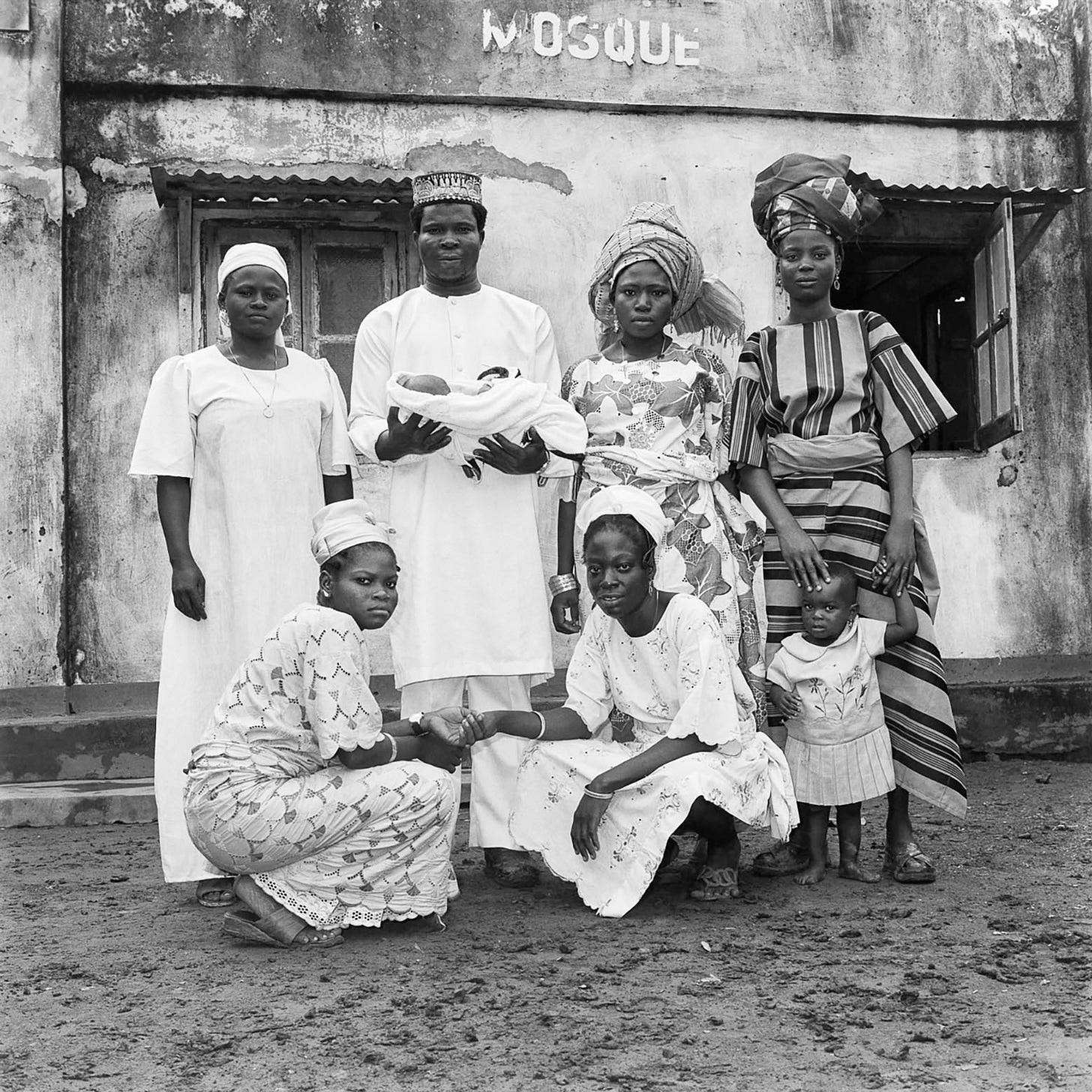

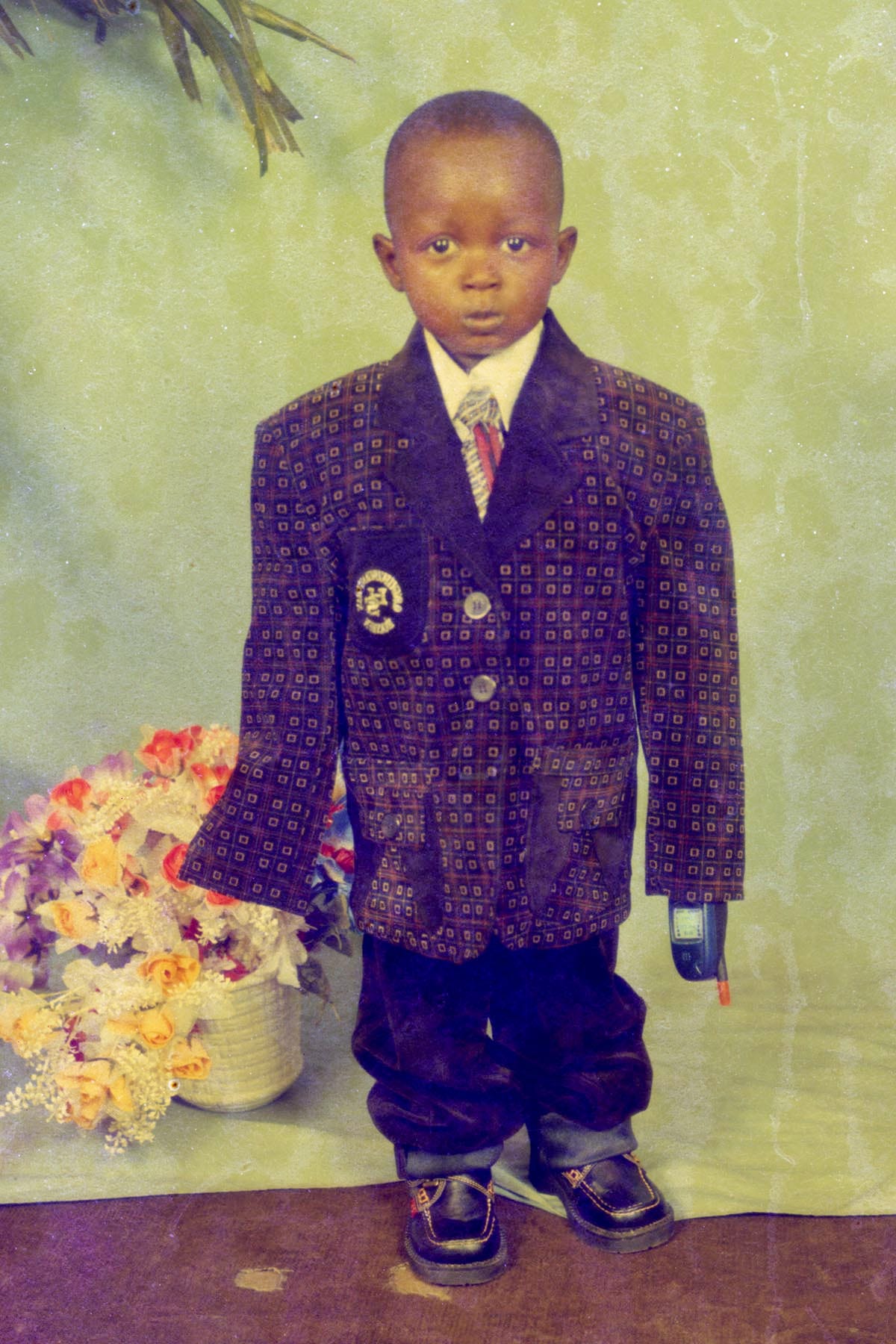

Photo Essay: Old Lagos, new light

In studios across the city, negatives lay gathering dust. Now those forgotten negatives are being developed – bringing Lagos’s history into focus.

Paul Botes

When Karl Ohiri asked to see the archives of an old studio photographer who worked in Owerri, the capital of Imo state, he got a startling response. “I burnt them.”

Visiting other studio photographers in Lagos, he kept getting the same response: they had all destroyed their negatives. Digital photography had rendered them expensive and obsolete. Even knowing that, learning of their burning was jarring.

“I was concerned that parts of Nigeria’s social history could be permanently erased,” Ohiri told The Continent. So he decided to do what he could to archive studio photography that showed the lives and styles of local Lagosians – snapshots of the city that would otherwise be lost.

Enlisting the help of the local photo community, he amassed thousands of negatives. Many had been poorly stored and had deteriorated substantially in the city’s humidity. Some were delivered in old rice sacks, full of rat droppings. Riikka Kassinen partnered with him on the effort in 2022. Their joint venture, Lagos Studio Archives, now has hundreds of thousands of old, forgotten negatives.

Dating the archives accurately has proven a challenge, as many of the negatives were kept or retrieved without dates. Karl and Riikka have relied on fashion from the time and occasional photographs with books, magazines or calendars in them.

Many of the bodies of work are orphaned as the photographers have since passed away. One collection that stands out is the Abi Morocco Photos, consisting of more than 5,000 negatives. Mostly photographed in black and white on medium-format cameras, and dated, the collection came from a joint venture between Funmilayo and John Abe, a husband and wife team. Ohiri and Kassinen met the couple in 2020 and developed a close friendship.

Abe, a studio photographer, met Funmilayo, also a photographer, in 1973. She would use his darkroom.

They talked about their shared passion for photography. Shortly after, they decided to join studios under John’s name, Young Abi Morocco Photos. (“Young” was dropped after a few years when a friend joked that Abe was getting on in age).

Abi Morocco Photos was located on the bustling Aina Street, in the north of Lagos, for 18 years. It then moved to nearby Shogunle – equally busy and bustling – for another 18 years.

The studio was popular, and the couple expanded their practice to include studio portraiture, commissioned home and street portraiture, celebrations and funerals.

They had a Vespa motorcycle with Abi Morocco Photos emblazoned on the windshield and travelled all over Lagos to commissions or when delivering prints. Both often worked late into the night, making prints in the darkroom, their home adjoining the studio. John retired in 2006, and with it, the studio. Funmilayo continued photographing until 2021.

Karl and Riika recount that John, who passed away last year, regarded photography as an important educational tool for preserving history and stories, and shared their passion in keeping Nigeria’s social history alive.