The African Union’s moment of truth

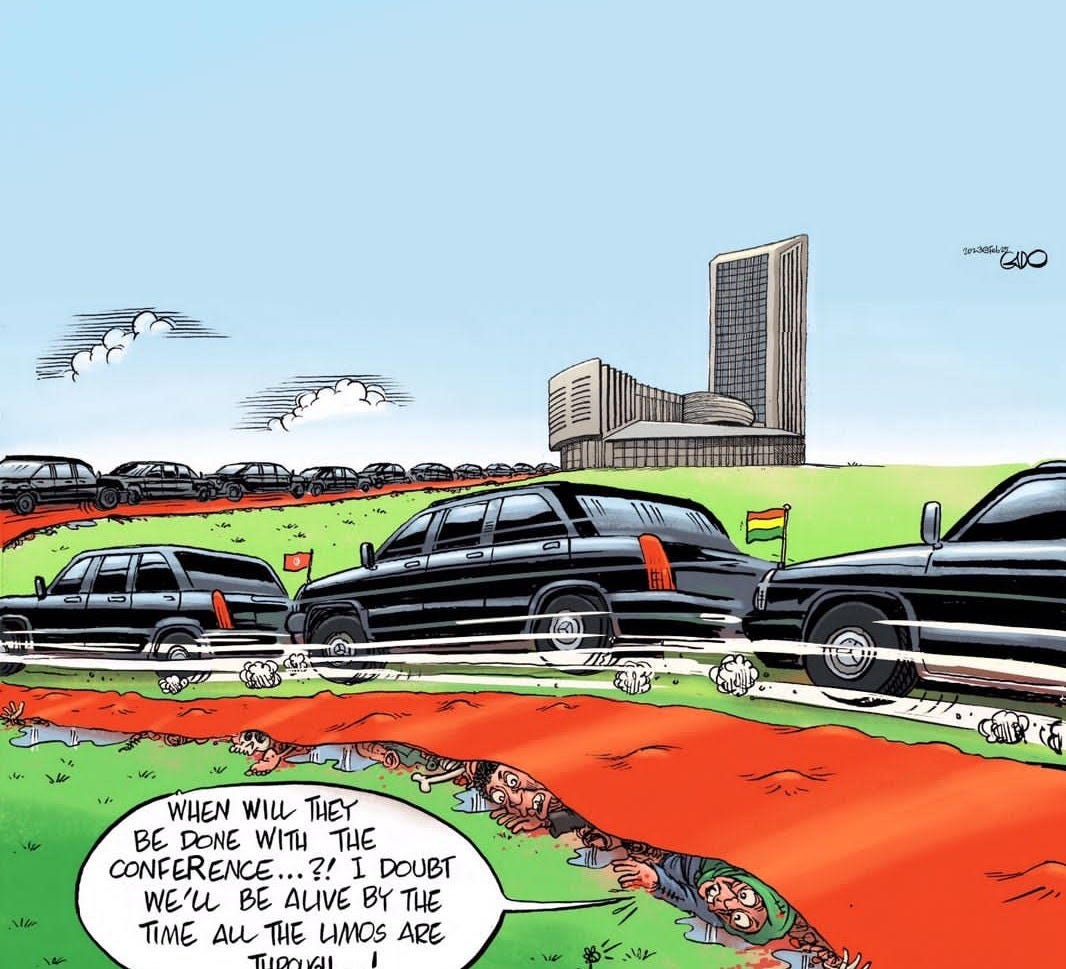

At this weekend’s summit in Addis Ababa, our presidents must decide: Does the continental body serve them, or us?

Simon Allison

In March 1990, the Tanzanian statesman Salim Ahmed Salim visited Muammar Gaddafi in Tripoli. At the time, Salim was just six months into his long tenure as secretary-general of the Organisation of African Unity. According to Salim’s notes, the Libyan dictator made him wait before eventually granting him an audience in the ruins of a former presidential compound that had been bombed by US warplanes several years earlier. Gaddafi had turned the compound into a museum.

On two chairs set up outside a tent, the pair discussed the major issues of the day – civil war in Ethiopia; clashes in Darfur; the Western Sahara dispute before Gaddafi steered the conversation towards global geopolitics. The Cold War was over and the Soviet Union was collapsing. Suddenly, the world was a very different place. The sense of change, and possibility, was tangible.

So too was the threat. “I think the map of the world will be reshaped,” said Gaddafi. “I am afraid, and I am sorry for it, Africa will have its part.”

Both Gaddafi and Salim went on to play a key role in the creation, in 2001, of the African Union – Africa’s attempt to respond to this new world order. The new institution was better-structured, better-resourced and more empowered than its predecessor. The thinking of its architects was simple: we are stronger together. Without a strong continental body, Africans will always be at the mercy of foreign powers.

More than three decades later, the world is being reshaped again. Africa will have its part – and there is plenty of cause to be afraid.

Already, in just a single month, the impact of an isolationist and explicitly racist administration in the United States is being felt on the continent. Billions of dollars in development assistance have been withdrawn; the lives of millions of Africans are imperiled by the halt in distribution of key medication; and President Donald Trump has threatened a trade war against South Africa, the continent’s largest economy. Meanwhile, right-wing movements like Trump’s are gaining ground all over the western world, while international institutions like the United Nations and the World Health Organisation are getting weaker.

The threats loom large. So too do the possibilities.

How the AU responds may determine the economic and political future of this continent for generations to come.

Now is its moment of truth.

Tectonic shifts

For the AU, the timing of all this global upheaval is interesting.

The chair of the AU Commission, Moussa Faki Mahamat, is nearing the end of his second four-year term and is not allowed to run for the position again. That’s just as well: assessments of Faki’s tenure are uniformly damning – pointing to chronic mismanagement, widespread corruption and cronyism, and a timid, ineffective approach to conflict prevention (see: Sudan, the Sahel, Ethiopia). Last week, in Dar es Salaam, Faki endured the ultimate humiliation. At the regional meeting called to discuss the conflict in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, Faki was ordered out of the room before the talks got serious. Even his peers do not trust him with sensitive negotiations.

This weekend, at the AU headquarters in Addis Ababa, heads of state will gather to elect Faki’s replacement. The three candidates are Mahmoud Ali Youssouf, the foreign minister of Djibouti; Raila Odinga, the former prime minister of Kenya; and Richard Randriamandrato, the former foreign minister of Madagascar. But whatever Faki’s own faults were, there are structural issues that make it difficult for the AU chair to exert authority. Whoever wins will face them as much as Faki did.

One issue is that the chair answers to, and implements the decisions of, the African Union Assembly – composed of the heads of the 55 member states. Given the governance records of too many of those heads of state, it is hardly a surprise that issues like corruption and due process are not taken seriously.

Another issue, perhaps even more significant, is that these member states do not provide nearly enough funds for the AU to operate effectively. In fact, the contributions of member states account for only a third of the AU’s budget. Other countries – international partners in AU terminology – make up almost all the rest: $370-million of last year’s $605-million budget. The AU was intended to help Africa assert its independence from foreign powers. Instead, it is almost entirely beholden to them.

Now or never

Fortunately for whoever succeeds Faki, if they try to remake the AU, they will not be doing it alone. In 2018, 37 women staffers within the African Union Commission wrote a letter to Faki.

The letter described a “professional apartheid” within the AUC, in which women were routinely discriminated against for promotion and opportunities.

It was leaked to the Mail & Guardian, which published a related investigation in May of that year, causing a furore within the institution. The resulting media attention forced the AUC to appoint an independent commission of inquiry. This inquiry, led by the Senegalese feminist advocate Benita Diop, upheld the complaints in the original letter. But it went even further, concluding that sexual harassment, fraud, nepotism and abuse of power was rife within the institution. The report named names – although these were never revealed publicly. No further action was taken against the alleged perpetrators, and the commission was later accused by staffers of covering up the allegations.

That effort at accountability, triggered and ultimately defeated by the worst of the AU, nonetheless revealed its best potential. It showed it as an institution with people who, despite it all, are willing to risk everything and stand up to the combined power of 55 heads of state in the service of good governance and pan-African values. If Faki’s replacement can harness this spirit and courage, the AU might come to fulfil the destiny envisioned by its founders.

It is possible. Take the example of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, which steered the continent through a global pandemic. Or the ratification of the African Continental Free Trade Area: critics said it was unachievable, until it happened – pushed through in large part thanks to the relentless energy of the AU trade commission.

As the global order disintegrates, the emerging multiple poles of power are jostling for influence in this continent. What bargains they strike will either be driven by a united voice coming out of the AU, or by the disparate interests of 55 states and various blocs.

Which it will be – divided and ruled, or a continent united – depends largely on the gravitas and capabilities of the man who wins the AU election this weekend. It also depends on the African public’s engagement with the institution. And on whether people rally behind those who seek and deliver its wins, or those who use it for their own ends.