Review: How to keep a promise

Photos from a different time still need their space in today’s world. A commitment to archiving allows us to experience the stories behind them.

Wilfred Okiche

In 2002, Ntare Guma Mbaho Mwine, an actor and filmmaker (currently seen in Apple TV+’s Smoke) was passing through the small Ugandan town of Mbirizi when his car sputtered to a stop. While waiting for repairs, he wandered off with his camera and stumbled on a modest studio run by Ssalongo Kibaate Aloysius, a local photographer. This chance encounter would blossom into a friendship, and also a 22-year odyssey to bring Kibaate’s work to wider public attention.

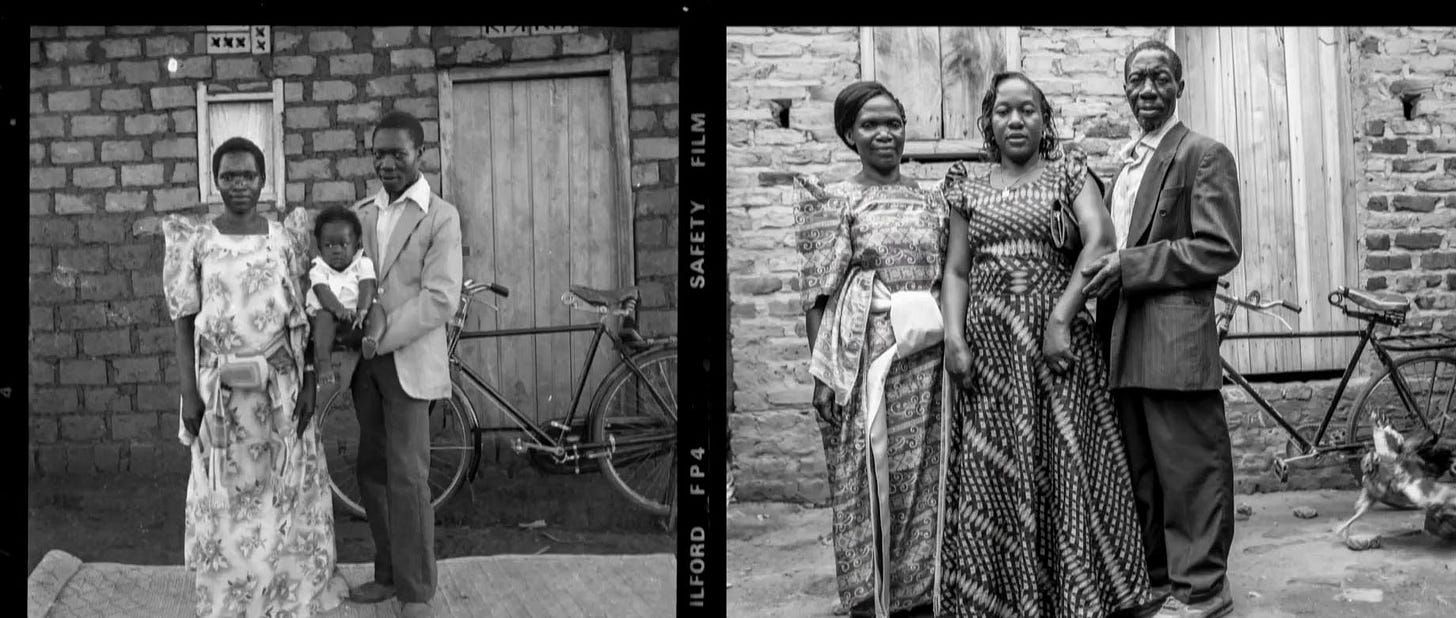

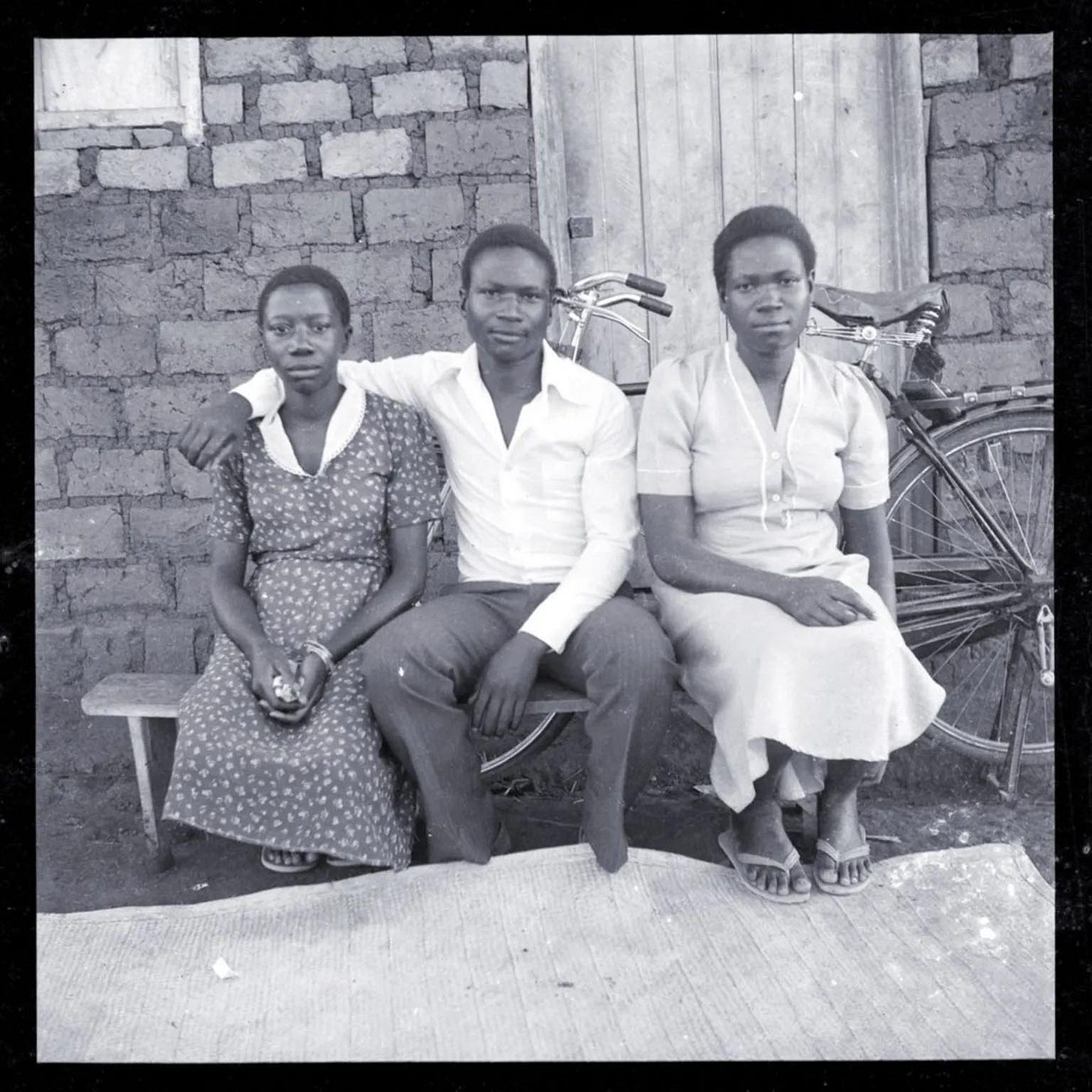

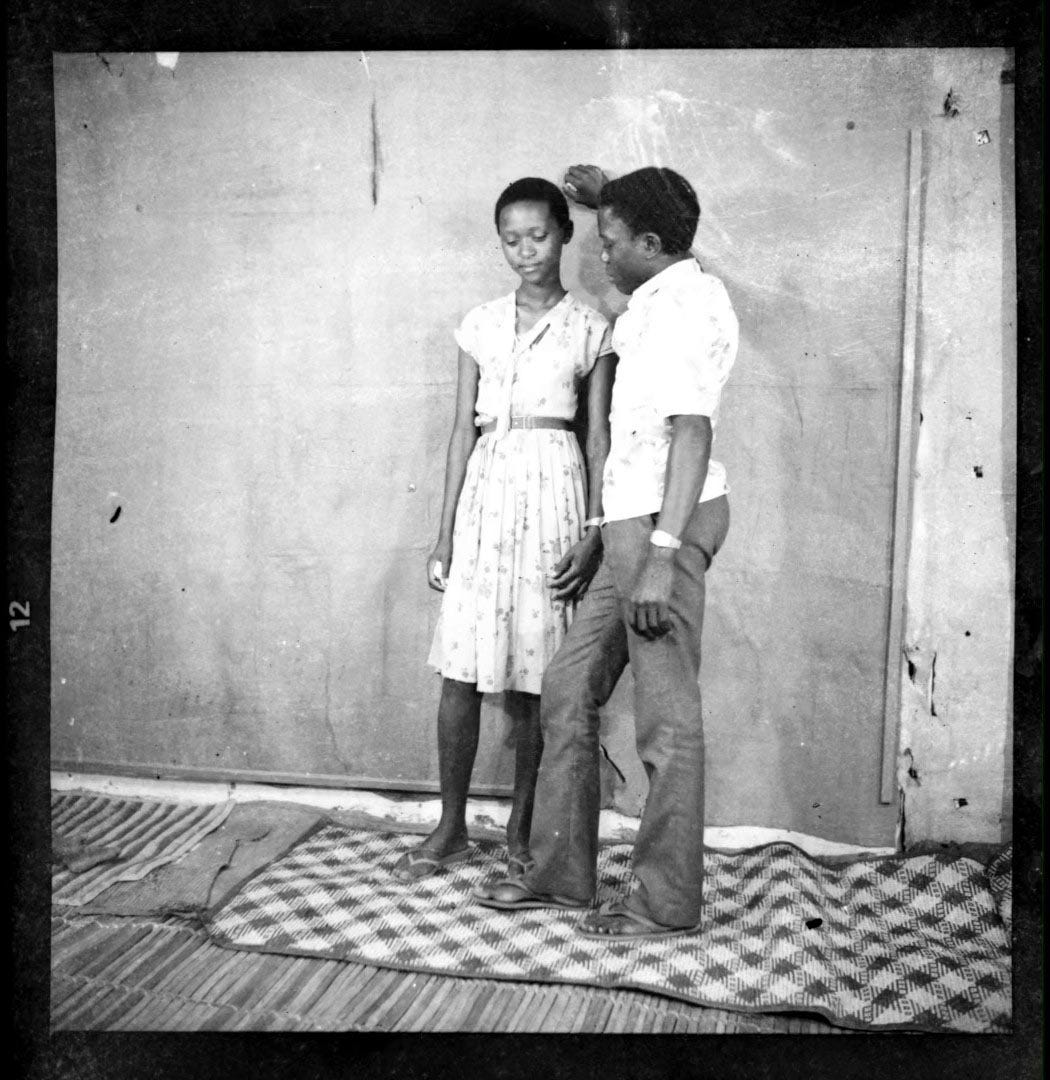

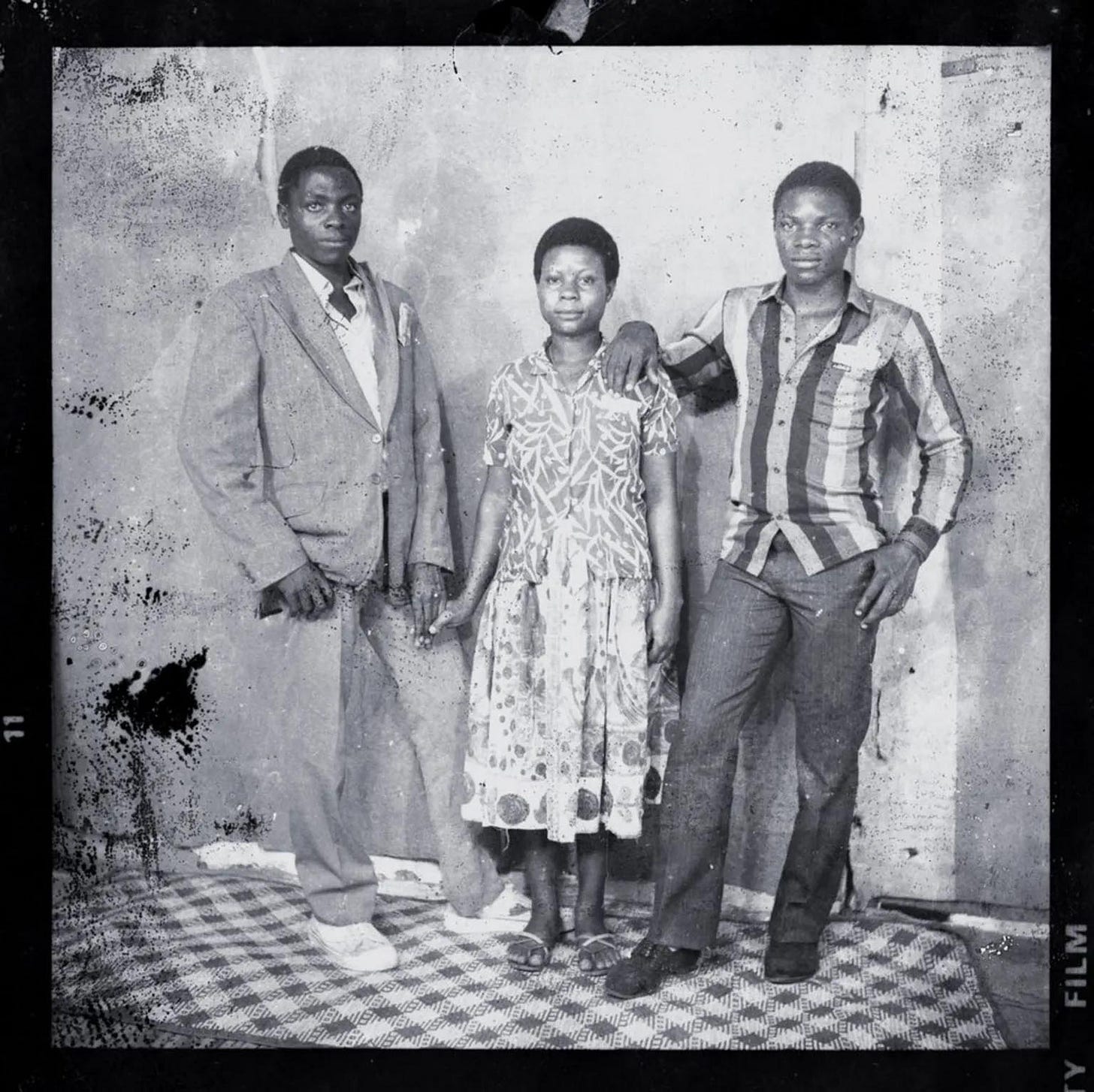

“Kibaate showed me thousands of negatives he had in a burlap sack and I was blown away,” Mwine tells The Continent. “He wasn’t a city guy photographing elites. He was shooting the common man – weddings, birthdays, family events. What was special was how he captured intimacy.”

Kibaate had no ambitions for fame or wealth: his photography was a service to his community, driven by what Mwine calls “the pure artist’s love of his work”. Mwine, who was born in the United States to Ugandan parents, has often wondered what his own life would have been like had he been born in Uganda. “I look at Kibaate and his life could have been mine,” he says.

Kibaate passed away in 2006 at the age of 67, leaving Mwine tortured by a promise to make his work more accessible. “I don’t know if you’ve ever made a promise to someone who died – it sort of haunted me,” he says. “I have his negatives, and promised to make a book. But could not afford to digitise all his work as I was self-financing.”

Mwine’s debut feature documentary Memories of Love Returned chronicles his efforts to keep that promise. The film premiered at the Silicon Valley African Film Festival, showed at Fespaco, and won an award at the Zanzibar International Film Festival. The documentary is structured in a way that melds Kibaate’s story with Mwine’s personal reflections. In the process, it offers clear-eyed commentary on history, legacy, and patriarchy.

The film’s title is taken from the roadside exhibition of about 5,000 of Kibaate’s photographs, which Mwine mounted in Mbirizi in 2021 during the Covid pandemic. Mwine put his first paycheck from the Showtime hit series The Chi towards preserving Kibaate’s archive and funded the exhibition with a donation from director Steven Soderbergh, with whom he had worked on 2014’s The Knick. His small team collected the stories of attendees as they identified their friends and relatives among the photos.

Kibaate’s photography is striking in its tenderness. “We celebrate Malick Sidibé, as we should,” Ntare says of the renowned Malian photographer, “but he often photographed elites. Kibaate’s work was working-class people. His photos didn’t feel staged. He captured love and affection so simple, but that spoke volumes.”

These images also reveal Uganda’s shift to more conservative values. Men holding hands, common in earlier decades, now evokes speculation. “We don’t know their stories, whether [they were] gay or straight, but that is besides the point. People don’t hold hands like that anymore because they do not want to be stigmatised,” Mwine says. “Kibaate’s work shows us a time that was more open.”

Other photos complicate gender and morality narratives. One woman, frequently pictured with different men, is revealed to have been a sex worker. “She owned a bar. She was enterprising and people looked at her like a hero,” says Mwine, cautioning against easy judgment. “Our biases shape how we interpret these images.”

Mwine also wants the film to open discussions about archiving, particularly in the digital age. He has come to fear the loss of digital memory even more than the decay of analogue negatives. “Modern photographers shoot digital, print for clients, then delete their cards as they don’t have the storage facility to keep all of the work they shoot. That’s scary.”

He is still working on the second part of his promise to Kibaate: publishing a book of selected photographs. He hopes that as his labour of love continues to travel and reach new audiences, the project’s revenues can help to support the large family Kibaate left behind.