Sharangabo learns to bet on himself

After his big debut, the Rwandan filmmaker reflects on greenlighting one’s own dreams, even before the gatekeepers do.

Wilfred Okiche

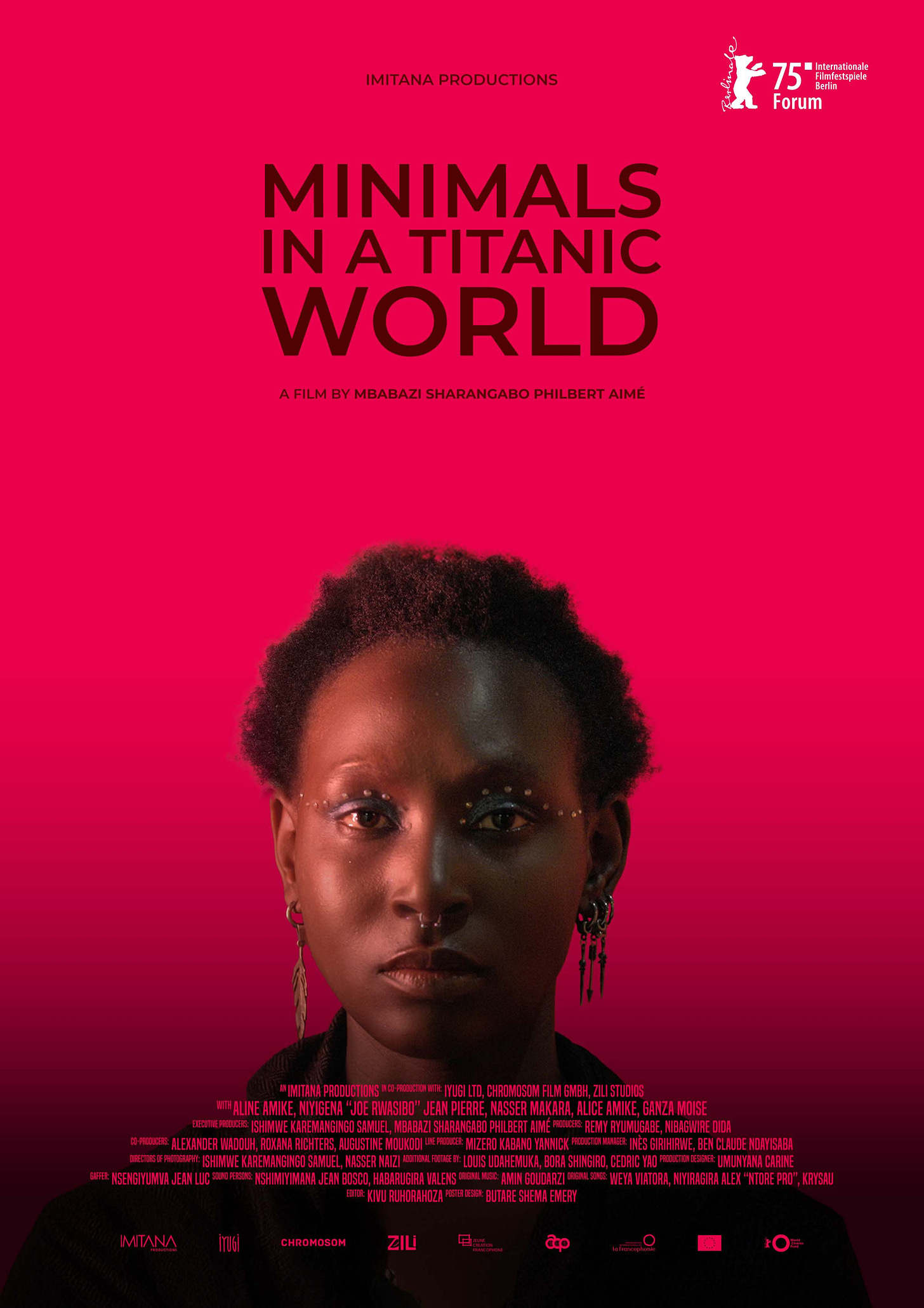

Not many filmmakers get the opportunity to present their first feature film at the Berlin International Film Festival, one of the biggest film festivals in the world. This was exactly the rarefied situation that Rwandan filmmaker Philbert Aimé Mbabazi Sharangabo found himself in this February with his modestly realised drama Minimals in a Titanic World.

“I am interested in outsiders,” Sharangabo tells The Continent. “My characters are not on a spectacular or epic journey, and they aren’t saving the world. But for the 80 minutes that we follow them, these small characters matter.”

A contained reflection on grief, Minimals in a Titanic World was inspired by a contemplative short film titled I Got My Things and Left, which Sharangabo made in 2018.

His new work considers a close-knit group dealing with the sudden loss of their friend, and takes place mostly in the large, imposing house where they all live together – but there’s also a significant Kigali nightlife scene where the protagonist Anita (Aline Amike), just out of prison for a petty crime, performs at a bar while hoping to kickstart a career as a songwriter.

Despite the loss and grief that grounds the film, it is also a celebration of life, a knotty tribute to the youth of Rwanda. The main characters of Minimals in a Titanic World can no longer afford the house that they live in. They depended on the generosity of their deceased friend, whose sudden passing ejected them from this bubble. Sharangabo’s observant and expressive gaze captures a particular mood and lifestyle that is at once hopeful, yet challenged by obvious economic and class realities.

“I wouldn’t like to make a miserabilist film,” says Sharangabo. “I fell in love with cinema through characters, and it is very hard to admire or fall in love with a victim.”

Lead actress Amike, says that what she liked most about the role was the sheer willpower of the character Anita. “She is grieving but still making space to dream big, despite not having a lot to work with.”

As a first-time feature filmmaker, Sharangabo recognised that he had to bet on himself, he tells The Continent. “For us, it was about not waiting for better conditions. But we never really had any alternatives.”

Along with his producers, Sharangabo raised some initial funds in March 2023 and shot about 70% of the film before taking a production break to edit and to raise additional funds. Cast and crew lived in the house that appears in the film for most of the 23-day shoot. Ten months into the break, a complex balance of co-production agreements in Africa and Europe helped to raise postproduction funds, enabling another 10 days of shooting in January 2024.

But Sharangabo didn’t skimp on labour ethics. “It was a low-budget film, but the idea was that everybody should be paid. I am sure we could have asked people to show up for free and they would’ve done it. But that’s not what we were aiming for.”

He stresses that younger filmmakers should greenlight themselves, and not wait on gatekeepers.