How Wall Street fleeces African countries coming and going

Companies owned by global investment firms mine Africa and take the profits. Cash-strapped governments then borrow from the same firms at high interest.

Jaume Portell Caño & Lydia Namubiru

Life in Kédougou in Senegal is a paradox: poverty in the land of gold. Of the 17 tonnes of gold Senegal exported last year, more than half (9.13 tonnes) came from Kédougou’s Sabodala mine. Yet, in the same area, one barely gets the most basic of services.

“Gold exploitation leaves pollution for the population, but scarcely any benefits,” says Ahmad Dame Seck, the headteacher at the Dindefelo school in Kédougou.

He says that his students graduate (or drop out) into unemployment and struggle in the informal sector, or migrate to Europe, despite the money-making machine in the area.

The United Kingdom-based company which bought Sabodala mine in 2021, Endeavour Mining, has earned at least $598-million from it since.

In its latest financial statements, Endeavour Mining values the Senegalese mine as an asset worth more than $2.5-billion. Its other assets are mines in Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso and Mali, which it values at nearly $3-billion.

Endeavour Mining keeps 90% of the profits from its Senegalese operations – sharing them with its shareholders, of course. The Senegalese government takes the remaining 10%.

Inequitable resource extraction deals are one reason why Senegal struggles to raise enough revenue to run the country. When its coffers run dry, the government is driven to borrow from the international money markets. In a bitter irony, it often turns to the very same firms that are taking the lion’s share of the revenue from the Senegalese gold mining industry.

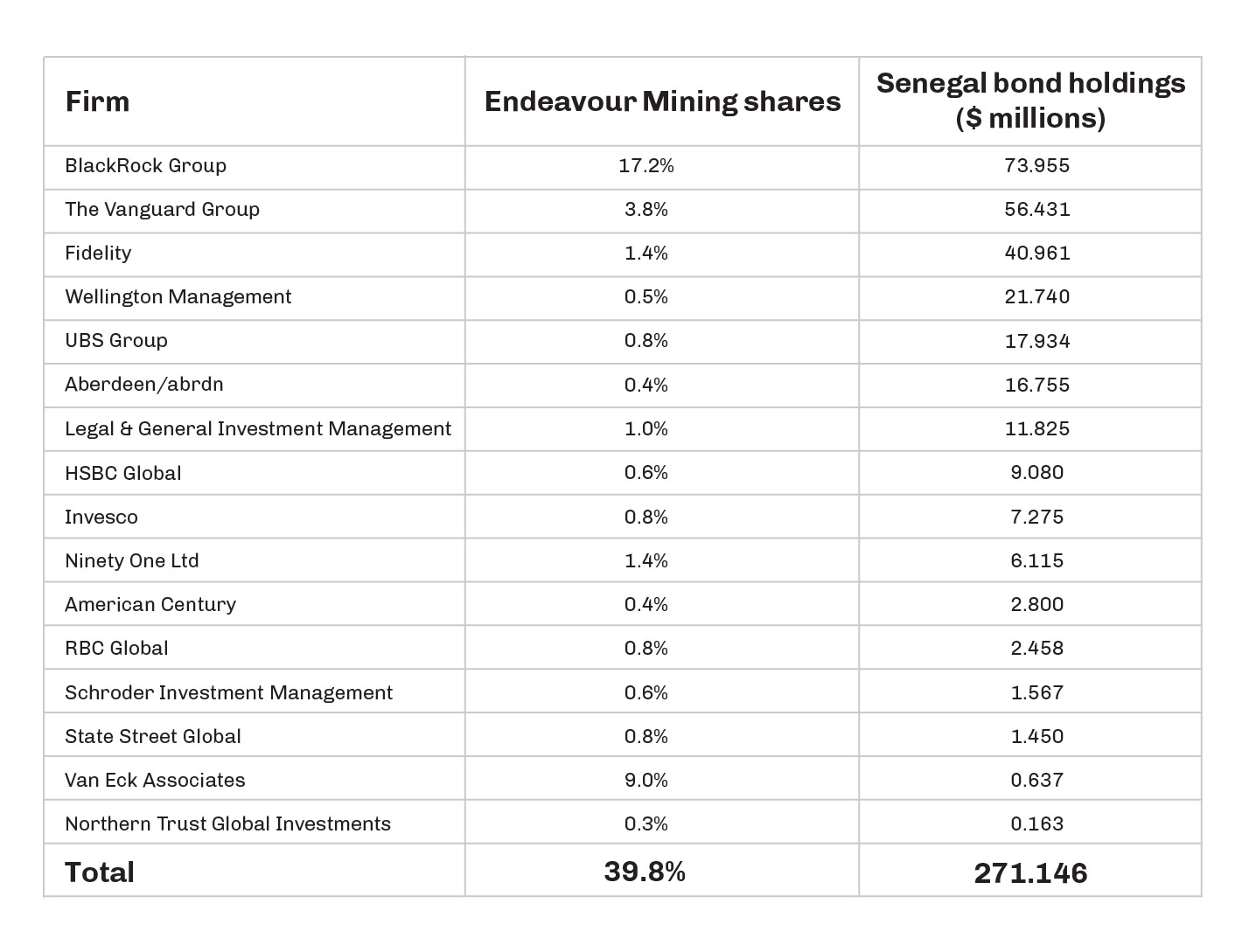

New and exclusive analysis by The Continent shows that 40% of the shares in Endeavour Mining are owned by 17 investment firms that are also trading in Senegal’s sovereign bonds. The Senegalese government owes them more than $271-million.

When Senegal pays annual interests on those bonds – up to 7.75% depending on the bond note – the firms that are already taking much of the money from Senegalese gold, earn from the country being cash-strapped. This dynamic – lining pockets to borrow from them – repeats itself in many countries. African states have issued dozens of international bonds, borrowing at least $84-billion from global investment firms like BlackRock, Fidelity, HSBC, Schwab, etc.

These firms also often own millions’ worth of shares in the multinational companies extracting local resources.

The worst kind of national debt

Private creditors’ loans, of which bonds are but one example, tend to be the harshest kind of national debt to accumulate – interest rates are high, there are no grace periods, and lenders listen only to the markets. When states default on interest payments, economic chaos ensues.

Zambia, Ghana and Ethiopia failed to pay interest on their bonds, after the Covid pandemic and other economic shocks undercut the growth their borrowed money was projected to spur.

These defaults pushed their leaders to turn to the International Monetary Fund for bailouts, whose requirements include hard-nosed economic policy changes like floating national currencies and hiking taxes. The pain of some of these policy changes has driven citizens to the streets in protests that are sometimes fatal, and always costly to local economies.

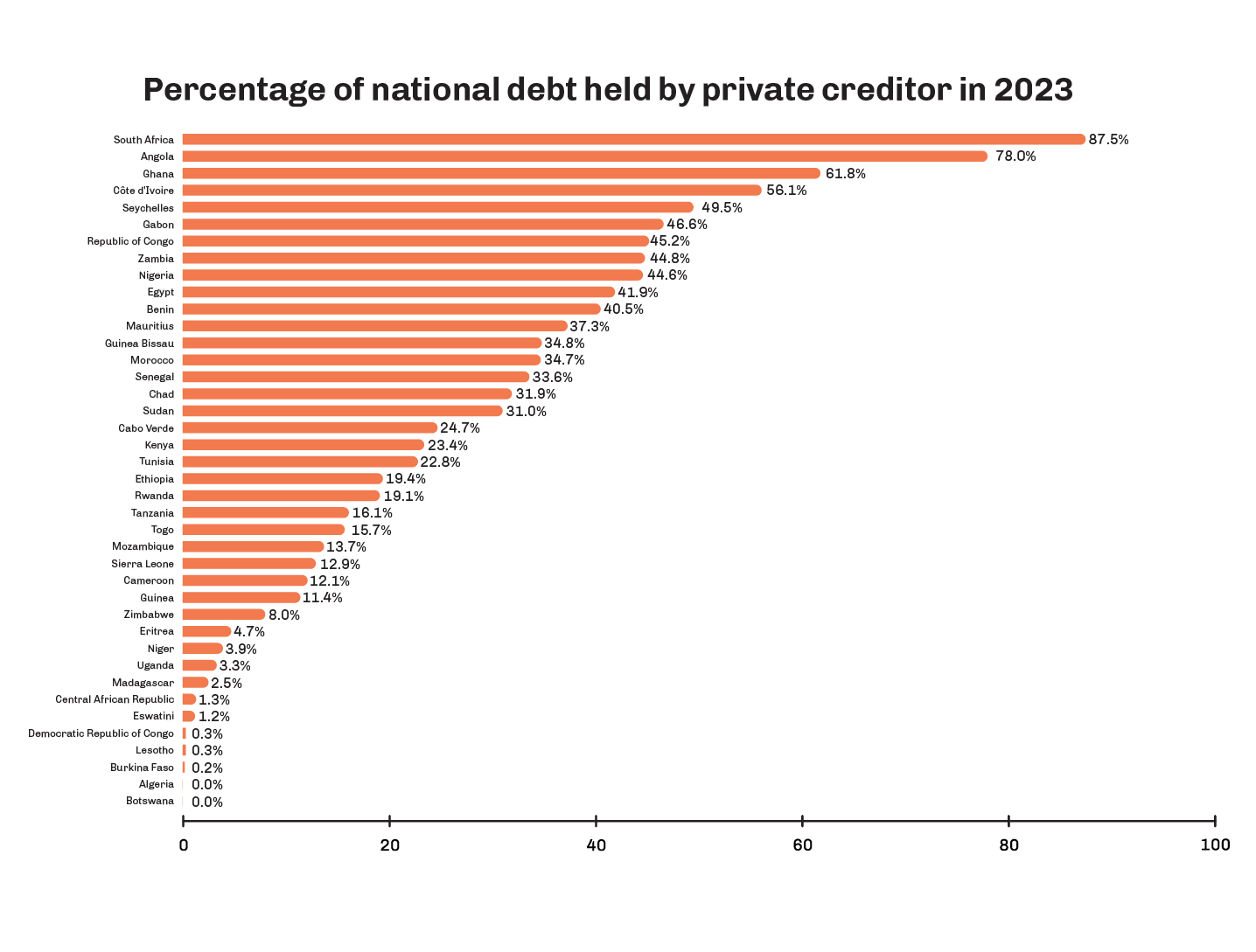

Yet African governments have continued to dig deeper into this kind of debt. According to data from the United Nations Trade and Development agency, African governments owed more than $777-billion to private creditors by the end of 2023. Private creditors now hold about 44% of Africa’s national foreign debt, compared to 30% in 2010.

It’s not an evenly distributed risk. Middle income countries are often ineligible for low-interest lending from institutions like the World Bank and turn to the private creditors more often. But enthusiasm for that risky path is not equal. In South Africa and Angola, private creditor loans make up 88% and 78% of national debt. In Algeria and Botswana, it’s negligible, even though their economic health is comparable.

Like government, like citizen

Issaga Diallo does not know the details of global capitalism and its circular extraction. But he knows that his own fortune will not come out of the fancy Sabodala mine that is plush with global money. He works as an artisanal miner in Bantakokouta, near Kédougou, where a gram of gold can earn up to $50, $20 less than the global market price.

The Bantakokouta village extends only about two kilometres beyond a mountain of displaced rocks that surround the gold pits in which artisanal miners dig. Diallo has lived there for almost eight years now, after dropping out of school in 2016.

Every day, he pays for fuel to run a generator for his equipment, but he sometimes works for months without finding any gold. When that happens, he accumulates loans, promising to pay creditors back when he finds gold – much like national leaders do when they issue bonds on the global money markets.

In the long run, if Diallo is lucky more often than he is not, he hopes he will make enough money to start a business in the more urban Kédougou. On his phone, he likes to watch videos of miners who discover more than 100 grams – this keeps his hopes alive.

In the long term, if the Senegalese government is luckier than Zambia, Ghana and Ethiopia have been, it will make enough money to diligently pay bond interests until its own resource sector meaningfully pays into the domestic coffers. In the short term, however, the people profiting from that sector, and from those interest payments, are not your average Senegalese citizen.