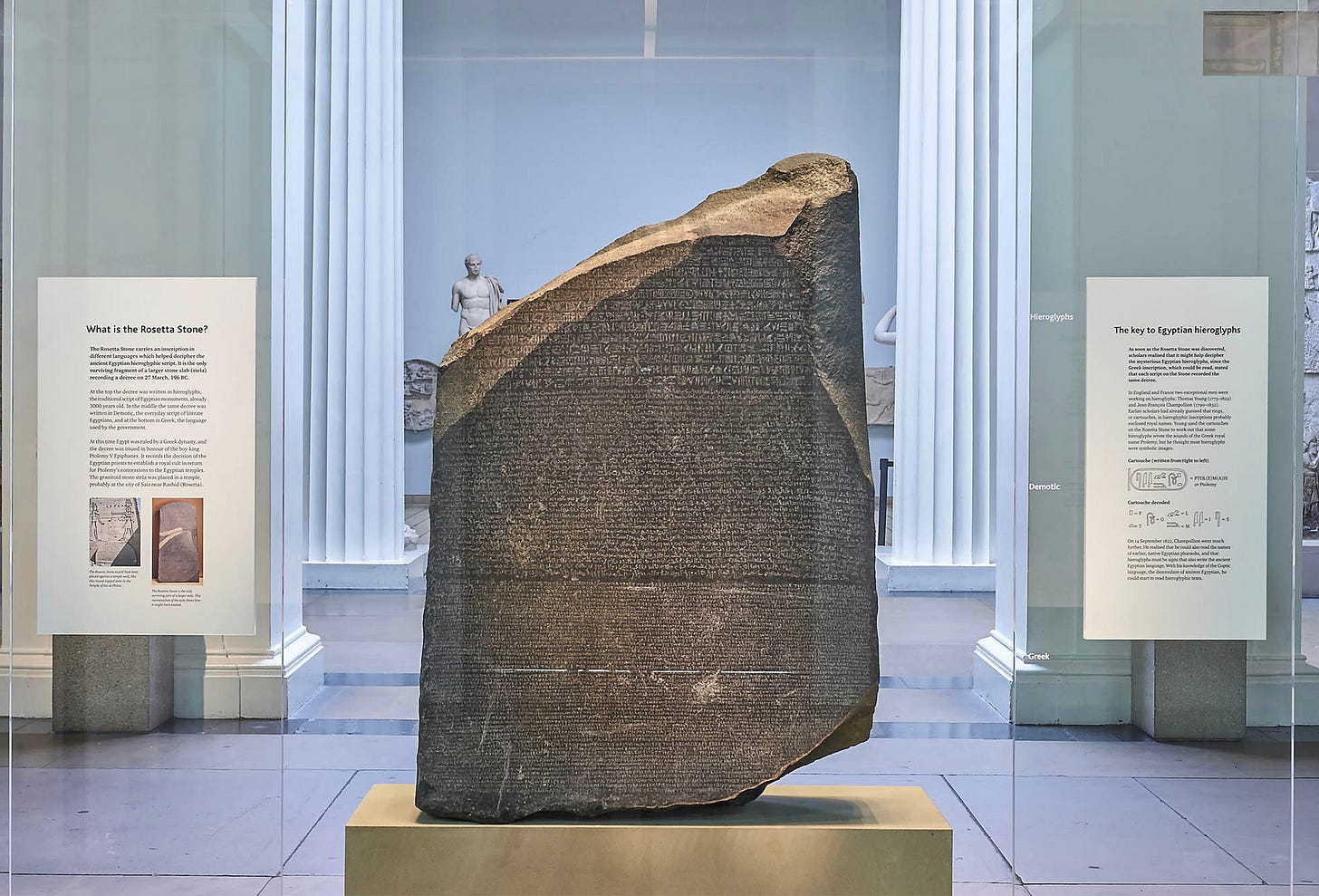

The dark, granite-like slab is a fragment of a larger stele – a standing inscription stone, about 2m tall, used to document written information. This one was a copy of a Royal Decree, issued on 27 March in 196 BCE. The decree commemorates the coronation of a new pharoah, Ptolemy V, and raises him to the status of the gods. It exalts the new pharoah – a boy of just 13 years – as “the mighty one of twofold strength, the establisher of the Two Lands”.

Crucially, the decree is written in three different scripts: hieroglyphics, Ancient Greek, and Demotic. Linguists’ knowledge of Ancient Greek allowed them to translate the 14 lines of hieroglyphics that were legible on the stone. This was the key breakthrough in the development of a hieroglyphics dictionary, which allowed historians to read the text on countless other artefacts from Ancient Egypt.

Even when the Rosetta Stone was inscribed, more than 2,000 years ago, hieroglyphics was a dying script. Only priests used it and then only for official decrees. Greek had become the administrative language. Hieroglyphics is unlike most modern scripts in that it uses a combination of images rather than letters to represent meaning. For example, 𓅓𓂝 means “in the hand of”, and 𓅓𓐟𓏤 means “at the back of”.

When British troops displaced the French in Egypt, they took the artefacts too. The British Museum received the Rosetta Stone in 1802, where it has since become its most-visited object. Weighing 760kg – equivalent to about six baby elephants – the slab was so heavy that the museum’s grounds could not bear the weight, and special structures were built to house it.

Twenty-eight more copies of the stele with nearly the same version of the decree have since been discovered.

Egyptian government officials and individuals have campaigned for years for the return of what they call the Rashid Stone, but without success. The United Kingdom claims it owns it under agreements signed by France and the Ottomans and that Egypt has other copies.

However, renowned archaeologist and former antiquities minister Zahi Hawass tells The Continent that the Rashid Stone is the icon of the Egyptian civilisation and, thus, should be displayed at the new Grand Museum in Cairo.

Among the histories the Rashid Stone unlocked is that of Ptolemy V himself. The pharaoh was an aggressive ruler, conquering territory that had been previously lost by the Ptolemaic Empire. He was also celebrated for lowering taxes. But it is his tragic backstory that has captivated historians.

Both of his parents died when he was five: his father, Ptolemy IV, in a palace fire; his mother in mysterious circumstances. He first ruled with the help of guardians, before being crowned when he turned 13 and came of age. It was then that the decree on the Rashid Stone was issued – and, because it was literally written in stone, we are still talking about it today.