South Africa is (still) ANC country

The big takeaway from this election is less about the weaknesses of the African National Congress, and more about its enduring strength.

Simon Allison in Johannesburg

There are plenty of good reasons for South Africans not to vote for the African National Congress. The oldest liberation movement in Africa has now led the government of South Africa for 30 years.

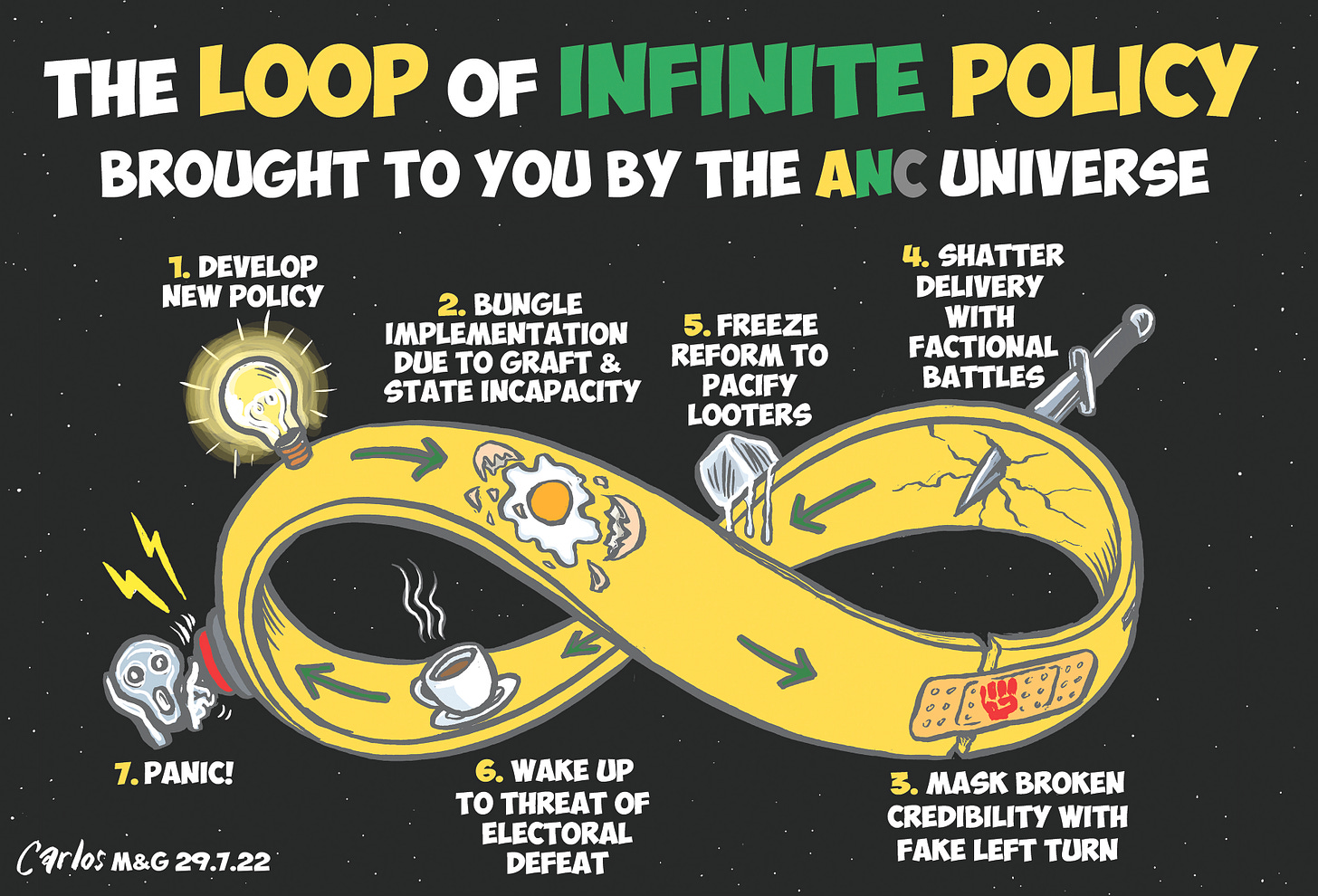

Over time, its weaknesses have compounded, and been repeatedly exposed under the relentless glare of media and civil society.

So dominant has its rule been that its failures have become those of the country, too: the corruption, the crime, the failure to create jobs, the rising cost of living, the glaring inequalities, and the lack of preparedness for the unfolding climate crisis. In the most obvious metaphor for its decline, the party in power can no longer keep the power on – except, curiously, in the months leading up to next week’s election, when the state utility burned billions of rands worth of diesel to temporarily suspend rolling blackouts.

And yet, on Wednesday, citizens of Africa’s largest economy will almost certainly vote the ANC into office once again. Its victory will not be as emphatic as usual – the party has never previously won less than 62% in a national election – and its majority may not even be absolute. It may have to form a coalition. But even the most damning polls suggest that 40% of the country will once more put their faith in the party of Oliver Tambo and Nelson Mandela (and, more recently and less laudably, of Jacob Zuma and Cyril Ramaphosa). That number is edging higher as the election draws nearer.

In some countries, support for the ruling party is vastly inflated by gerrymandering and ballot-rigging. This is not the case in South Africa, where there is little suggestion that the election will be anything other than one where people can vote freely. The ANC really is still the most popular party in the country.

This is partly due to the “liberation dividend” – a loyalty enjoyed by many liberation movements when they eventually do take power. This loyalty is not entirely misplaced. For all its faults, South Africa has plenty of reasons to be grateful to the ANC. It ushered in multiparty democracy in 1994, and avoided a civil war. In office, it dismantled the apartheid regime and extended basic services – designed by the apartheid government to service only the white minority – to most of the country. It also enabled the creation of one of the world’s most liberal Constitutions, and an environment where media are able to publish in the public interest, often detailing the ANC’s failures.

For many voters, especially those who lived through the horrors of apartheid, nothing the ANC can do is worse than the government it replaced. This point is often overlooked by foreign commentators with short memories. In an especially egregious example of this, Britain’s The Times wrote last week that “30 years after black people got the vote, South Africa is the most unequal society on Earth” – as if, somehow, South Africa was more equal under white supremacist rule.

The ghosts of apartheid

It helps the ANC enormously that the official opposition has done so little to banish apartheid’s ghosts. The Democratic Alliance has had just one black leader in its history, Mmusi Maimane – and it booted him after a disappointing electoral performance in 2019. Former DA leader Tony Leon later described Maimane’s tenure as a “failed experiment” and, sure enough, the party replaced Maimane with a white man.

Fed up, a succession of senior black officials have left, reinforcing perceptions it is a white-run party that caters to elites.

“The racism I experienced in the DA was not overt. Rather, it was that less honest, covert, paternalistic, difficultto-put-your-finger-on-it kind of racism,” said Herman Mashaba, a former DA mayor who quit to start his own party, writing in the Mail & Guardian in 2021. “It was the kind of racism that questioned why we were spending time delivering services to informal settlements when they don’t represent ‘traditional DA voters’ and ‘those who pay the rates’.”

In response to a question from The Continent, the DA’s leader John Steenhuisen said comments like these came from people who were “bitter and angry” after losing party leadership contests. But he appeared tone deaf when it came to the sensitive issue of race relations in South Africa. When asked if the country was ready for another white man as president, he compared himself to Barack Obama, “a minority in America, and he was able to get elected”.

The prospect of John Steenhuisen getting himself elected is slim, however. He has said that winning just 22% of the vote would be a major achievement for the DA – a strikingly limited ambition for a well-established opposition party operating in a free and fair political environment, and competing against a corrupt and scandal-prone ruling party.

Other opposition parties are making plenty of noise, but failing to attract support in the kind of numbers that would pose a real threat to the ANC. The Economic Freedom Fighters, led by Julius Malema, is on track for around 10% of the vote, according to polls, matching its performance from last time.

Newcomers uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), led by former president Jacob Zuma, are the biggest surprise. Polls put them at around 13%, but their appeal is largely limited to areas of the country – like KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng – with large Zulu populations. And the Constitutional Court last week ruled that Zuma, sentenced to time in jail for contempt of court, cannot stand for the national Parliament, which thwarts some of their higher ambitions.

But while there is no doubt that the ANC will remain the most popular party in the country, it should still be worried about the decline in its support. The extent of its worries will depend on the exact percentage of that decline. Should it retain over 50% of the vote, then it will have a majority of seats in the National Assembly – and that will allow it to appoint the president unilaterally. If it dips to 40% or below, it will need to work with at least one major opposition group – the DA, the EFF or MK – in order to form a government. If the track record of local government coalitions is anything to go by, this will be a messy process.

The most likely scenario is that the ANC receives somewhere between 40% and 50% of the vote. This should allow it to form a coalition government with smaller parties – outfits like the newlyformed Rise Mzansi, whose policies are strikingly similar to those of the ANC, but who position themselves as the “grownups” in the room in any coalition scenario. They will be able to extract minor concessions, but won’t be in a position to shape the government as a whole. This is still ANC country, after all – at least until 2029.

Want to know more about next week’s election? The Continent’s partner Democracy in Africa is helping organise an X Space that will break down all that is at stake, with people in the know. Set a reminder here.