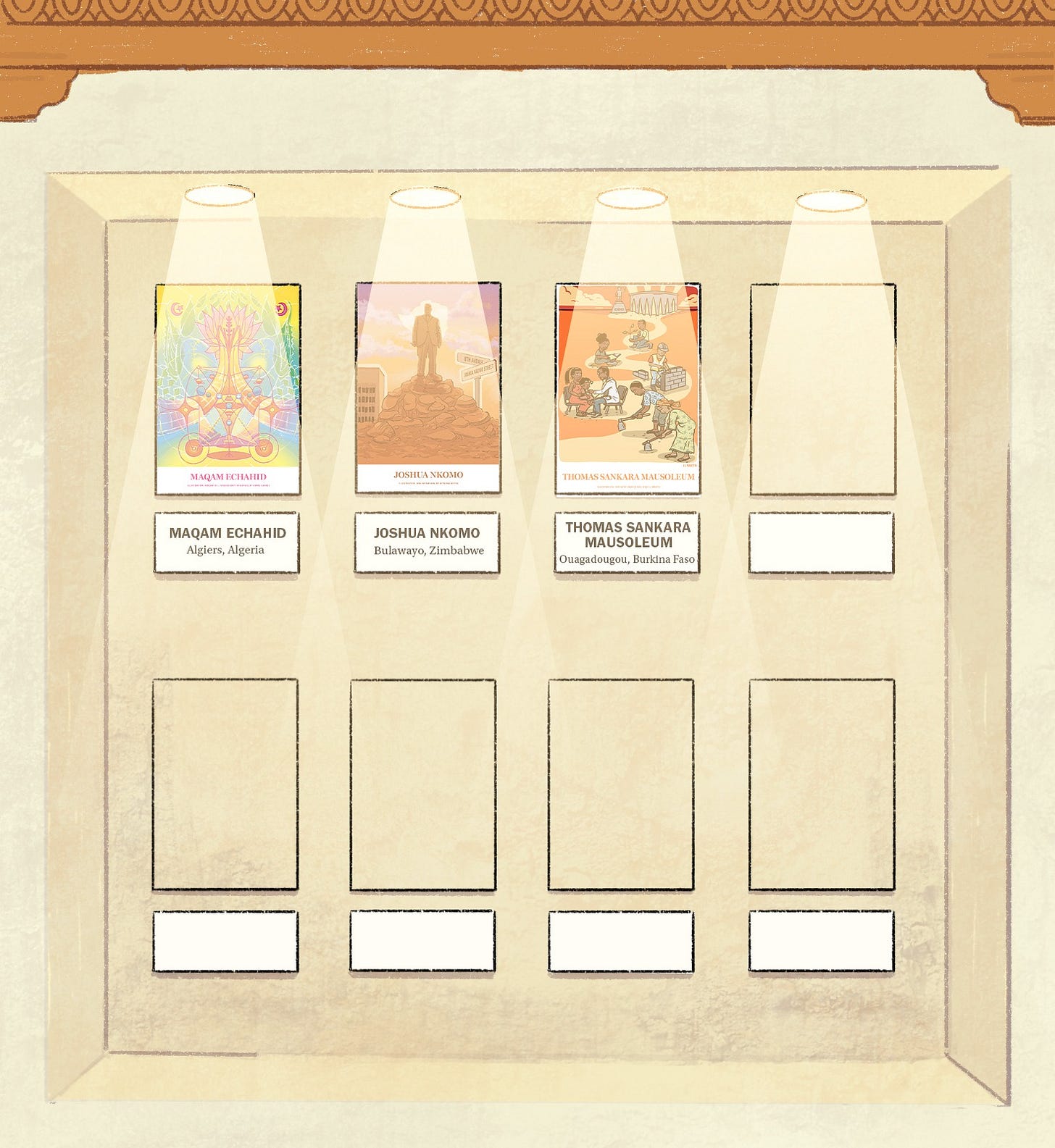

Curated by Shola Lawal. Art direction by Wynona Mutisi

The Museum of Memory is a limited series by The Continent that tells the stories of some of Africa's most iconic monuments.

The Thomas Sankara Mausoleum in Ouagadougou is like a fantasy Wakanda building come to life. Clean lines, V-shaped pillars, earthy colours and local laterite bricks combine in an eye-shaped structure that nods both to indigeneity and cutting-edge science.

Its orange mud bricks are a hallmark of Diébédo Francis Kéré, the Burkinabé architect who designed the building. In 2022, Kéré became the first African to win the Pritzker Architecture Prize.

Commissioned by former president Marc Christian Kaboré, the mausoleum was unveiled in May this year. It’s part of a wider effort to honour the legacy of Burkina Faso’s most famous son: former revolutionary leader Thomas Sankara, who led the country between 1983 and 1987.

At 32, Sankara rose to power after a coup in what was then Upper Volta. During his four years in power, he set out to rid the country of foreign aid and corruption, and foster self-sufficiency.

He shunned the International Monetary Fund and launched agricultural projects to promote local food production. He built schools, railways and roads, distributed vaccines to children across the country, and abolished forced marriages and female circumcision. Then he renamed the country Burkina Faso – the land of upright men – and wrote its national anthem.

Sankara stood out internationally for his charming oration and his bullish stance against the dominant capitalist order. He railed against supporters of apartheid South Africa (including the United States), the oppression of Palestine, and French neocolonialism.

His fiery speeches won over many Burkinabé and Africans in general, who labelled him “Africa’s Che Guevara”. Foreign powers like the US and France – and officers in his own cabinet – were not amused. Sankara made enemies with neighbours, too. Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi and Liberia’s Charles Taylor were rankled by his refusal to let Burkina Faso become an arms corridor between their countries. Côte d’Ivoire’s Félix Houphouët-Boigny, a close ally of France, did not care for him either.

Rights organisations faulted Sankara for prosecuting and detaining dissenters. Aid cuts weakened the country economically, denting local support.

Ultimately, it was factions in his government who would unravel the revolution. Sankara was assassinated, along with 12 others, in a coup led by his friend and deputy Blaise Compaoré on 15 October 1987.

Compaoré ruled for 27 years. His bid to run for president again in 2014 triggered fierce protests across the country. He fled to Côte d’Ivoire and, in absentia, was found guilty of the 1987 assassinations in 2022 and received a life sentence.

Only after his fall could Burkinabés memorialise Sankara properly.

Honouring him in a way that measured up to his legend was difficult. In 2020, Burkinabé artist Jean-Luc Bambara was forced to rework his 2019 bronze sculpture of the icon. Burkinabés had criticised the figure for bearing no resemblance to their beloved Sankara. Bambara said high temperatures in the Sahelian country had melted the cast.

The mausoleum was built near that statue and marks Sankara’s final resting place. Inside, his marble tomb is flanked by the smaller tombs of his 12 slain companions. The structures are arranged in an arc, inspired by the sun’s path as it rises. Over each tomb a small opening allows in light during the day and seems to extend the skies right down to the concrete casings. At night, the same openings allow light to escape from the hall, making it visible from outside.

An ambitious memorial complex, also by Kéré, will surround the mausoleum. It will include an amphitheatre, teaching facilities and a 100m-tall tower. Kéré, speaking to The Guardian, said the mausoleum would not only mark the tragedy, but would also be a space for Burkinabés to partake in joyful activities, from studying to holding weddings.