Global rankings don’t give African universities enough credit

We need to find better ways of measuring the impact of our tertiary institutions.

Ten years ago, only four African universities featured in the global rankings of the United Kingdom-based Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings. That figure has since risen to 97.

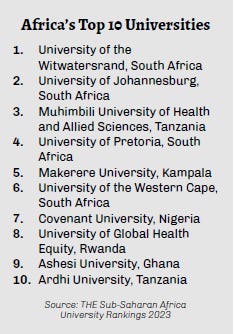

In response to the growing significance of tertiary education on this continent, earlier this year THE launched its Sub-Saharan Africa University Rankings, which includes 88 universities across 20 countries on the continent.

Global rankings are influential in shaping a university’s reputation. But not everyone is convinced of the need for these rankings, which tend to concentrate power and prestige among universities in the Global North, maintaining and reproducing an unequal status quo.

“The main criteria and methods used in global university rankings reflect perspectives and standards that are biased towards wealthier, older, larger, and more research-intensive universities in the Global North,” says David McCoy, a research lead and professor at United Nations University. “Crucially, none of the major rankings apply methods that control for the resources available to a university or that adjust for challenging and unstable social and political contexts, for example.”

Additionally, universities can only gain a higher placement if other universities lose theirs. This system of winners and losers negates the notion that standards can rise across the board, incorrectly implying a finite amount of good quality education and research that universities must compete over.

“Such an imagined zero-sum game institutionalises and accentuates inequality within the higher education sector at the expense of promoting high quality education universally,” a report from the United Nations University explains. Already, according to THE, Africa’s tertiary education is further hindered by competition from outside the continent for academic talent.

It is important to remember that the justification for Africa’s universities is strongly anchored in post-independence nation-building. “At independence, every country needed to show its flag, national anthem, national currency, and national university as proof that the country had indeed become independent,” Mahmood Mamdani, the Ugandan scholar once noted. Universities were expected to train the professionals needed in the expanding public service.

This link to national development incentivised governments to fund universities, making them more accessible. Of the top 10 universities in the THE Africa rankings, seven are public and their median annual tuition is under $1,200, compared to about $2,300 in private nonprofit universities and $4,000 in for-profit universities in that tier.

The public service values and justifications for African higher education are not easily represented in global lists and could be lost when institutions prioritise the rankings game.

An awkward colonial inheritance also persists. Universities across Anglophone Africa were modelled, structurally and philosophically, on England’s “Oxbridge” universities; some were originally built to support British colonial policies. They have much decolonising ground to cover in moving away from the western value judgements embedded in global rankings.

So where should African universities focus? Given developmental challenges on the continent, perhaps something more radical than what exists now.

The World Bank has consistently asserted that Africa needs more PhDs – innovative researchers who will diagnose challenges and produce solutions that are appropriate to their context.

But here again we must be sceptical about transplanting western models, warns Eric Fredua-Kwarteng, a Ghanaian education policy scholar. Producing PhD holders whose overriding career ambition is to teach and research within Ivory Towers, as the western model often does, is not suitable for Africa.

Fredua-Kwarteng says that Africa must design its PhD models to produce researchers who will teach and produce new knowledge – but also make policy, participate in entrepreneurship and run economies.

A ranking that captures efforts in that direction might just be worth paying attention to.