The Museum of Memory: Part VIII

How we choose to remember: The Last Tree of The Ténéré

Curated by Shola Lawal. Art direction by Wynona Mutisi

The Museum of Memory is a limited series by The Continent that tells the stories of some of Africa's most iconic monuments.

A temple in a corner of the open-air museum complex in Niamey houses the frail remains of L’arbre du Ténéré. The tree, an ancient acacia with two curved trunks, is rooted into a cement base and its gnarly branches push towards the temple’s ceilings.

Symbols of the Tuareg people, spread across northern Niger from where L’arbre du Ténéré originates, are inscribed on the blue-and-white temple’s base and front walls.

The tree has spun legends for decades, with some people wondering if it has mystical powers. For about 300 years, the old acacia blossomed alone in a vast area of Niger’s chunk of the Sahara. Its presence was wondrous: a living reminder of the once-green savannah that existed in the desert thousands of years ago, replete with lakes, vegetation and wildlife. This was before a great climate-change event caused the area to dry out and become one of the most arid patches on Earth.

L’arbre du Ténéré was once part of an acacia forest. However, by the 20th century all its neighbours had died off. The sole tree was located halfway on the untarred route that the azalai, or salt-trading caravans, took from northern Agadez to Bilma, the town of large salt mines 400km to the east.

For locals, the acacia was a signpost on their journey. Every year, before they crossed the Ténéré, the azalai would gather under the tree, as though gathering strength from it. Legend has it that the acacia had no neighbours within 400km, although the oasis town of Timia is 150km to the west.

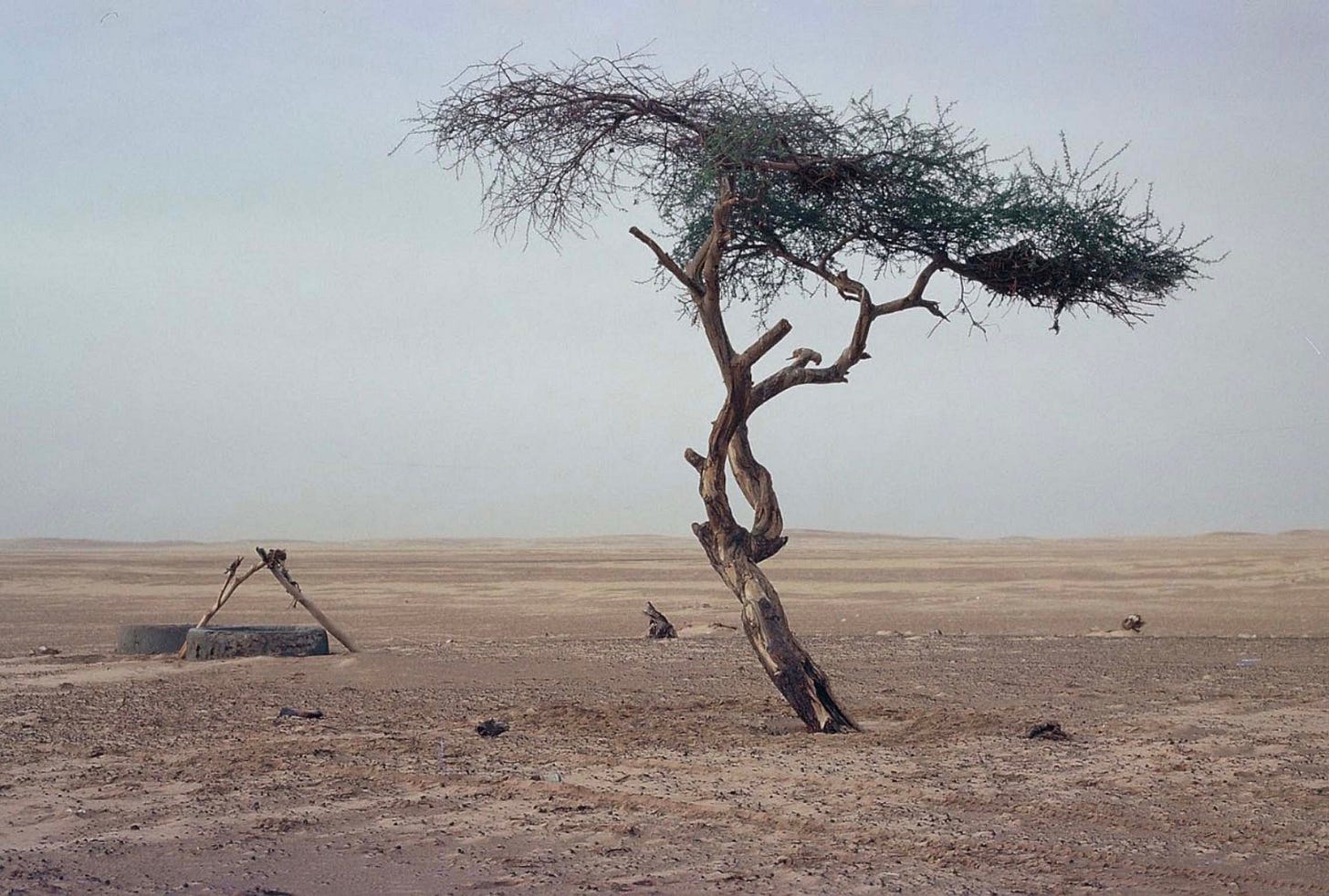

Foreigners were baffled, particularly French explorers who traversed the area when Niger was colonised by France from the 1890s. The patch of the Sahara where the tree stood was known as the Ténéré, or “wastelands” in the local Tamasheq language, and is famed for its harsh landscape – a desert within the desert.

Nothing survives in the blistering sun and the hot blankets of sand. Yet, the acacia stood.

L’arbre du Ténéré was the muse of several French officers. Cartographers marked it on maps as a notable landmark. In his memoir, Michel Lesourd, a French army officer who saw the tree in May 1939, pondered how it survived, why no camels from the travelling caravans had eaten its branches, and why locals were never tempted to cut it down for firewood.

Perhaps it was sacred and touching it was taboo, Lesourd wrote. Later, the officer found some answers: a well dug by the French colonial military close to the tree revealed its roots went at least 30m down to the water table.

There were signs of the tragedy to come. In 1959, French explorer Henri L'hote wrote in his notes that its girth was significantly reduced since he first saw it some decades before. The lower branches were gone and it had lost some leaves at the top. Part of its trunk appeared torn out; he wrote that a vehicle had hit it.

Then, in 1973, a Libyan driver ran his truck straight into the tree, killing it. He was believed to be drunk. The 300-year-old tree was dead.

It was heartbreaking news for Nigeriens. The tree was transported to Agadez by car, before its remains were airlifted to the museum in Niamey, where it remains. In 1974, the Nigerien government issued postage stamps featuring the acacia to commemorate its death.

A metal contraption, made of a pole that’s affixed to tin drums at the base, now stands in the tree’s original spot, a touching attempt to memorialise the lost acacia. Passing tourists often chalk their names on the memorial.