Curated by Shola Lawal. Art direction by Wynona Mutisi

The Museum of Memory is a limited series by The Continent that tells the stories of some of Africa's most iconic monuments.

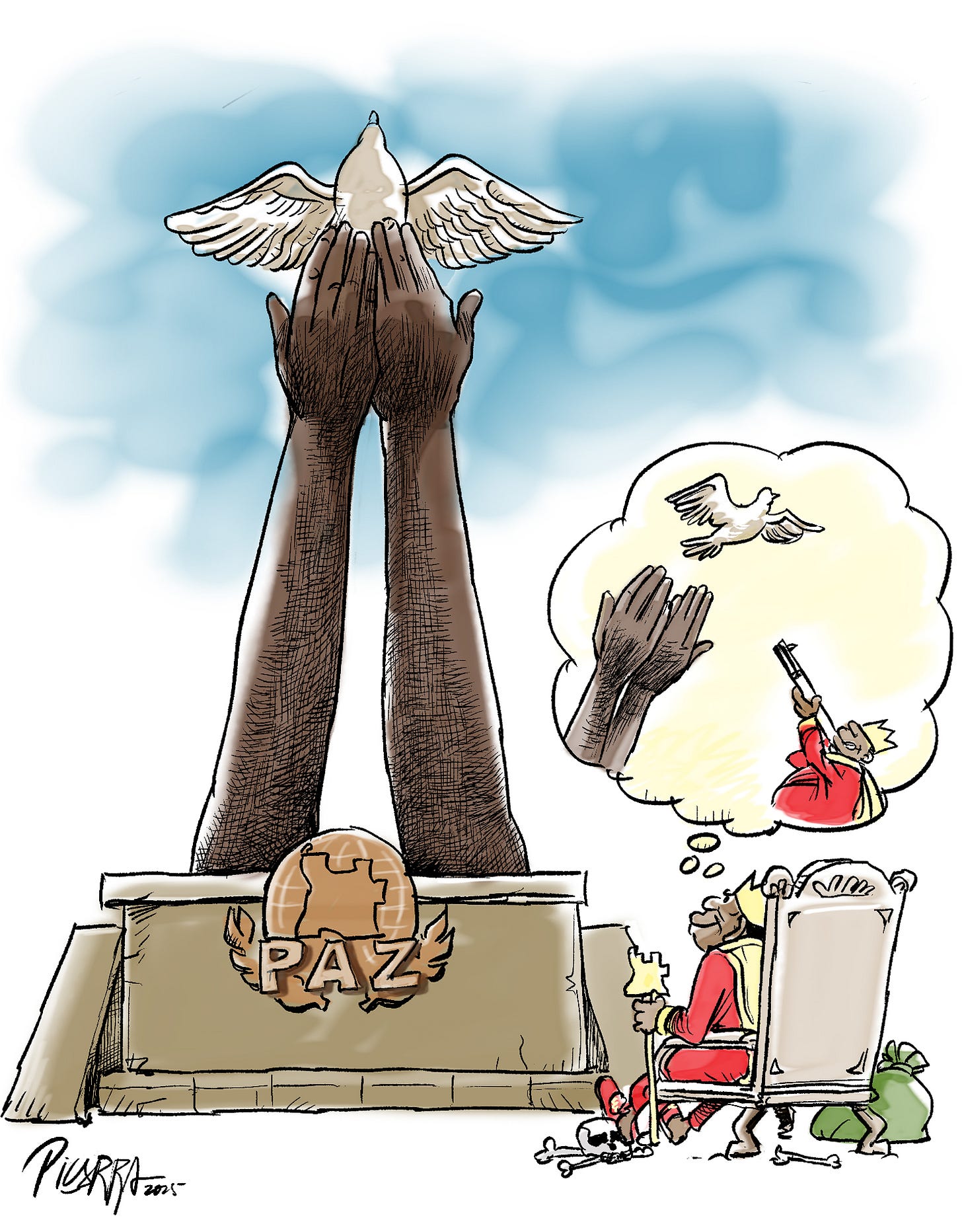

Two giant hands, representing a once-divided country, release a white dove into the sky. Monumento da Paz is meant to evoke Angola’s striving for peace and healing after a brutal 27-year civil war. The 30m-tall structure, made of copper and iron, is located in Luena, the capital of the eastern province of Moxico.

Two construction companies – North Korea’s Mansudae Group and China’s SinoHydro Corporation – jointly developed the monument, as well as the gardens and complex surrounding it. Work began in 2009 and then-president José Eduardo dos Santos unveiled the monument on 4 April 2012.

This date marked the 10th anniversary of the end of the civil war.

During the rainy season, trees and flowers in the large garden that wraps around the monument bloom in bright colours. The buildings flanking the garden house a library and reading room, a restaurant, an amphitheatre, and bookstores. Some areas have fallen into disrepair but authorities say they are planning a large renovation project.

For 13 years, between 1961 and 1974, the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and the National Union for the Total Liberation of Angola (Unita) fought a guerrilla war against the Portuguese colonial army. However, even as the two movements fought for Angola’s independence, they turned on each other in a parallel war. Each group wanted to position itself as the dominant force in the post-independence country. It didn’t help that support for each split along ethnic lines. Unita, led by Jonas Savimbi, was stronger among the Ovimbundu and Bakongo. Support for the MPLA, led by Agostinho Neto, mainly came from the Ambundu and mestiço (mixed race) people.

When Portugal left the country, power was handed to a fragile transitional government comprising Unita, the MPLA and the National Liberation Front of Angola. The Alvor Agreement, named for the Portuguese city in which it was signed, came into effect on 15 January 1975. However, fighting between Unita and the MPLA resumed within months.

Foreign interference dramatically escalated the war, which was playing out during the Cold War between the communist Soviet Union and the United States. In Angola, the Soviet Union and Cuba backed the MPLA, sending thousands of troops and weapons. Unita received military support from apartheid South Africa, which was channelling it from the US. Eventually, the foreign armies withdrew because funding this proxy war proved too costly.

Fragile peace deals between the domestic parties frequently broke down over the years. Both sides massacred civilians as the war descended into its bloodiest phase in the 1990s. It was during this time that Unita’s Savimbi reportedly descended into dictatorship.

People who knew Savimbi described him as skilled in warfare and an excellent orator who spoke multiple languages, including English, although he’d never lived in an anglophone country. Initially, he was something of a peacemaker who pushed for talks and spoke about the need for elections. But then he reportedly began ordering the deaths of his trusted advisers and their families when they expressed dissent.

As officials were either killed off or defected, the Unita army grew weak. In February 2002, Savimbi was killed in battle in Lucusse, Moxico and Unita forces immediately surrendered, ending the war. About 800,000 people were dead, and more than a million were displaced. Angola’s economy was in shambles.

Luena, where the peace accords of 4 April 2002 were signed, was the ideal point to build the peace monument. About 12,000 tourists visit the Monumento da Paz each year. Visitors say that if you stand about 100m to the side of the monument and raise your hands, it will look as if you’re releasing the huge white dove into the sky yourself.

The MPLA continues to dominate the Angolan government – but the country’s politics is still deeply divided along ethno-political lines.

Great article, and bold illustration, thanks to the author and illustrator. It seems that erecting a memorial allows people to forget.