Mauritius: A democracy in danger

Talk of supposed Mauritian stability is drowning out the country’s very real democratic challenges.

Harry Booluck

Mauritius is often described as one of Africa’s best democracies. After escaping military rule in the 1970s and 1980s, it developed a reputation for moderation, effective economic management and peaceful transfers of power. But ahead of elections, scheduled for November 2024, this is changing.

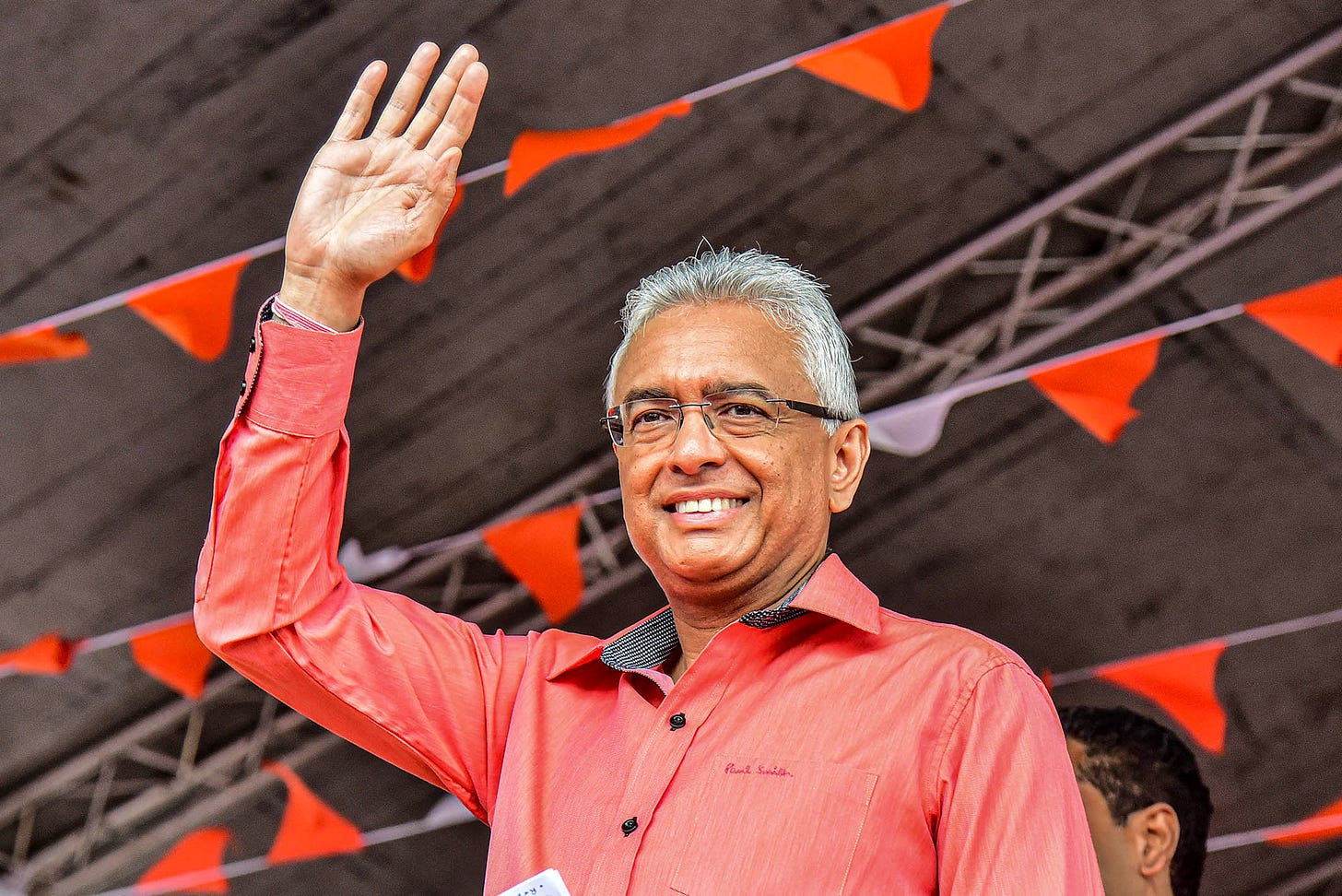

The current government, led by Prime Minister Pravind Kumar Jugnauth and his Militant Socialist Movement party, has gradually extended control over the country’s electoral system and wider society. Following allegations of election-rigging in 2019, the state has become increasingly intolerant of dissent, and introduced proposals for a new Information and Communication Technologies Authority with the power to monitor and decrypt social media content. Today, academics are afraid of speaking out lest it harm their careers; the same is true for many other critical voices.

There is also concern that the creation of a new police strike force had less to do with its mandate – increasing the capacity of the security forces to deal with drug traffickers – and more to do with enabling the government to harass opponents. In some cases, critics of the government have been arrested on “provisional charges”, and must remain in police custody despite the lack of a clear evidence that would justify prosecution.

As a result, while Freedom House – which measures the level of freedom around the world – still classifies Mauritius as a democracy, it also reports that the quality of civil liberties has fallen steadily since 2019. This trend is not lost on the Mauritian people: satisfaction with democracy fell to a low of just 32% in 2022, from 72% 10 years earlier.

Opposition parties have been vocal about these challenges. But the country’s reputation for stability means their worries are not being heard. Unless that changes, the 2024 elections could be the worst in the country’s history.