How to fund African development – and how not to

Aid is dead. Grandma is not. But taking her pension to build a road might kill her.

Lydia Namubiru

On Monday, when world leaders meet in Seville, Spain for the fourth International Conference on Financing for Development, it will be summer outside but winter in the room, particularly for delegates from aid dependent economies. “The world as we know it has changed – for aid, trade and development,” as Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the chairperson of the World Trade Organisation, put it early this month.

The United States, which used to fund nearly 30% of global aid, is withholding assistance that is potentially worth in excess of $8-billion. Meanwhile, member states of the European Union have reduced their official development assistance by 8.6%.

And not all of that goes to where it is needed most, anyway: about 13% of the money labelled foreign aid last year by members of the Development Aid Committee, a collective of some of the world’s largest aid providers, was actually domestic spending on refugees. This shrinking and relabelling is unlikely to stop now, as world politics takes a sharp turn inward and away from multilateralism.

“It may not be the end of aid but it certainly is the end of the sums and quantities we’ve been used to. It may come back but not for a very, very long time – and probably with new governance mechanisms,” said renowned Cameroonian economist Vera Songwe in an interview with The Continent.

“We’ve transitioned into a transactional world, which signals to Africa that we need to pull ourselves up by our bootstraps,” Ghana’s President John Mahama said at the annual meetings of the African Development Bank (AfDB), where delegates learned that the US was reconsidering its $555-million commitment to the lender.

Raiding retirement

What are these bootstraps? For some, the lowest hanging fruit is workers’ savings – in the form of pension funds. “Pension funds are underused in financing Africa’s infrastructure,” says a mid-May op-ed in Devex, a trade publication of the aid industry. “Billions in domestic capital to drive Africa’s development idling in pension funds,” says a post published on the AfDB website in late May.

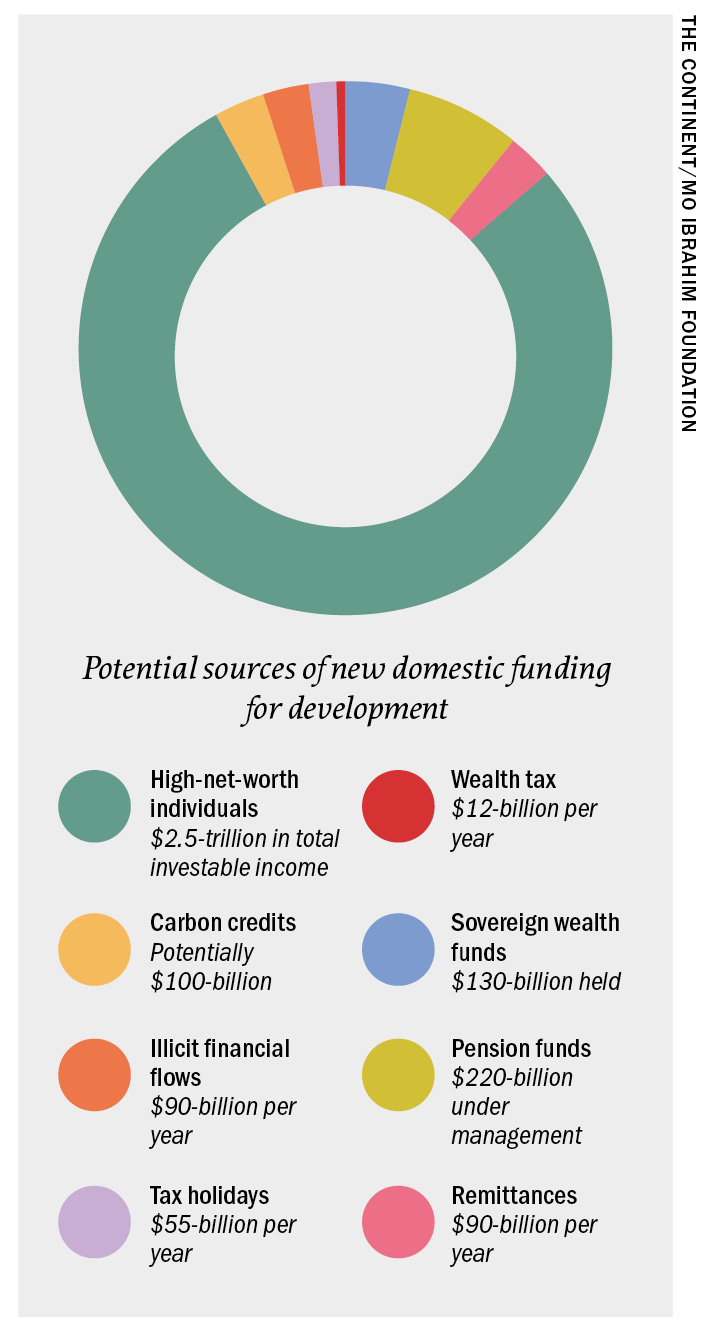

“African pension funds stand at almost $220-billion and represent the largest source of investable capital,” says the Funding the Africa we want report, published by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, in early June.

Changing AfDB’s governance rules to bring in capital from non-traditional sources “could open the way for African pension funds to get more involved” in the Africa Development Fund, which lends to governments at low or no interest, a fellow at the Atlantic Council told African Business magazine last week.

“Pension funds are underused in financing Africa’s infrastructure” says an op-ed in Devex, a trade publication of the aid industry.

Muted in this fast rolling conversation is the fact that the public goods for which aid was used – like healthcare, education and infrastructure – are not known for their for profitability. Pension funds, meanwhile, are supposed to protect their members’ savings while keeping up with inflation. Pension funds cannot afford to lose money.

“We need to be honest. Pension funds can’t go to just any type of infrastructure asset. Building a road is not going to work for a pension fund,” says Heike Harmgart, managing director for sub-Saharan Africa at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Africa’s pension savings are already thin: according to a United Nations study, less than 10% of African workers are covered by pension schemes. And, as talk of “idling” billions suggests, taking money from pension schemes directly into public projects would be a dramatic change in how fund managers keep and build worker’s savings. It would require entirely new regulations that aren’t being proposed at the same speed.

“Let’s remember that pensions are individual citizens’ resources and so not free resources for use. If we are going to use them for development, then we have to make sure that the systems within which we are using them are robust,” says Songwe. “You don’t want somebody who has spent 40 years of their life working and saving to not have their resources when they need them because they have been poorly spent, or through weak governance processes were used for investments that are not able to pay a return.”

That’s not to dismiss the option. But proponents of the idea would have to allow for time for writing new rules that safeguard workers as investors in public projects, and for the sector to create options that are nearly as safe as the treasury bills that pension funds favour.

Some projects are starting to figure out what the latter could look like. The Benban Solar Park in Egypt was built with money from development banks, but issued a post-construction bond to raise operational funding. With a longterm agreement from the government to buy its electricity, pension funds bought in. “We need to create more things like that. We have to restructure it in such a way that you are not putting too much risk on pension funds,” says Hargmat.

Tax the rich

There are other ways that governments can raise money for development, even in a “post-aid” world: plugging holes like illicit financial flows; runaway debt service; under-taxing the wealthy; taxing only a small portion of residents; and the flight of local capital to friendlier places.

By some estimates, African billionaires and millionaires (who are expected to number more than 223,000 individuals by 2030), already have $2.5-trillion in investable income. That is far more than is held by pension funds. According to the Mo Ibrahim Foundation report, a special tax on some of their assets – those valued at more than $5-million – could generate $12-billion a year.

Successfully pushing for debt relief at the multilateral level could also retain some of the $103-billion flowing out of Africa every year that goes to pay lenders. Ending tax holidays at home could save up to $55-billion, and tackling capital flight would retain up to $90-billion a year, the report says.

There are more pots to tap. Carbon markets could earn Africa $100-billion by 2050, and national sovereign wealth funds are holding $130-billion that could be invested in these projects.

Whichever route is taken, the money will only meet the gap if national leaders tighten how efficiently it’s used, says Songwe. “If you need 100 dollars to build a power plant, and the next person needs 10, then 90 have been wasted. We must do more to manage our resources.”

Oof that light green slice! 😅 Further detail in the same Mo Ibrahim Foundation report puts 27% of those individuals in South Africa, followed by Egypt, Nigeria, Kenya, and Morocco