Curated by Shola Lawal | Art direction by Wynona Mutisi

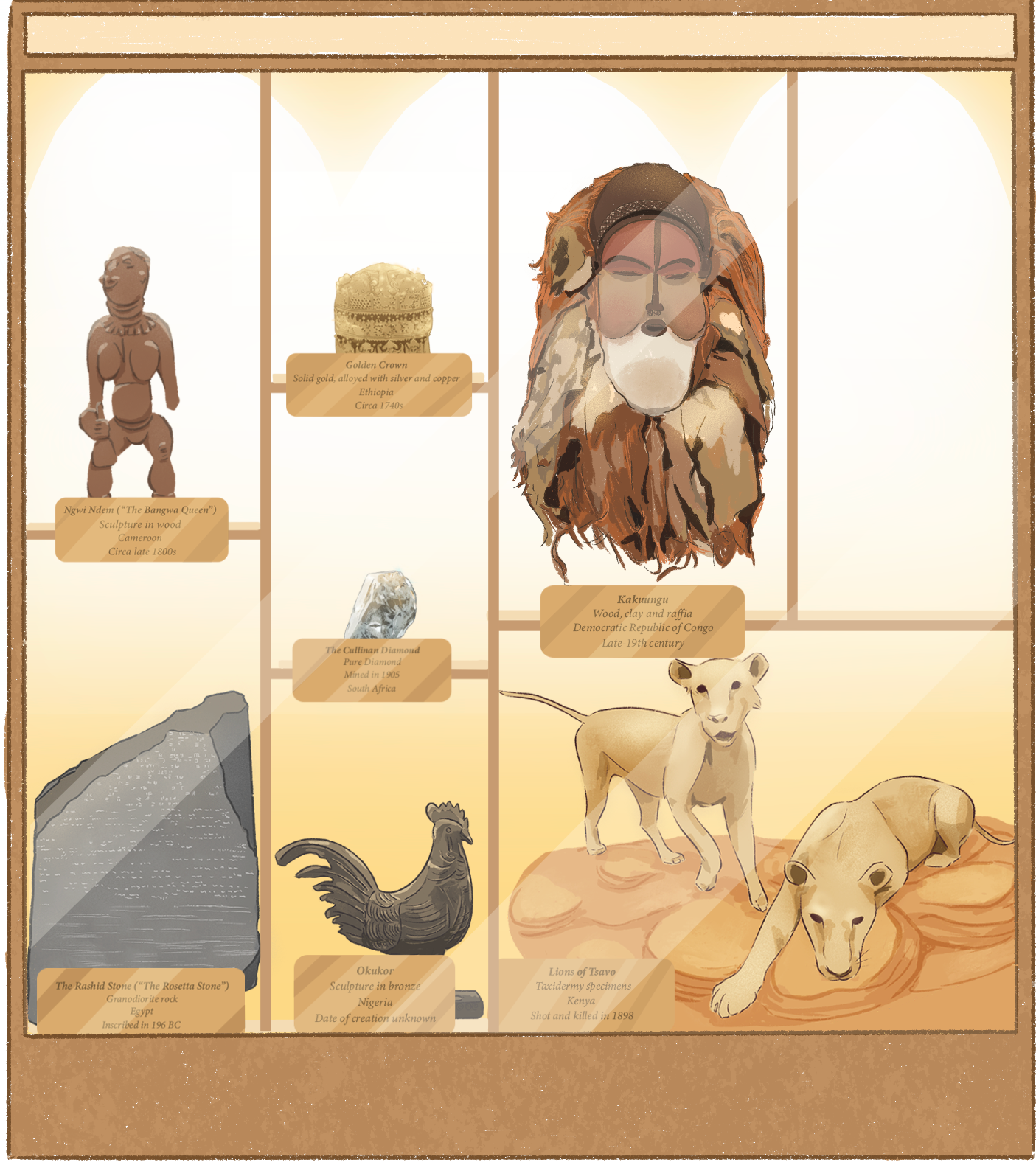

The Museum of Stolen History is a new series by The Continent that tells the stories of some of Africa's most significant artefacts.

If its puffed cheeks, exaggerated chin, and pouted lips provoke instant fear in the observer, then the Kakuungu mask is doing exactly what it is meant to do.

The rare artefact, made of wood, raffia, and tortoise shell, was one of hundreds of items bought by ethnographist Albert Maesen for only a few dollars on behalf of Belgium’s Royal Museum of Central Africa. The mask is 1.5m tall and weighs about 10kg. There are about nine other such masks – and none remains in the Democratic Republic of Congo. This reflects just how intensely that country’s heritage has been looted and hoarded.

Kakuungu, originally a dance mask from the Suku people in the southwestern Kwango region, was worn during rituals to initiate boys into manhood. Its fierce appearance was meant to instil fear, obedience and respect, and ward off threats to initiates. After the rituals, the boys would take new names to mark their adulthood. The Suku believe the mask can cure sterility, calm the weather, and intervene in times of crisis.

Formerly known as the Congo Free State, the DRC suffered through one of the most brutal colonial regimes. Belgian officers coerced local chiefs to sign away their territories in return for alcohol or a piece of cloth. These territories were then claimed in 1885 by Belgium’s King Leopold as his personal fiefdom.

Leopold’s enforcers made locals work on rubber plantations for long hours to fuel Europe’s car and bicycle industry. Punishment for failing to meet quotas or for resisting was severe: severed limbs, or worse, death. Leopold never visited, but the limbs were often set out for his commissioners’ viewing pleasure on trips to the domain. Some 10-million people died. Congo became one of the most lucrative occupation projects.

By the late 1880s, word of the atrocities began to filter out, thanks to missionaries visiting the colony. Journalists and activists from fellow colonial European nations began protesting Leopold’s brutality in newspapers. They denounced “red rubber”, stained with the blood of the Congolese. The king denied any knowledge of the violations. Eventually, the outcry was so great Leopold was forced to hand the region over to the Belgian government in 1908, officially making it a colony.

But conditions remained dire. The Belgian Congo was highly segregated, with locals and Europeans living separately. A deliberate policy of under-education was enforced. Nearly no Congolese people reached university level, and they were never allowed to participate in politics.

Resistance grew, particularly in rural regions where people worked on plantations for little pay. In 1931, in the Kwango district where Kakuungu originated, workers revolted against the colonial authorities and refused to pay taxes. The Belgian army took about 500 lives in the crackdown that followed.

When a wave of independence movements swept across Africa in the late 1950s, Belgium too was forced to hand over the country to the Congolese. But there were fewer than 20 university graduates in the country. There was not a single doctor, lawyer, or Congolese army member. It was going to be a fragile independence. The impacts of this fragility are still evident in the country’s instability today, the Catholic University of the DRC’s Albert Malukisa told The Continent.

Belgium is now reckoning with that colonial past. In 2022, Kakuungu was one of the first objects the country “loaned” back to the DRC indefinitely, as part of an ongoing decolonisation project of its museum collections. Belgium’s King Philippe, on a visit to DRC in June 2022, personally handed the mask to President Félix Tshisekedi. It now sits in the National Museum in Kinshasa.