Mukanya’s last dance

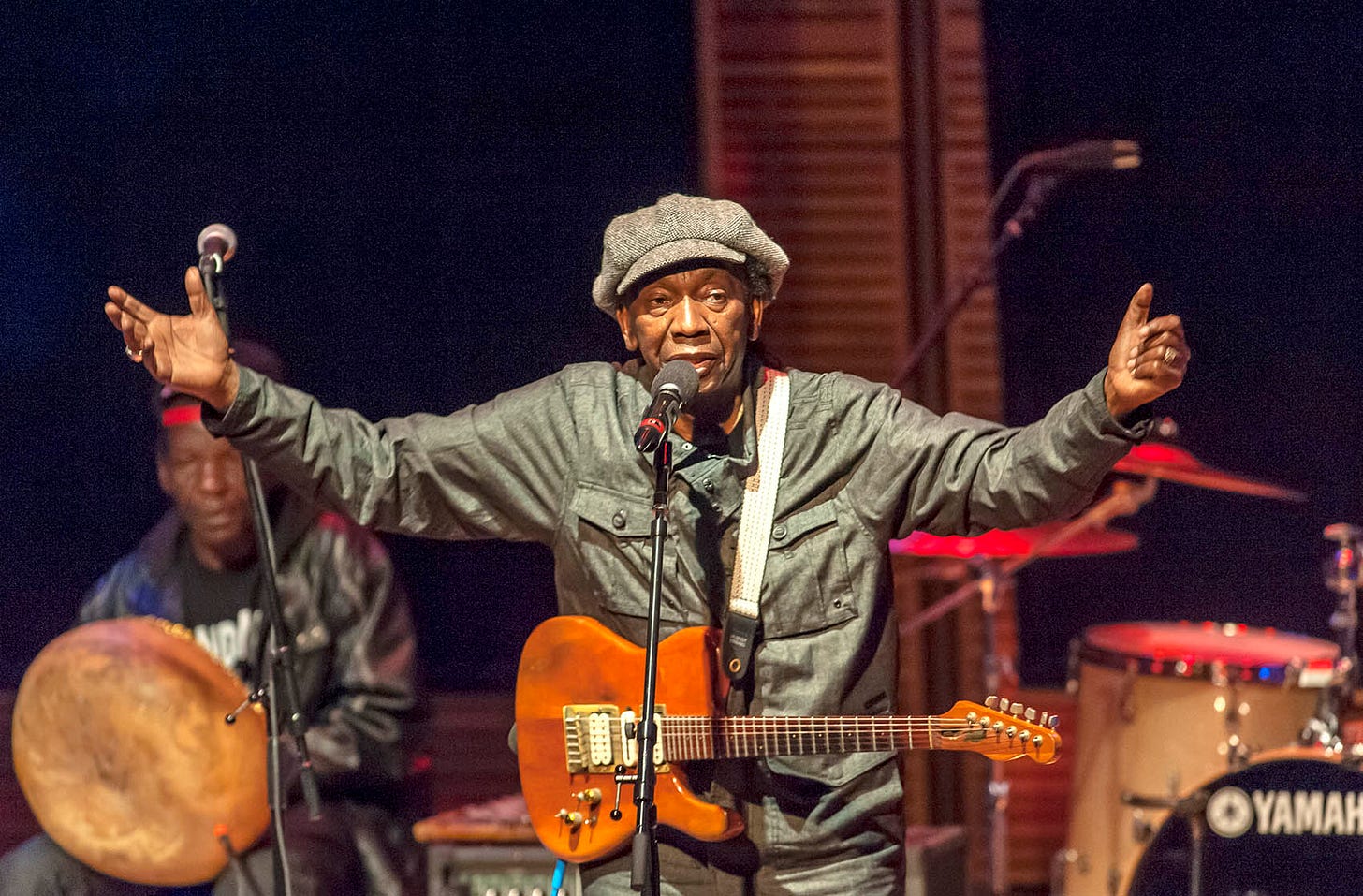

The Lion of Zimbabwe, Thomas Mapfumo, plans to leave the stage – but not the music.

Thomas Tafirenyika Mapfumo was forever changed by a white man who shouted, “Shut up you kaffirs!” at his band, as they came to the end of their rendition of Elvis Presley’s The Last Time.

Back then, in the 1970s, Mapfumo, like many of his peers, was enamoured with rock and roll, and Presley’s showmanship and swagger. So, “this blatant racist episode hurt me a lot and made me think that: we are not allowed to sing foreign music,” he told The Continent over the phone from his home in Oregon, US.

But it also made him realise that he could just as easily borrow from the musical traditions of Zimbabwe and wider Africa.

Overlaying Zimbabwean and other African oral storytelling traditions with mbira, drums and guitar riffs set Mapfumo apart as a musical virtuoso. In his prime, while on stage, he’d swirl to the mbira and drums, head bowed, dreadlocks swaying, seemingly in devotional connection with the world yonder.

Fans would chant “Mukanya, Mukanya, Mukanya!” a reference to Mapfumo’s baboon totem.

A speaker of hard truths

Unlike his surname, the plural of a spear, a weapon used to pierce the enemy from a safe distance, Mapfumo’s lyrics have always been direct and confrontational, earning him the moniker “The Lion of Zimbabwe” – beautiful, militant, mystical, poetic and dangerous.

“During the 1970s war, Mapfumo had made himself a legend with slyly political songs sung in an African tongue (Shona), and referencing sacred traditional music that had been systematically stigmatised by Rhodesian officials,” says Banning Eyre’s book, Lion Songs: Thomas Mapfumo and the Music that Made Zimbabwe.

In 1989, nine years into independence, graft was rife within the echelons of the new elite. Mapfumo released Corruption. The hard-hitting album soon drew the ire of Robert Mugabe’s regime. Mapfumo was eventually forced into exile and the album confined to selected bars and homes.

After Mugabe was deposed, Mapfumo triumphantly returned to a Zimbabwean stage in 2018. The gig became a pungwe, an all-nighter, that delighted fans spoke of as an almost spiritual experience.

The truce with Zimbabwean politicians did not last. Mukanya keeps ruffling feathers, asking as he did in his 1998 song: “Ndiyani Waparadza Musha?” – who destroyed my home?

“I once called the main opposition leader, Nelson Chamisa, regarding the [August] elections and I told him not to accept them without reforms, without foreign observers, and the voters roll,” said the musician.

He is so concerned about repercussions for his continued interest in Zimbabwean politics that he did not attend the funeral of his brother and bandmate Lancelot, who passed away last year.

Now aged 78, after gracing global stages for five decades, Mapfumo wants to leave the stage, but on his own terms. He plans to release one more album but has decided he will retire from live performances and instead spend his energy on supporting upcoming musicians.

But his retirement venture will roll out with a caveat – one that suggests that the racial aggression of that 1970s white man still cuts. He too became something of a music culture separatist. He wants to support upcoming musicians to “promote their own music and culture, not music from other foreign nations.” He says of people who prefer Zimdancehall, “you are despising your own music and culture and encouraging foreign music.”