Germany has learnt nothing from its terrible history

Germany, despite its public shows of remorse, has learnt nothing from its history in Namibia

Henning Melber

On 12 January 1904, the Ovaherero paramount chief, Samuel Maharero, ordered his people to rise up against the colonisers who had occupied their land and renamed it “German South West Africa”.

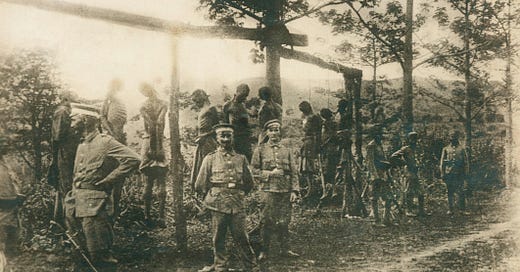

In response, the German military commander Lothar von Trotha issued an extermination order, prompting Nama communities, led by Hendrik Witbooi and Jacob Marengo, to join the resistance. Von Trotha’s forces brutally implemented their extermination orders. By 1908, an estimated 80% of the Ovaherero had been wiped out. So too had 40% of the Nama. The mortality rate was especially high among women and children who were forced into concentration camps. Damara and San communities – considered collateral damage – suffered a similar fate.

This was the first genocide of the 20th century. It took more than a century for Germany to even acknowledge the crimes, and only in 2021 did the European country offer any form of apology. That apology came with caveats, however, to prevent legal culpability and head off calls for reparations.

Nonetheless, under enormous diplomatic pressure, it was preliminarily accepted by the Namibian government, whose special envoy initialled it in a “joint declaration” with Germany.

Germany thought that it had drawn a line under this ugly chapter in its history.

It was wrong.

The declaration was rejected by most parties in Namibia’s National Assembly, and by the main agencies of the descendants of genocide victims – who were excluded from the negotiating table. The Herero paramount chief, Vekuii Rukoro, termed it “an insult”.

No reparations accompanied the apology, and no serious effort has been made to return land to the communities dispossessed during the genocide – this land remains overwhelmingly in the hands of white settlers.

Even the Namibian government was unsatisfied, and was pushing to renegotiate the terms of the joint declaration before ratifying it.

Then came Israel’s war in Gaza – and Germany’s vociferous support for a military action which has so far claimed the lives of at least 26,000 people, mostly civilians. The war has been waged with such brutality that South Africa officially accused Israel of committing genocide in a case at the International Court of Justice.

On 12 January 2024 – 120 years, to the day, since the beginning of the war that precipitated Germany’s genocide in Namibia – Germany announced that it would intervene in the court case in The Hague: not to protect civilians from further attacks, but instead to defend Israel’s right to “defend itself ” after the attacks by Hamas on 7 October last year, in which approximately 1,200 people were killed and 240 people taken hostage.

Germany, despite its public shows of remorse, has learnt nothing from its history – as Namibia’s President Hage Geingob was quick to point out, in an uncharacteristically blunt outburst:

“The German government is yet to fully atone for the genocide it committed on Namibian soil … Germany cannot morally express commitment to the United Nations convention against genocide, including atonement for the genocide in Namibia, whilst supporting the equivalent of a holocaust and genocide in Gaza.”

Geingob’s strongly-worded reaction reflects the feelings of many Namibians.

These feelings have their roots in the decades of discrimination and racism inflicted on Namibia by Germany – which, symbolic moral gestures aside, Germany has made no real effort to redress.

In stark contrast, Germany has turned its feelings of guilt over the Holocaust into uncritical loyalty to an Israeli government.

Notwithstanding the horrific massacres committed by Hamas on 7 October, one evil crime cannot excuse another evil crime. Two wrongs do not make a right.

“Never again” should mean never again.

Instead, after committing two genocides in the 20th century, Germany risks facilitating another one in this century. For Namibia, ratifying the joint declaration should no longer be an option.

But this may, perhaps, be the moment to pressure Germany further to make real amends for its past mistakes – and, this time, to include the communities of victims in the negotiations; and to make sure that substantive reparations are firmly on the table.