Rahiem Shadad

Oslo-based Norwegian-Sudanese artist Khalid Shatta watches from afar as war deepens Sudan’s divides. “This conflict has polarised communities and reignited questions about ‘What is Sudan?’ and ‘Who is Sudanese?’”

For Shatta, these are not abstract questions – they have shaped his life.

Shatta grew up in Khartoum Bahri, the northern city in Sudan’s tri-city capital. But he was born in 1989 in the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan, more than 500km southwest of Khartoum.

“I remember being about 10 years old and asking my mother if I was Wad Arab or Wad Afriki – an Arab’s son or an African’s son. She looked at me and said, ‘Khalid, with a nose like yours, no one could ever mistake you for an Arab.’”

This sharp identity divide between “Arab” and “African” Sudanese stems partly from colonial policy. In 1922 the British introduced the Closed Districts Law, restricting movement and exchange between Arab-controlled regions in the north, central, and east and “African” regions in the south, southeast, and west. It reinforced ethnic divisions despite many communities being multi-ethnic. British-spurred development concentrated economic and educational opportunities in Khartoum, dominated by Muslim Arabs.

For the Nuba, like Shatta’s father, opportunities were scarce. A musician, he found work in the Sudanese Army’s Silah Al Mousiqa (weapon of music), the military band. He died when Shatta was young and the family moved to Khartoum. “His passing broke our family. Poverty hit us. I had to drop out of school after the third grade because my family couldn’t afford it,” Shatta says.

In El Haj Yousif, one of Khartoum’s slums, Shatta and his seven siblings slept on the floor under a birish – a mat made from palm leaves. Soon, he was on the street. Child homelessness is common among ethnic minorities, driven by political and socioeconomic exclusion.

For decades, marginalised groups have resisted the government in Khartoum, which inherited the structure and systems of this oppression and intentional neglect from the colonial government.

The Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) ultimately cleaved South Sudan away from Khartoum’s control.

In the Nuba Mountains, armed conflict continues under Abdelaziz Adam al-Hilu’s SPLM-North faction, which joined the parallel government of RSF leader Hemedti. They intend to govern western Sudan parallel to the government coalescing around the SAF in Khartoum.

Reaching for common ground

Shatta’s life changed when a Canadian charity brought him in off the streets, and he was taken in by the family of a friend from the privileged Arab Ja’alin community. Living in Khartoum’s AlMamoura neighborhood, he re-enrolled in school and met renowned painter Hussein Gamaan, who recognised his talent and encouraged him to enter the arts programme at the Sudan University of Science and Technology.

Within a few years, Shatta was exhibiting alongside Gamaan in Khartoum. But as the 2011 South Sudan referendum approached and clashes erupted between the SAF and SPLM-North, Shatta came under suspicion for frequently travelling to his hometown in South Kordofan for photography.

Leaving most of his art behind, he took a bus to Juba, passing himself off as South Sudanese for months. Then, news came that one of his earlier works had won a Unesco competition in Paris. He travelled to France to receive the award and then to Oslo in late 2011, where he applied for political asylum.

“Talking to other asylum seekers from all over the world helped me realise how much our stories overlapped. We were all carrying trauma, navigating systems, and trying to find a sense of belonging.”

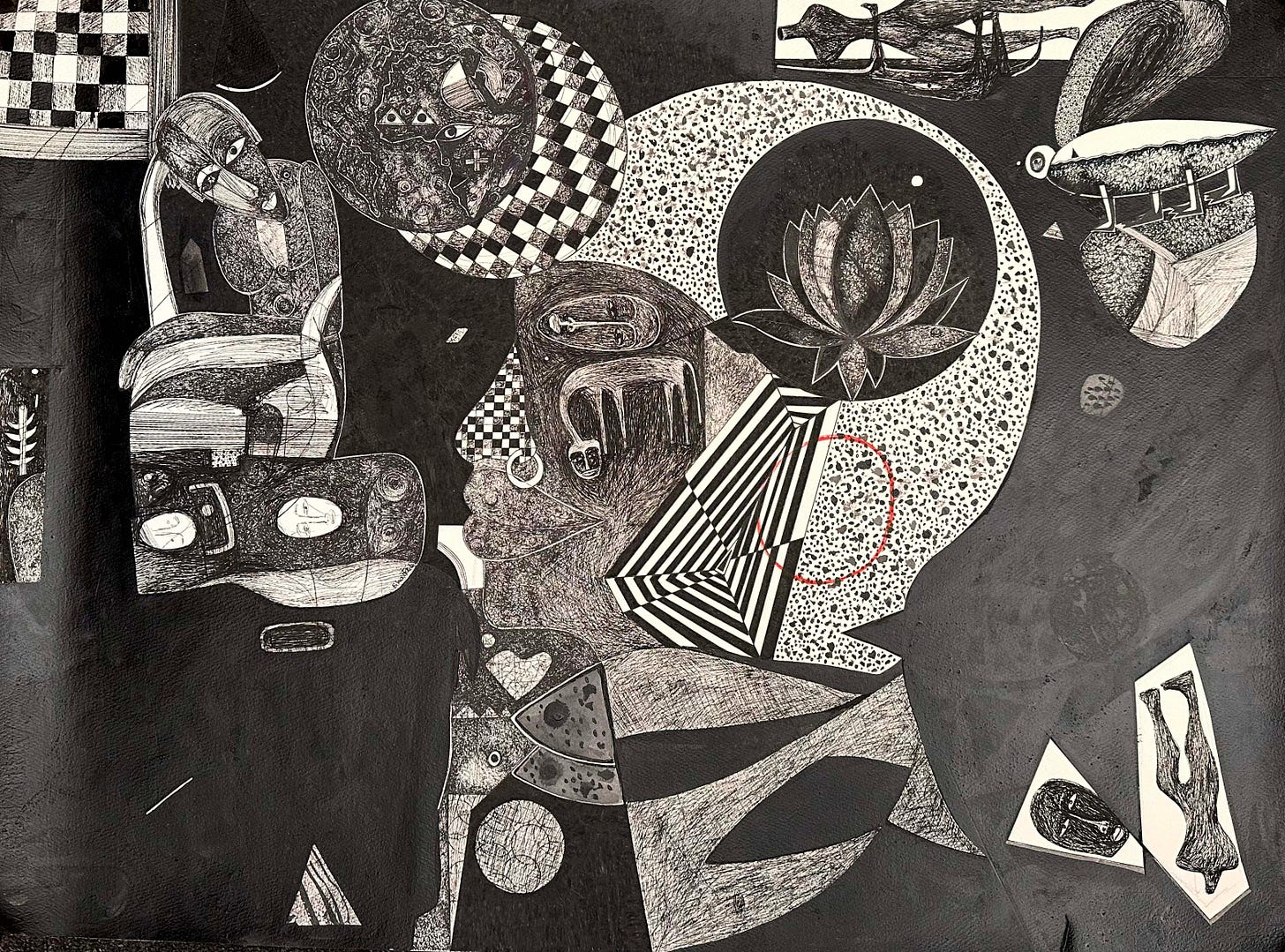

Shatta graduated from Prosjektskolen Kunstskole’s two-year arts programme and now views his art as both Norwegian and Sudanese. Using ink and acrylics, he explores indigenous systems of knowledge and belonging. “I became fascinated by the similarities in the emotions behind these acts of seeking.”

At a time when his first country is tearing itself apart over identity, Shatta has made a deliberate choice to show his latest exhibition to a displaced Sudanese community, in collaboration with another displaced Sudanese artist.

His Gods in Action exhibition at the Kamene Cultural and Research Center in Nairobi, is a deeply personal exploration of identity, indigeneity, spirituality, and resilience. His intricate ballpen drawings share the space with sculptures and installations by Heraa Hassan, who has lived in Nairobi for a year since fleeing the war in Sudan.

“I hope to show that there are larger, unifying concepts that can still create common ground for connection.”