Tanzania is at a dangerous crossroads

President Samia promised to chart a more democratic course for the country. It’s not too late to make good on her vow, but the red flags are getting redder.

Deus Valentine

Last month, all of Tanzania’s major political parties held rallies to commemorate International Youth Day. There was one major exception: Chadema, the largest opposition party, had planned a big rally in Mbeya, a city in the south-west of the country.

But it never happened.

Shortly before the event was scheduled to take place, it was banned by Tanzanian police, who said the rally was likely to trigger violent protests. Commissioner Awadh Juma Haji said police would do everything in their power to resist such “glaring threats to public order”. In particular, Haji took issue with a statement by a Chadema youth leader which called for opposition supporters to be “inspired by our colleagues in Kenya”.

In Kenya, months of widespread protests – driven by young Kenyans, and organized via social media – piled pressure on President William Ruto. A brutal response by state security forces, which killed dozens, failed to quell the unrest. Eventually, Ruto fired his entire cabinet and was forced to halt planned tax hikes.

Wary of similar scenes playing out on the streets of Dar es Salaam, Zanzibar and Mbeya, Tanzania’s authorities banned the Chadema rally and arrested more than 500 young Chadema supporters as they attempted to gather in defiance of the ban.

The police also roughed up senior Chadema leaders – including secretary-general John Mnyika, national vicechairman Tundu Lissu and central committee member Joseph Mbilinyi – and then detained them for 48 hours.

The scenes were reminiscent of the violent authoritarianism that characterised the presidency of the late John Magufuli, who died in office in 2021. In those dark days for Tanzania’s democracy, opposition parties were forbidden from holding rallies by presidential decree, and their leaders faced both judicial and physical persecution. Tundu Lissu, for example, only narrowly survived an attempt on his life in which he was shot 16 times.

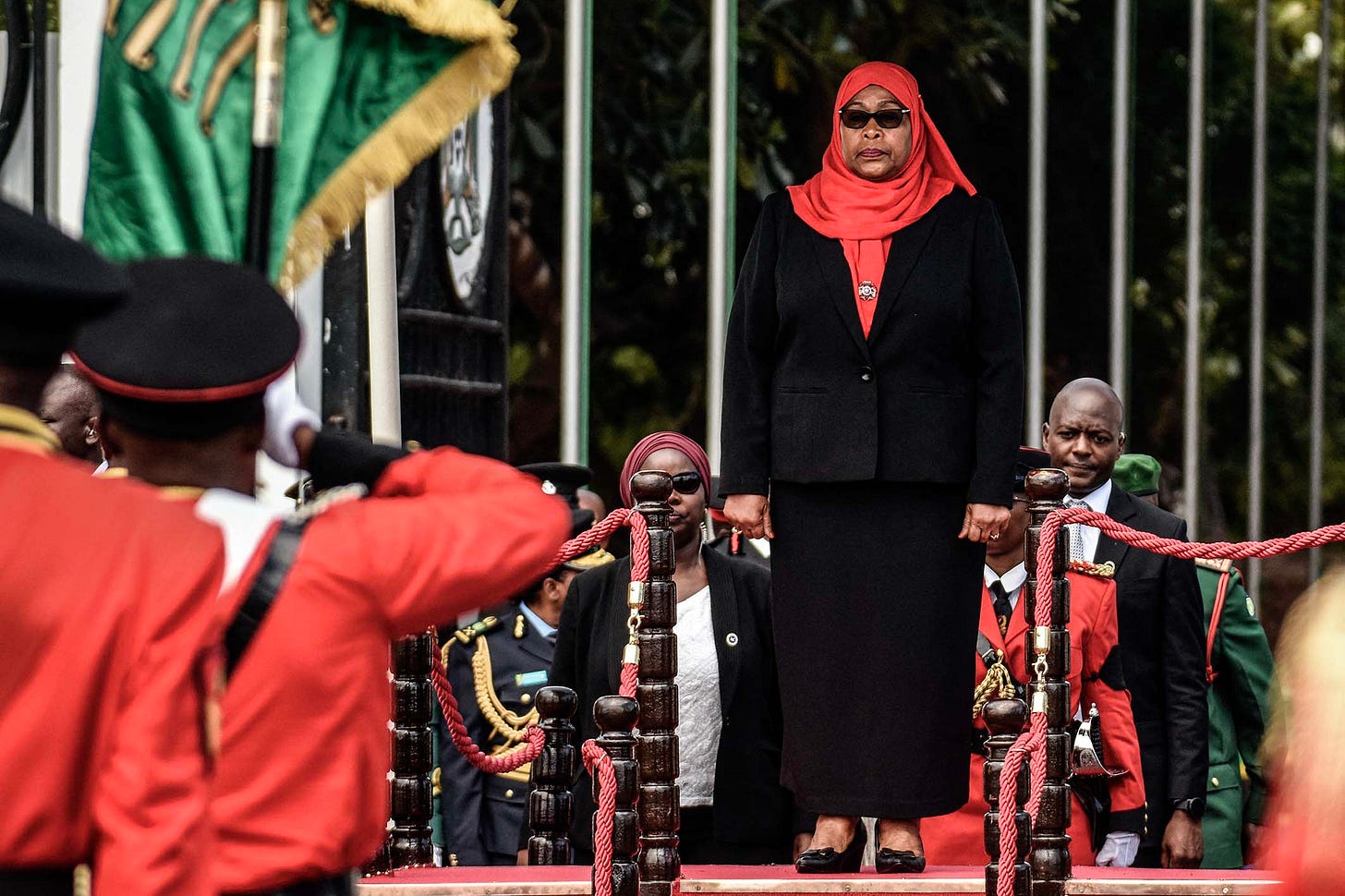

Magufuli’s successor, President Samia Suluhu Hassan, initially promised to be different. She has allowed independent news outlets to operate, and, in January 2023, she reversed the presidential ban on opposition rallies. This meant that other political parties could campaign freely for the first time since 2016. She has been praised by business leaders for creating a better climate for international investment, and has pursued a sciencebased public health policy – a far cry from Magufuli’s infamous and deadly Covid denialiasm. On her watch, commissions on criminal justice and democratic reform outlined potential fixes for the foundations of Tanzania’s democracy, although neither has yet led to any concrete change.

“Certainly, Tanzania is less sinister and less mad since she took over,” observed The Economist earlier this year.

Bad habits

But with local elections happening in November, and presidential elections planned for next year, President Samia’s administration appears to be reverting to some of her predecessor’s bad habits, of which the banned Chadema rally is just the latest example.

Another is the recent call, made by Zanzibar’s police commissioner Hamad Khamis Hamad, to effectively censor political speeches. He said the police would review every speech made during political rallies, with the aim of identifying utterances made against the state, or aiming to incite hatred.

These comments appear to be directed towards ACT-Wazalendo, another major opposition party, which has used its rallies to make serious allegations of corruption and electoral fraud against the ruling party, Chama Cha Mapinduzi (the party denies these allegations).

An even more ominous trend is that opposition figures keep disappearing.

In July, regional police in Tanga confirmed that they were holding Kombo Mbwana, a Chadema district leader – some 30 days after Mbwana went missing. He has not been presented before court, despite appeals by his lawyers.

Two other Chadema leaders – Dioniz Kipanya from Rukwa and Deusdedith Soka from Temeke in Dar es Salaam – have also gone missing in the past month, with no word from authorities.

Last month, the Tanganyika Law Society released a list of 83 people, including Mbwana and Kipanya, who have disappeared recently under mysterious circumstances.

“The police have repeatedly denied the occurrence of such incidents, only for it to later be revealed that the incidents were indeed true. In some cases, the police have even arrested good citizens who reported these incidents, accusing them of spreading false information,” the law society said.

Dangerous direction

Taken together, these incidents show that President Samia’s government is heading in a troubling direction – a direction that is all too familiar to Tanzanians who lived through Magufuli’s regime. This perception is not helped by the return of some key Magufuli allies – initially sidelined by President Samia – to key positions in government.

The most egregious example of this is Paul Makonda, the former Dar es Salaam commissioner who gained global notoriety when he formed a task force to arrest members of the capital city’s LBTQIA+ community. After spending three years out of political office, the president appointed him to lead the country’s third-largest city, Arusha, earlier this year.

The warning signs are clear. Nonetheless, it is not too late for the president to make good on her initial promise. Halting the disappearances, and holding someone accountable for them, is a good place to start.

But the real test of her commitment to change is whether she is willing to actually implement the reforms recommended by the commissions on criminal justice reform and democratic reform – commissions that she herself initiated. These reforms would introduce safeguards to prevent the abuse of power by government officials, and would introduce sweeping changes to make the country’s electoral system more fair.

The reforms would make President Samia unpopular within the ruling party – after all, the existing electoral system has kept it in power since independence in 1961. But if implemented, they would secure her legacy as one of the most consequential presidents in this country’s history. The country’s democratic future may hinge on whether she chooses to go down this route, instead of following in her predecessor’s footsteps down a much more dangerous path.