Out of Egypt: Art flows where the money goes

Arab artists are leaning east towards the Gulf states, which are pouring billions of dollars into culture to push past their ‘petrostate’ image on the world stage. It’s hurting feelings in Cairo.

Fatma El-Zahraa Badawy in Cairo

Ta’araf Tetkallem Baladi, a classic song that debuted in a film by Egyptian director Youssef Chahine, says that “if you speak Baladi … and live the modern dream, then you are definitely Egyptian”. When Tunisian singer Latifa and Egyptian poet Gamal Bekheit performed the song in Dubai last October, they kept the tune but not the lyrics. Most controversially, they changed “then you are definitely Egyptian” to “then you are definitely Arab”. Uproar about the “Gulfisation” of Egyptian art promptly ensued in Cairo.

A year earlier, Egyptian singer Mohamed El Helw had caused similar uproar when, at a concert in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, he replaced Alexandria with Saudi Arabia in a praise song. The Jeddah crowd was thrilled, but in Egypt he faced so much backlash that the musicians’ union put out a statement defending El Helw’s right to change words in his own songs.

In Cairo, the two incidents were seen as part of an emerging and troubling trend: rebranding “iconic Egyptian cultural symbols in ways that obscure their origins and reassign their success to other nations, not just as patrons, but as original sources,” says writer and literary critic Hadeel El-Berry.

She speaks to a wider sense of Egyptian loss. For much of the 20th century, Egypt has been the beating heart of Arab culture. Today, however, it is increasingly overshadowed by the Gulf states.

New money trumps old

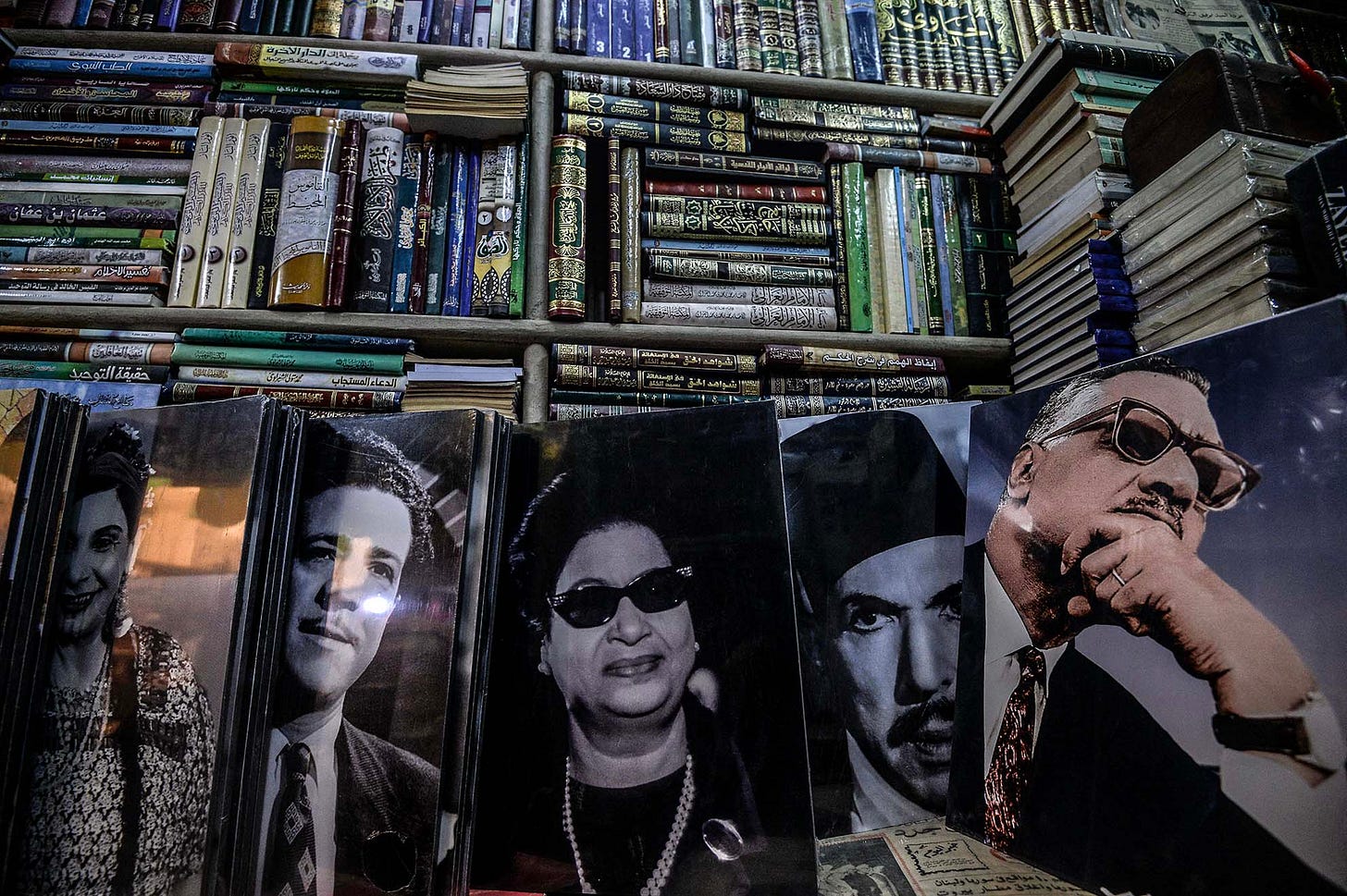

In the latter half of the 20th century, Cairo’s cinema and music ruled screens and airwaves in the Middle East. Egyptian luminaries like Umm Kulthum and Sayed Darwish inspired creators and listeners across the region. Egyptian literature, theatre and broadcast media shaped Arab identity. In the post-World War II era, Egypt welcomed Armenians, Greeks, Italians, and other exiled or persecuted foreigners whose diverse tastes and talents enriched its artistic scene.

“A relatively stable economy nurtured creativity and Cairo became a haven for artists from across the region, partners in a cultural renaissance spanning literature, cinema, and publishing,” explains contemporary visual artist Mohamed Abla.

Today, the Arab states across the Red Sea from Cairo are eager to diversify their own economies and international stature, beyond being linked to oil. They are pouring billions of dollars into their cultural and creative sectors, wooing Egyptian creators to their scenes and tastes.

Saudi Arabia – which didn’t have a culture ministry until 2019 – now has a mega culture development fund that includes at least $20-billion to attract foreign collaborators.

Neighbouring Dubai introduced the world’s first long-term cultural visa in 2019 to encourage creators to settle there. Under the scheme, Arab and global creatives can get up to ten years of residency without needing a local sponsor. The Louvre Abu Dhabi opened in 2017. Floating on an island in the Doha harbour is the iconic – if just 17 years old – Museum of Islamic Art. At the site where Saudi Arabia found its first commercial oilfield now stands the Ithra (or the King Abdulaziz Centre for World Culture). Opened just eight years ago, the 80,000m2 complex includes a museum, cinema, theatre, exhibition halls and a library which holds half a million texts.

The Gulf states want to build their creative economies to a level that Egypt has already attained: contributing at least 3% of national GDP. Saudi Arabia hopes that its cultural sector will generate $20-billion in revenue by 2030 and create 100,000 jobs. In Egypt, an economy that is less than a third of Saudi Arabia, the culture ministry alone employs up to 39,000 state artists and cultural workers and the wider creative sector generates more than $11-billion a year.

But Gulf states’ investment is big money flowing now, while Egypt’s is old money sunk in existing, and in some cases badly aging, cultural infrastructure and institutions. Cyclic political and economic crises mean that Cairo is not reinvesting enough to keep up. Last year, the Egyptian government cut public spending across all sectors by 15%.

So, creators are following the money – out of Egypt. Or at least tweaking lyrics.

What now?

Abla cautions against interpreting the talent migration as a cultural defeat for Egypt. “Art is not confined to its place of origin; it evolves with context. The movement of artists doesn’t mean Egypt is losing its place but reflects a natural interaction between cultures,” he says.

In his view, Egyptian creativity is going through a transformation akin that of other once-dominant cultural capitals like Paris. He also says that there is something to celebrate in the fact that the Gulf states are throwing money at Egyptian creatives. They recognise “the immense value of Egyptian artists” raised in a culturally rich tradition and are eager to incorporate that into their emerging initiatives, he says.

Not everyone sees the shift as a natural evolution rather than Egyptian failure. In recent years, inflation and cost-of-living pressures have slashed individual spending on cultural and recreational activities. In early 2024, for instance, spending on cinemas fell to $4.4-million from $15-million a year earlier.

Literary critic Shaaban Youssef says the government hasn’t done enough to cushion the cultural sector from these dips. “The government doesn’t treat culture as a priority,” he says. “Writers and artists are left without real support.”

Even then, all is not lost yet, according to El-Berry, the writer and literary critic. Egypt “retains the essential ingredients for a cultural resurgence,” she says.

In her view, “through strategic partnerships with Gulf states, Cairo is attempting to recalibrate the regional artistic landscape while preserving its historical identity as the region’s cultural heartbeat”.

Aren't those all Arab settlements in North Africa, a result of Islamic conquest as far back as the 7th century? Just like .. historically speaking. I believe they refer to it as "The Maghreb". The indigenous Africans in Morocco are the Amazigh and Berber people.. which would make those modern day settlements? And the people there profiteers off a history that is not theirs? And correct me if I'm wrong but isn't Egyptian leadership supplying arms to the war in Sudan and have done so for longer than much of the world is aware?