Taboo artists: The fading of Egypt’s healing ink

Along the Nile Valley in Upper Egypt, tattooing became common in the early 20th century

Yasmin Shabana

Seventy years ago, in August, 12-year-old Nema Ahmed and her family visited the Monastery of the Virgin Mary in the mountain village of Dronka in Assiut, Upper Egypt. It was there, at the urging of the older women in her community, that Ahmed had a tattoo – a daq as it is called in Arabic – etched onto her left wrist. The purpose was not aesthetic but therapeutic.

She had been suffering from carpal tunnel syndrome for more than five years.

“Miraculously, after she got the tattoo, the pain disappeared and rarely returned,” said her granddaughter, Mona Fathy.

Along the Nile Valley in Upper Egypt, tattooing became common in the early 20th century, primarily among women.

These tattoos were both decorative and, at times, believed to have healing properties. The most popular tattoo designs of the time featured three evenly spaced lines, a circular dot at the end of the chin, and bracelet-like patterns on the hands.

According to the Egyptian Archive for Folklore and Popular Traditions, tattoos were historically used to signify class distinction, tribal affiliation, or social status. The practice was common in rural areas in northern and southern Egypt and among Bedouin communities.

When tattoos were employed for therapeutic purposes, short lines or dots were inked on the sides of the head to alleviate headaches or on the back of the hand to relieve pain in the fingers and hands.

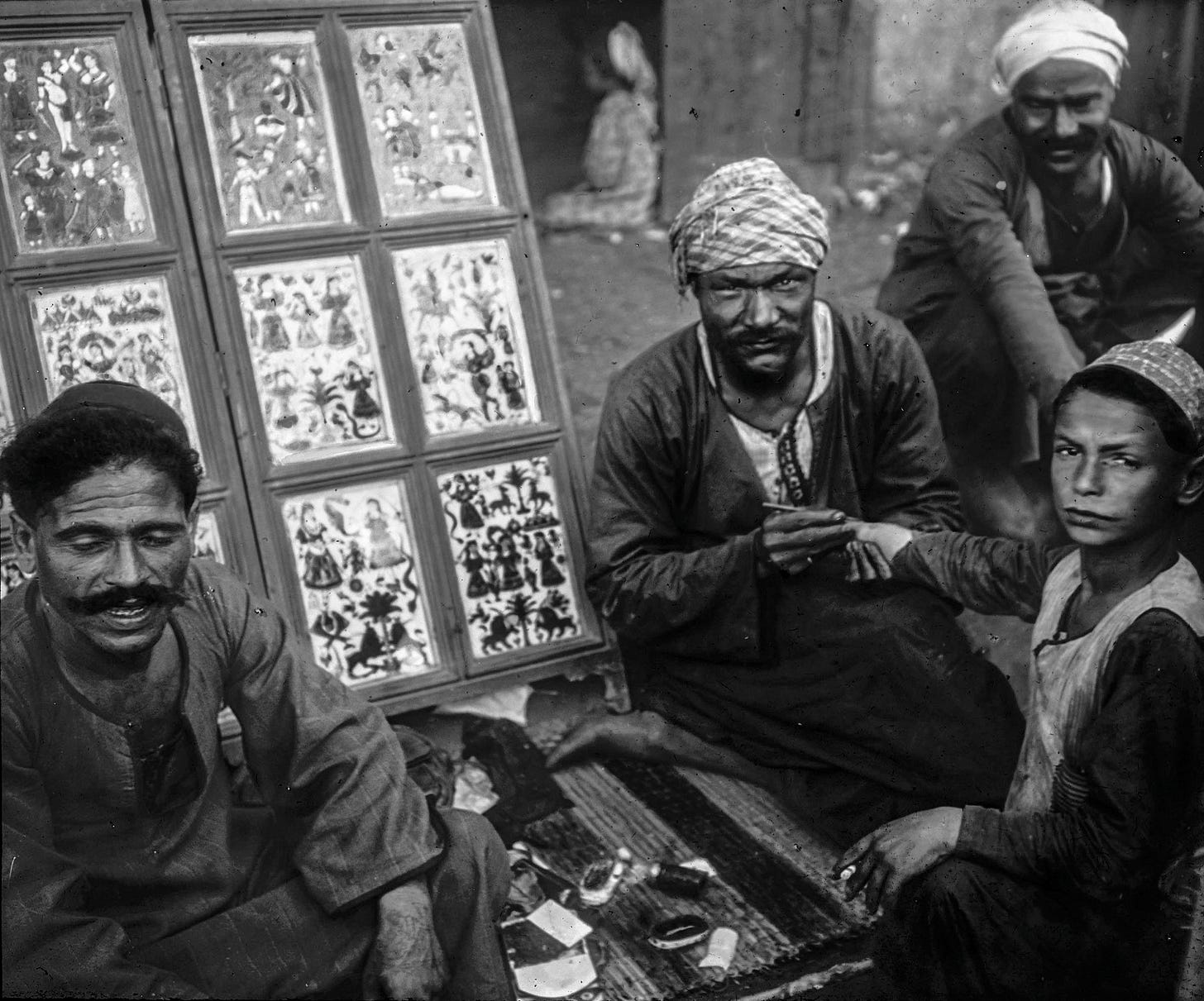

Typically, a local female expert performed the tattoos, travelling from village to village and summoning women with her calls. In her book, The Fellahin of Upper Egypt, English anthropologist Winifred Blackman described how tattoo specialists displayed various designs in the village market, the most popular of which was a tree. Her tools were simple: needles attached to a short stick, the end wrapped with thread. Soot from gas lamps was often used for ink.

As the years passed and religious conservatism – particularly Salafi-Wahabi influences – spread throughout the region, the tradition of tattooing gradually faded. It is viewed as incompatible with stricter interpretations of Islam.

For many in Upper Egypt today, daq is a relic of a bygone era, a once-vibrant tradition now consigned to memory.

“These were our customs and traditions. Our hearts and intentions were pure, and our reckoning is with God.”

According to Khalil Manon, an anthropologist, the infiltration of Wahhabi thought into Egypt began in earnest during the mid-1970s, when the late president Anwar Sadat launched his Open-Door Policy after the October 1973 war.

This period also saw an exodus of Egyptians to the Gulf states, particularly Saudi Arabia. They returned bringing with them conservative religious ideologies that had taken root in the Gulf. These ideas, including stricter interpretations of Islamic teachings, began to permeate Egyptian society, influencing social norms and practices.

The pressure to conform to these new standards grew, particularly in rural areas, where traditional customs began to be viewed through a more religiously conservative lens.

With the rise of these religious edicts, some people attempted to convince Fathy’s grandmother to remove her tattoos, but she refused. According to Fathy, her grandmother would say: “These were our customs and traditions. Our hearts and intentions were pure, and our reckoning is with God, who knows our true intentions.”

Today, the practice of tattooing has all but disappeared from the villages of Upper Egypt. The only traces that remain are on the bodies of the elderly women, or in old family photographs.

In 2003, Fathy’s grandmother suffered from another carpal tunnel episode, this time in her right hand. Fathy recalls how her grandmother was eager to get another tattoo, just as she had done decades earlier to relieve the pain.

“We tried to find the tattoo artists – who were often Romani women that could be found at religious festivals – but we couldn’t locate anyone in the Upper Egyptian villages where we asked,” she said.