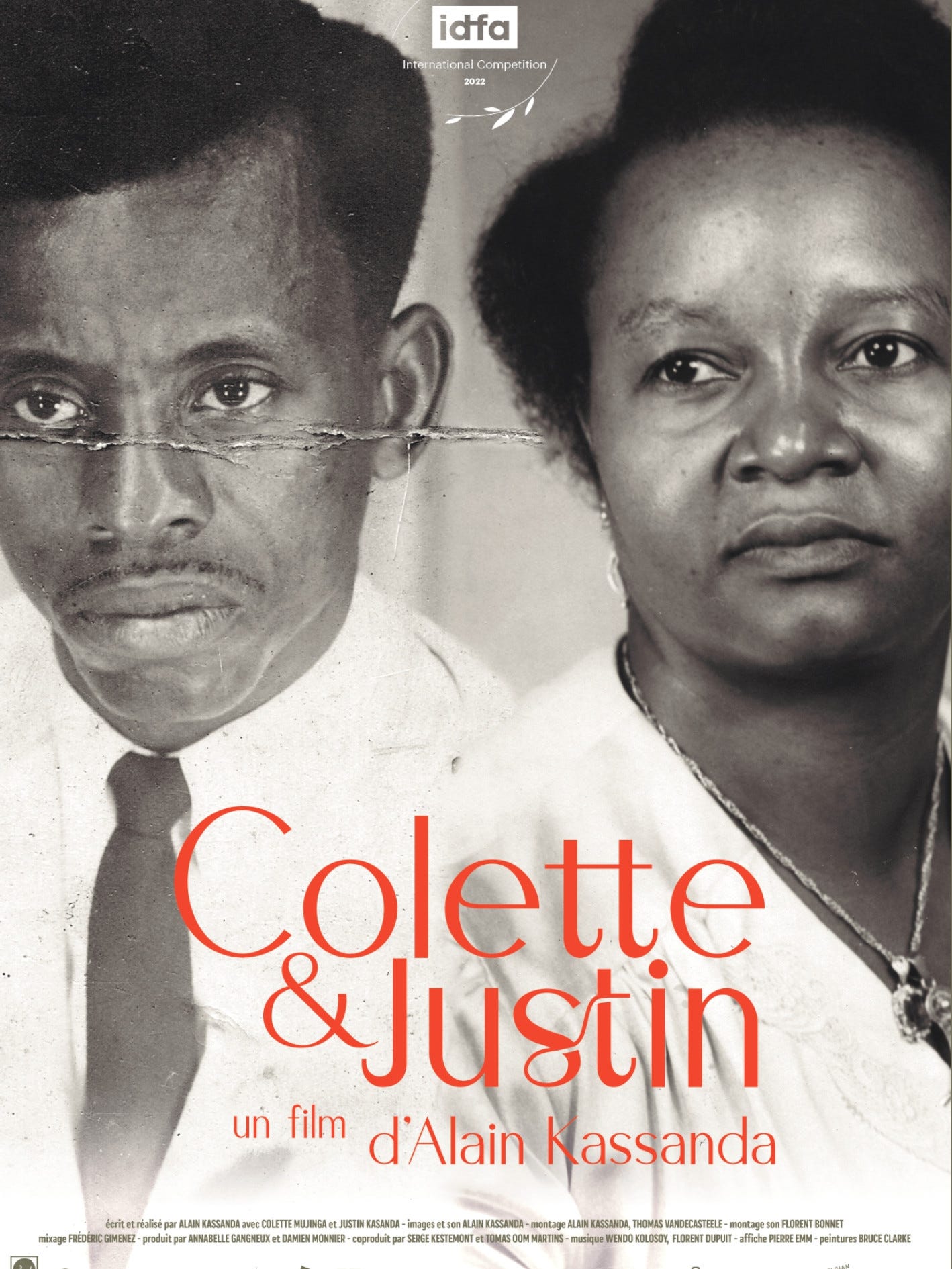

Inside the memories of people who lived Congolese history

History and recollection really are never black and white

When Alain Kassanda’s parents moved with him to France from the Democratic Republic of Congo at age 11, top of their mind was his education.

It was in 1991, amid an open-ended countrywide teacher’s strike in the DRC.

When he returned decades later, he got a re-education. In Colette et Justin, we tag along as Kassanda delves into Congolese history through the memories of grandparents, which he first captured on a borrowed camera and recorder.

“I didn’t plan on making a film, initially. I just wanted to capture their words because I knew that they were getting old,” Kassanda told The Continent.

Born in 1928 – two decades after the end of King Leopold II’s brutal plunder — Kassanda’s grandfather, Justin, had a widespanning memory of Congo’s formative years. “The more I learned through my grandfather’s stories, the more the idea of a film became present,” says Kassanda.

The result is Kassanda’s first full-length film – which Justin didn’t get to see as he died in 2018, during its production. Colette’s recollections give us granular insight into the colonial experience. The boys were taught in French and turned into well-oiled machines for colonial Belgians, while the girls were taught “home economics” in the regional language until the ages of 13 or 14.

“I didn’t plan on making a film, initially. I just wanted to capture their words because I knew that they were getting old.”

She directly witnessed the Belgian manufactured divisions between the Lulua and Baluba ethnic groups. Without Colette, an important part of Congo’s story would have been lost.

As Justin and Colette narrate their early years, the viewer is gripped by the film’s backdrop of archival footage from the colonial times. From videos of children sitting in missionary schools to photos of boys and men shackled with chains around their necks, the Belgians’ manipulation and brutality towards the people of Congo is on display.

Using this footage was a complicated choice for Kassanda. It was originally filmed for Belgian colonial propaganda. Belgian filmmakers who were enlisted to legitimise the colonial expedition rendered the Congolese people as objects to be watched– the uncivilised native.

Their audiences at home were meant to marvel at how powerful their country was in comparison. Yet in many cases, it’s the only visual documentation of those times.

Using this footage was a complicated choice for Kassanda. It was originally filmed for colonial propaganda. Yet, it’s the only visual documentation of those times

While Kassanda had little choice but to use the visual resources readily available, he contextualised them with his own voiceover narration. “The footage is used as cinematic support but also examined as a tool of propaganda,” Kassanda explains.

“I asked myself: ‘Why not help the audience create their own mental images using my reflections and commentary,’ ” he says. Kassanda’s voice became his own tool of colonial resistance, combatting myth and misrepresentation.

On complicated memories

Halfway into Colette et Justin, tension arises between Kassanda and his grandfather on the legacy of Patrice Lumumba. “This was the most difficult part of the documentary for me to film and to implement in the film,” he says.

For Kassanda and Justin, Lumumba’s Independence Day speech in June 1960 meant two different things. Kassanda argues that Lumumba’s speech was honest, brave and reaffirmed Congolese pride. Justin – at that time a civil servant – remembers it as “the speech of someone who didn’t know the difference between what should be said and what shouldn’t.”

Kassanda learns that his grandfather was not an ally to Lumumba, as he had assumed him to be, but was instead invested in the secession of South Kasai in 1960.

The interaction is a sharp reminder that history was more complicated and nuanced than we imagine.

“All of a sudden I had to reconcile two figures who are equally important in my eyes,” he says. “I needed to understand my grandfather’s story, not judge, and create a story that was not black and white.”

This deeply personal and political film was for Kassanda, and will be for many viewers, “a process of accepting history the way it was” – and not as we think it was or should have been.