Oh, but how quickly the glory fades

Again and again, African athletes are celebrated today and forgotten tomorrow.

Kalungi Kabuye

Botswana’s Olympic athletes returned from Paris on Tuesday to a hero’s welcome. Their plane received a water salute on the runway, and Gaborone’s international airport was packed with jubilant crowds – President Mokgweetsi Masisi among them.

The athletes were then whisked off to the national stadium, where tens of thousands of fans had gathered to celebrate their success. The star of the show was undoubtedly Letsile Tebogo.

The young sprinter shocked the world to win the men’s 200m, and anchored a phenomenal silver medal-winning performance in the 4x400m relay.

The president urged the crowd to shower the athletes with gifts, and announced the reward of two houses for Tebogo, and a house each for the rest of the relay team.

Two decades ago, Uganda’s Dorcus Inzikuru was also awarded a house, but that was about it. She was the first Ugandan woman to win a gold medal in a major international contest: the 3,000m steeplechase at the World Athletics Championships in Helsinki in 2005.

When she got back to Kampala, Parliament held a special session in her honour, and she was invited to dine with President Yoweri Museveni. He promised her a car, a house and a stadium in her honour in her hometown of Arua, according to reports from the New Vision newspaper.

The car never materialised. The small local stadium bearing her name is so dilapidated that goats graze on its field. And local authorities want to demolish her house to make way for a new road. Usually, homeowners would receive compensation for this – but Inzikuru was never given the property’s title deed.

How quickly we forget our heroes.

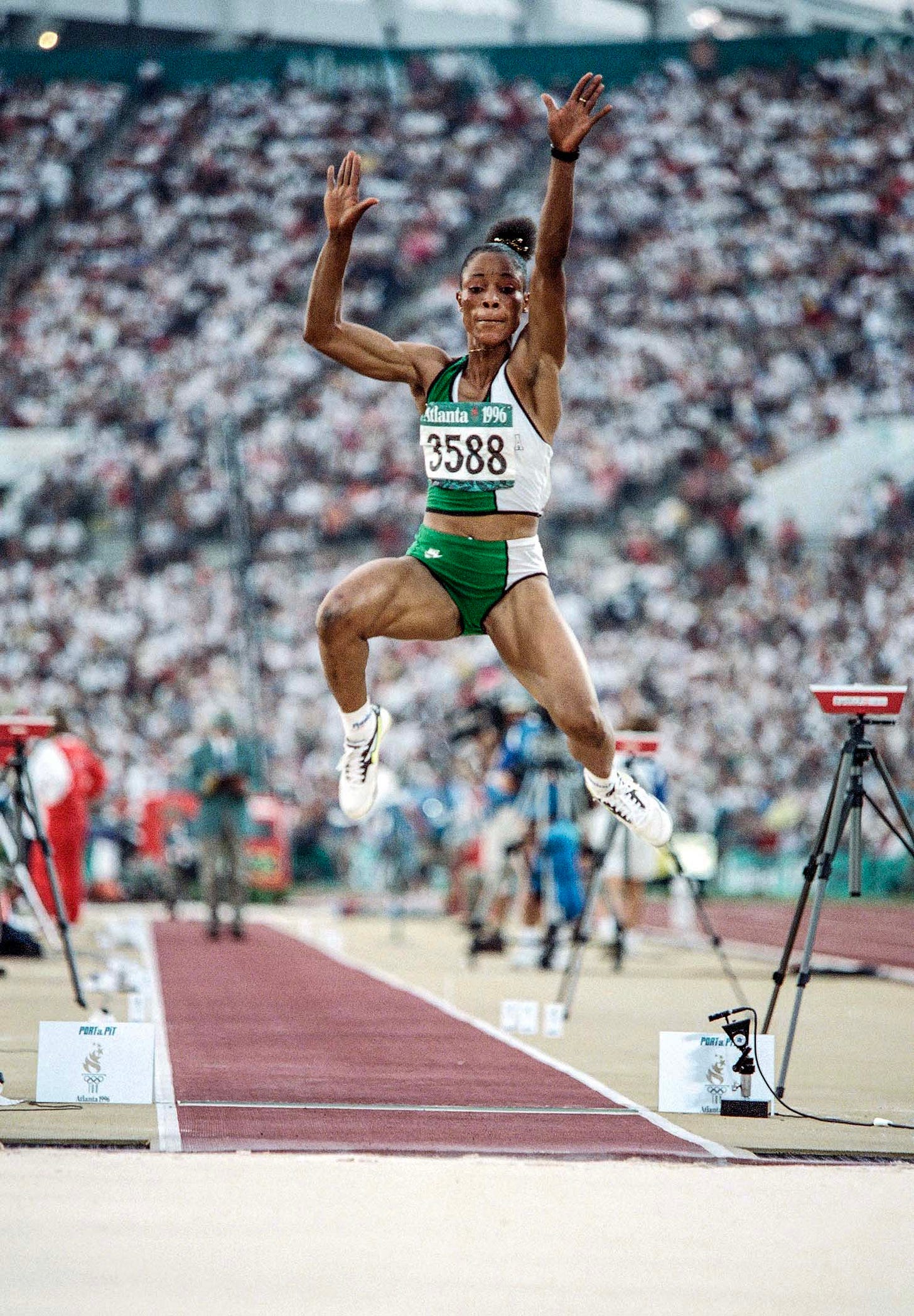

Just ask Chioma Ajunwa. In Atlanta in 1996, in the long jump, she became the first – and, to this day, only Nigerian to win an individual gold medal at the Olympics.

On her return, Nigeria declared a three-day public holiday, and decorated her as a Member of the Order of Niger. She appeared on TV and toured the country in a motorcade, according to Bella Naija. By 2003, the glitter of her gold was a distant memory. Ajunwa was no longer fêted by the country’s sporting fraternity, but complained about being overlooked and ignored – perhaps because she was (and remains) critical about the quality of sports administration in the country.

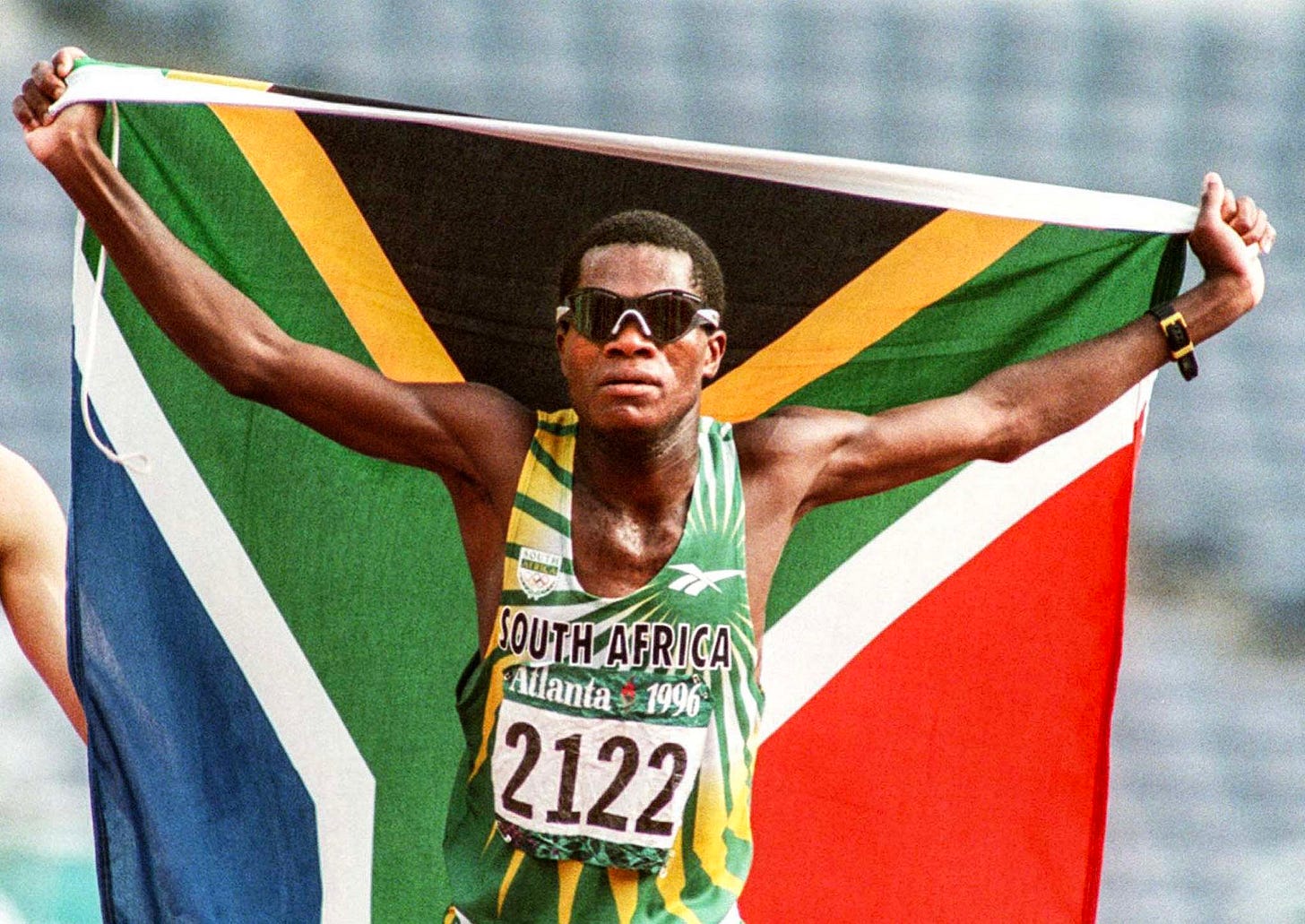

“I toiled so much for this country but then I was dumped,” Ajunwa told Vanguard newspaper. “That I could be the only individual gold medal winner for Nigeria in over half a century of participation in the Olympics and still be treated like a scourge, I couldn’t believe it.” Her story is echoed by Josia Thugwane, the first black person to win an Olympic gold medal for South Africa. He ran, and won, the men’s marathon in Atlanta 1996 – just two years after the end of apartheid.

And he did it with no formal training, while working as a janitor at a coal mine.

At the time, Thugwane’s against-all-odds victory seemed to symbolise the promise of the new South Africa, and he was treated accordingly: there were endorsement deals, parades, and a meeting with president Nelson Mandela.

But when ESPN checked in on him a couple of decades later, the crew found Thugwane at a farmhouse in rural Gauteng.

All that spoke to his glory days were two pictures on the wall: one with Mandela, and another in which he is surrounded by excited school children. The tracksuit he wore so proudly in Atlanta was tucked away in a closet.

He spent his days watching television, and his evenings tending to cattle. He wasn’t living out his dreams.

“My dream was to help the young and talented athletes in South Africa. I failed in this goal because I don’t have the money from the government or sponsors to help them,” he said.

Wherever you look, there are similar stories: Charles Asati, part of the Kenyan in Munich in 1972, lives alone in western Kenya in a house without electricity, according to The Nation; Eridadi Mukwanga and Leo Rwabogo, the boxers who won Uganda’s first Olympic medals at the 1986 Games in Mexico City, both died destitute.

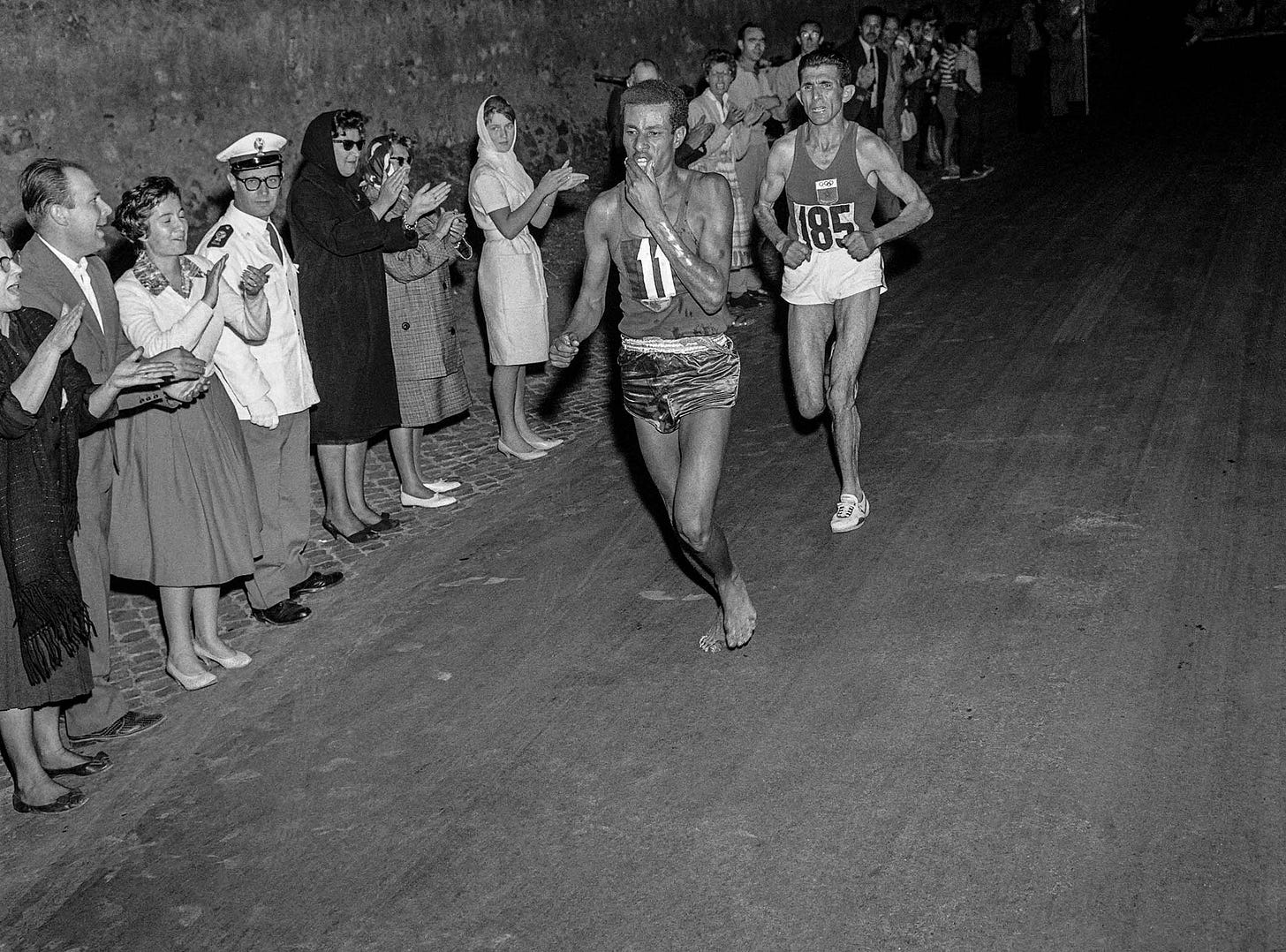

And, speaking of faded glory: in Ethiopia, which treats its athletes better than most, the tombstones of Abebe Bikila and Mamo Wolde were vandalised in 2006. The two marathon runners, who between them won the 1960, 1964 and 1968 Olympic marathon gold medals, laid the foundation for Ethiopia’s distance-running dynasty.

But no one bothered to repair the damage done to their gravestones, until a Japanese photographer happened upon them many years later and raised funds team that won gold in the 4x400m relay for their restoration.