Meet the people in the machine

Behind the miracle of supposedly autonomous software is an army of underpaid, exploited and vulnerable data workers.

Simon Allison

Famously, the titans of Big Tech look after their employees. Tech workers receive lavish salaries and scarcely believable perks on glittering campuses in the United States designed by some of the world’s leading architects. The perks include free gourmet meals, fresh juices and barista-made coffees, laundry services, valet parking, access to gyms and yoga studios, and psychologists on call when everything gets a bit much.

The Nairobi offices of Sama – an outsourcing firm that has provided services to tech giants including Meta and OpenAI – are very different, according to some former employees, who speak about their experiences in the Data Workers’ Inquiry, a new report published by the Distributed AI Research Institute.

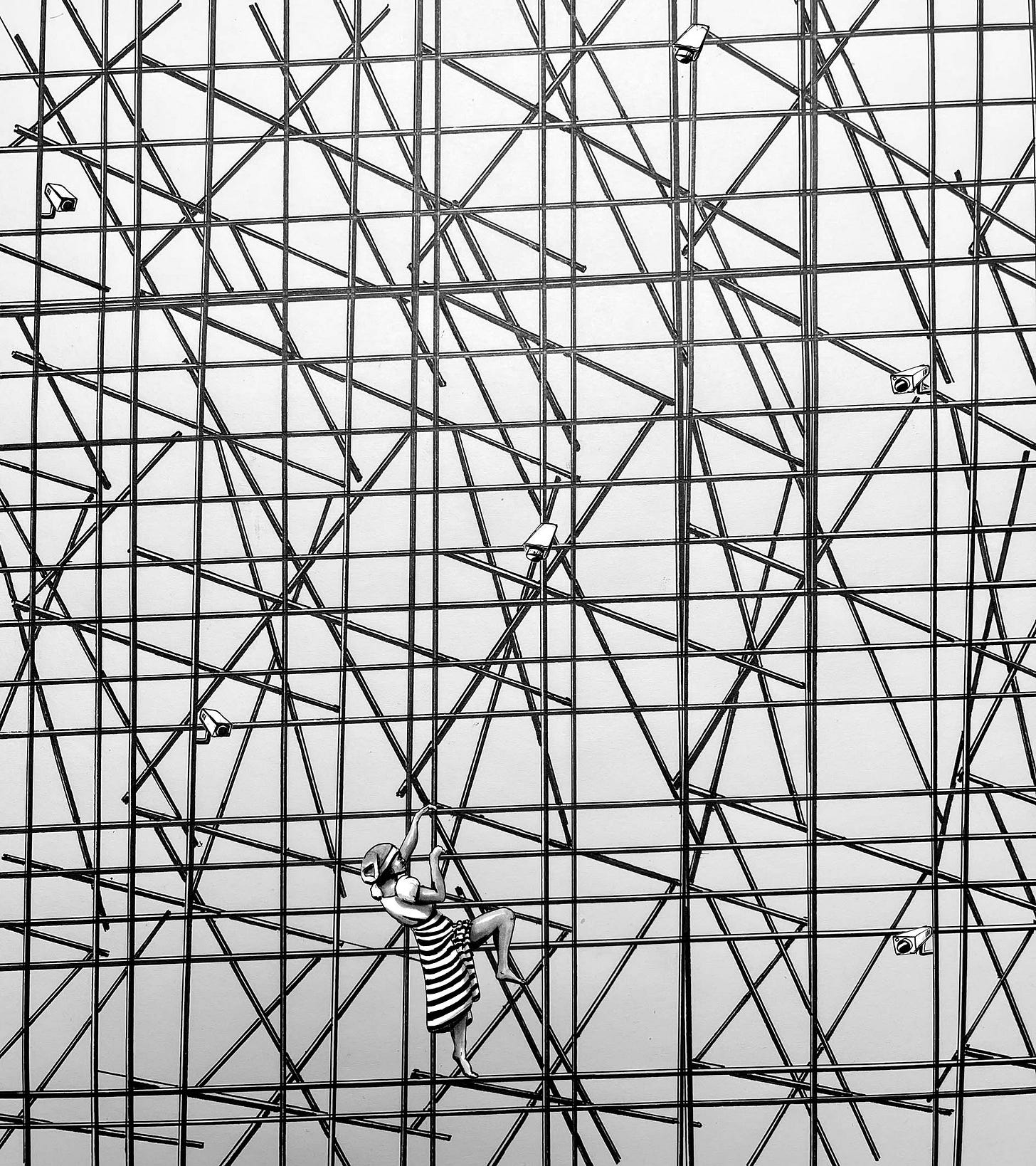

The report describes a vast, heavily surveilled warehouse floor near one of the city’s poorest areas, where mosquitoes buzz incessantly along long lines of functional desks. It is hot and chaotic, with loud music blaring at all hours of the day. Supervisors patrol the floor, and breaks are tightly monitored.

The data workers’ accounts sound more like a sweatshop than Silicon Valley.

At those desks, thousands of people do the work that is too expensive – or too boring, or too traumatic – to be done by the Big Tech firms themselves. T his work includes annotating images to help companies build their Artificial Intelligence (AI) models, making snap decisions on social media posts that might constitute hate speech or incitement to violence, and reviewing photographs and videos of extreme violence and child pornography.

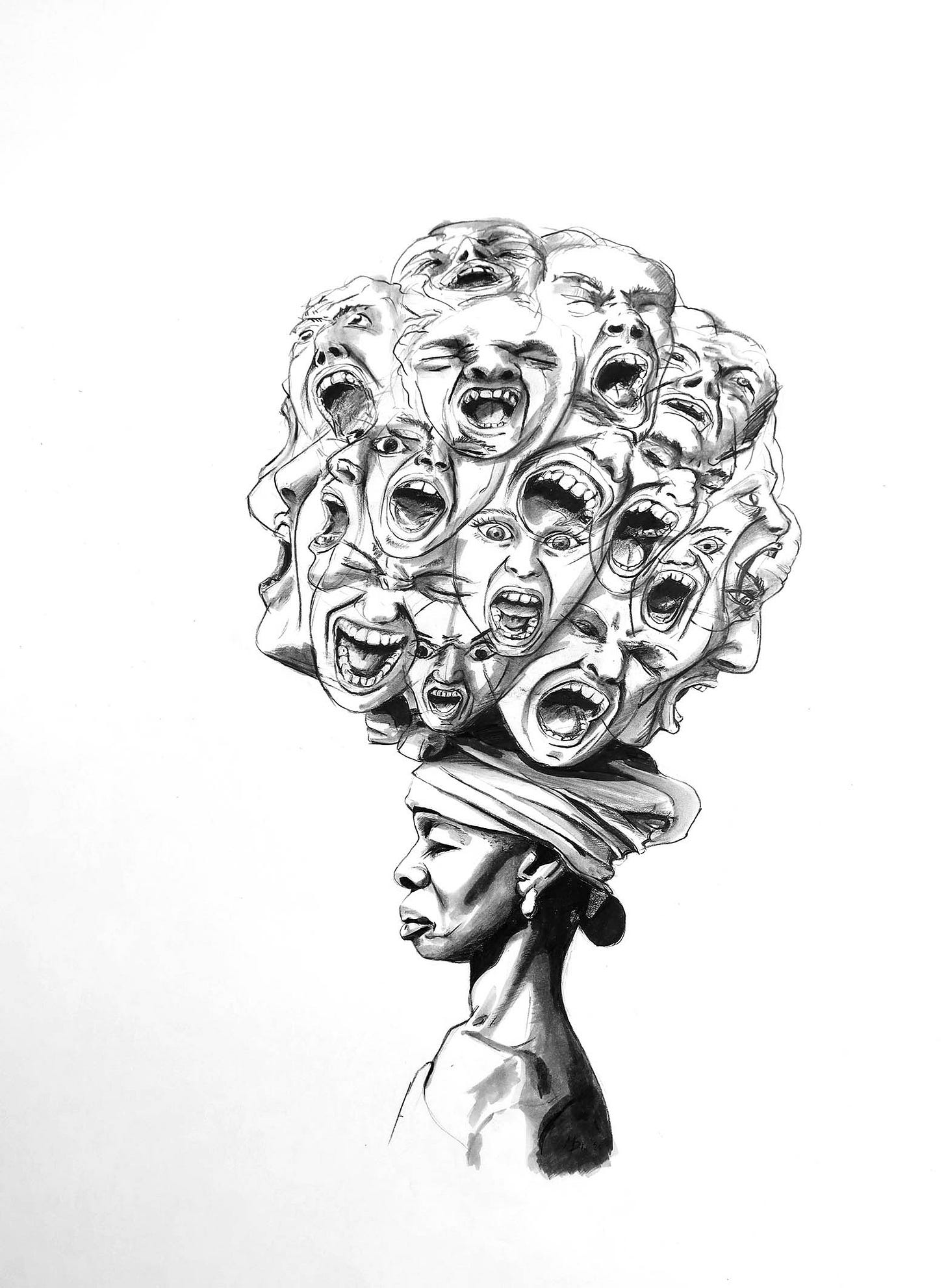

“It’s literally like a cinema for horror shows, where you go to see explicit horror scene content every day, except it’s in real life”, said Lethabo Lubanzi, a former Sama employee from South Africa. For this, data workers receive a monthly salary of 27,469 Kenyan shillings ($211).

The report details how data workers are exposed to content depicting extreme violence and sexual abuse. They are expected to review new content every 50 seconds over an eight-hour shift. Some developed drug and alcohol addictions, eating and sleep disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder.

When asked for comment, Sama said that the report contained “gross mischaracterisations and, in some cases, factual inaccuracies” and claimed a 68% employee satisfaction rating in a recent anonymised internal survey. “Sama offices are state of the art, and include thoughtful areas that address employee needs including prayer rooms, nursing rooms, game rooms, and a cafeteria…we strongly dispute the characterisation of Sama as a sweatshop.”

In August 2023, former content moderators in Nairobi sued Sama and Facebook over these allegedly poor working conditions. The case is ongoing.

High tech, low pay

In a forthcoming book, Feeding the Machine: The Hidden Human Labour Powering AI, British researchers conclude that millions of data workers are involved in the global AI industry. AI programs like ChatGPT, Copilot, and Llama could not function without these human inputs.

“Sophisticated software functions only through thousands of hours of lowpaid, menial labour — workers forced to work like robots in the hopes that AI will become more like a human,” they write.

The industry is entirely unregulated, and standards vary wildly between countries. Many data workers are employed remotely or as freelancers, making it difficult to access national labour protections – especially if something goes wrong. The Data Workers’ Inquiry report is one of the few existing attempts to bring together the experiences of data workers worldwide.

There are some common themes.

Much of the work is task-based and precarious. This means irregular hours and unpredictable pay. “We are ghosts to society, and I dare say we are cheap, disposable labour for the companies we have served for years without guarantees or protection,” said Oskarina Veronica Fuentes Anaya, a data worker in Venezuela.

She took on data work when Venezuela’s economy collapsed. That’s another theme: companies that solicit data work appear to target people in vulnerable countries and communities, where workers will work long hours for little pay, with no recourse if things go wrong. “Many annotators feel compelled to accept any available work, even if they are not fully available to complete it, due to the irregular nature of the projects and their pressing need for income,” said Roukaya al-Hammada, a Syrian refugee in Lebanon.

Al-Hammada said that initial enthusiasm for data work within the Syrian refugee community in Lebanon – who are not allowed to work in most industries within the country – quickly waned as the psychological impact of the work became more apparent. “While digital work to some extent offers an alternative and is undoubtedly beneficial, the scarcity of project opportunities and inadequate compensation prevents these vulnerable workers from achieving financial stability and psychological wellbeing,” she said.

As awareness grows of the negative impacts of data work, some efforts exist to create workers’ organisations for better conditions. Among the highest-profile of these was the 2023 formation of the African Content Moderators Union by more than 150 data workers in Nairobi. Many of these workers were employed by Sama. “Many data workers in the AI supply chain are exploited, and their work is never acknowledged. What is often overlooked is that there is no AI without us,” said Richard Mathenge, a union member.

There are, however, other workers. When Sama terminated its contract with Meta, the platform company hired a new provider in Kenya, Majorel.

Majorel reportedly pays its data workers even less.