Haiti is still being punished for overthrowing slave-owners

Kenya’s proposed intervention should not ignore the Caribbean island nation’s complex history.

Simon Allison

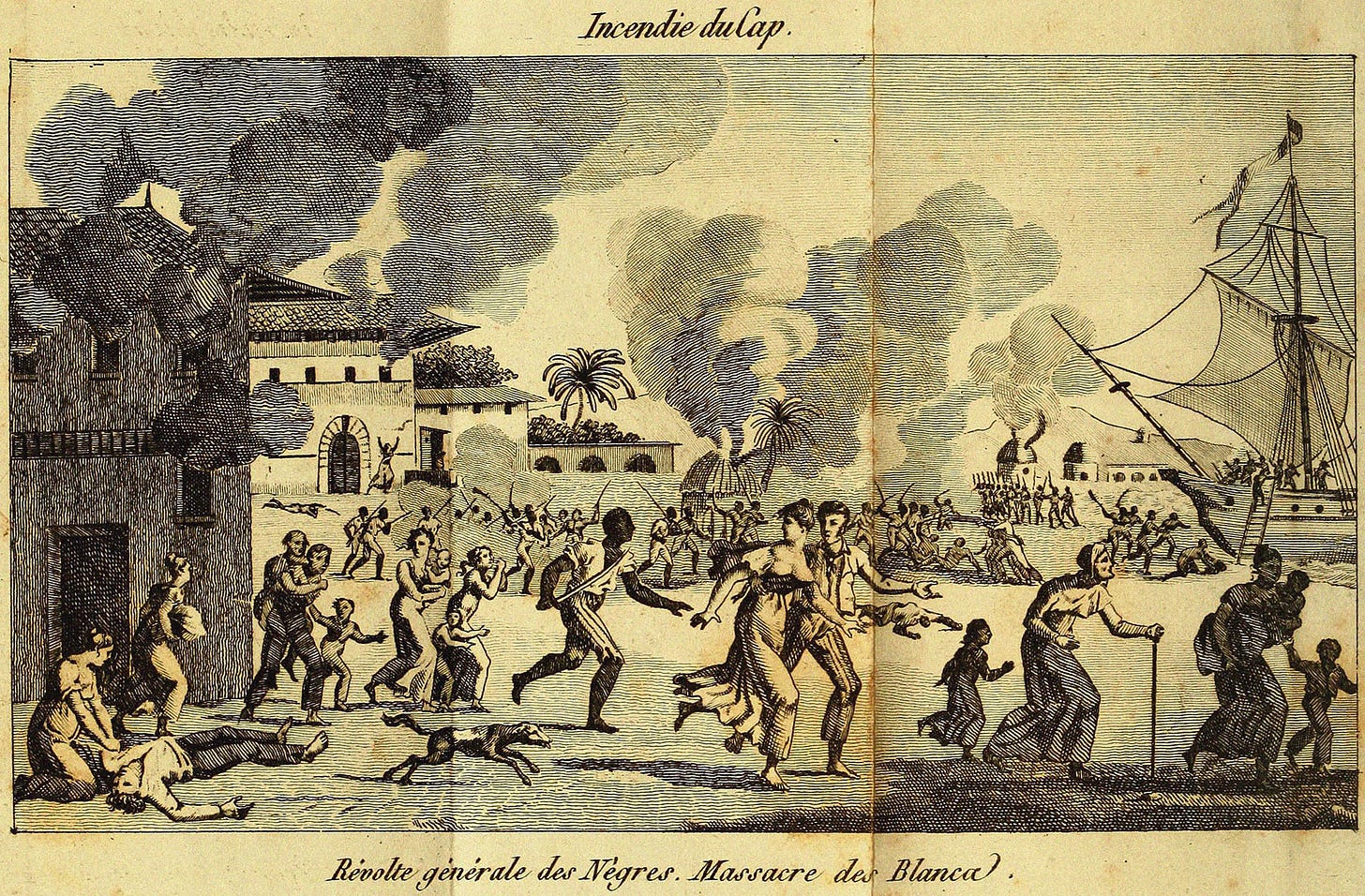

Howard French, the author of Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans and the Making of the Modern World, describes the Haitian Revolution of 1792 as “one of the most remarkable stories of liberation that we have as a species: the largest revolt of enslaved people in human history, and the only one known to have produced a free state”.

That state, occupying about a third of the Caribbean island of Saint-Domingue – once the most lucrative of all the French colonies – was named Haiti. It successfully defied the collective might of the British, Spanish and French armies, becoming the first independent, black-led republic in the western hemisphere.

Unable to defeat Haiti militarily, colonial powers devised another punishment. France imposed an “indemnity” of 150-million francs – a staggeringly large sum for the time – saying that it needed to compensate slave-owners for their lost land. France also sought to make an example of Haiti, to discourage rebellions elsewhere.

Haiti’s new rulers, wary of being invaded again, agreed to pay. The country has been paying ever since.

In a 2022 investigation, the New York Times described “a debt so large, and so lasting, that it would help cement Haiti’s path to poverty and underdevelopment”.

Its reporters estimated that the “indemnity” cost Haiti $122-billion in lost revenue and missed economic opportunities. “Haiti became the first and only country where the descendants of enslaved people paid the families of their former masters for generations,” the investigation concluded.

The massive debt – later bought out by an American firm, during a decades-long occupation by the United States, which continued to extract enormous revenues from the country – has made it impossible for Haiti to prosper. “This hobbled Haiti’s chances of developing viable financial and democratic institutions for much of the 19th and 20th centuries,” wrote Malick W. Ghachem, a professor of history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in Foreign Policy magazine.

There is a direct link between this punitive debt burden and the near-total breakdown of the rule of law in Haiti today, argues Ghachem. “Pervasive state-sanctioned gang activity is just the most visible reflection of the primary, though under-recognised, driver of Haiti’s catastrophe: the country’s broken monetary system, which is a legacy of its colonial past.”

It was in an effort to address this catastrophe that Prime Minister Ariel Henry travelled to Nairobi last week. He is the country’s de facto leader after the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in 2021, but he does not even control its capital city: some 80% of Port-au-Prince is thought to be run by heavily-armed gangs. And while Henry was in Nairobi, the gangs struck again: this time, attacking two major prisons and releasing nearly 4,000 prisoners. Fierce street battles between various gangs and the police continued throughout this week, and on Wednesday the international airport was attacked.

In Nairobi, Henry signed a deal with Kenyan President William Ruto to send 1,000 Kenyan policemen to quell the violence in Haiti. This is being underwritten by the US to the tune of $200-million (“thus sparing the United States from spilling any of its own blood in whatever battles may be upcoming,” said journalist Amy Wilentz in The Nation).

Benin has also offered to deploy 2,000 soldiers.

Assuming they are eventually deployed (this is far from certain: one Kenyan court has already declared the deal illegal), it is unclear what difference, if any, a few thousand policemen with no local knowledge or context will make. There are around 200 gangs operating in the country: “So that makes 15 men, if all the countries sign up, to control each gang,” observed Wilentz.

It would be difficult, dangerous work – and serves only to distract from the urgent need to free Haiti from its economic shackles. “A concerted international campaign to support Haiti’s financial sovereignty is the real intervention that Haiti needs – and possibly the only one,” said Ghachem.

The Haitian crisis has its roots in the enslavement of black Africans. It is a bitter irony that the very same western nations responsible now propose a solution that involves paying to put black Africans in danger – while refusing to take any responsibility for the historical injustices which led the country to this point.