French foreign lesions: This reckoning is overdue

Colonial atrocities are finally catching up to Paris, and Macron’s government is too weak to put up a fight.

Beverly Ochieng in Dakar

On Thursday last week, French President Emmanuel Macron’s flailing government was hit with a one-two punch.

“It is time for Chad to assert its sovereignty,” said that country’s foreign minister, Abderaman Koulamallah, as he declared an end to decades of military co-operation with France.

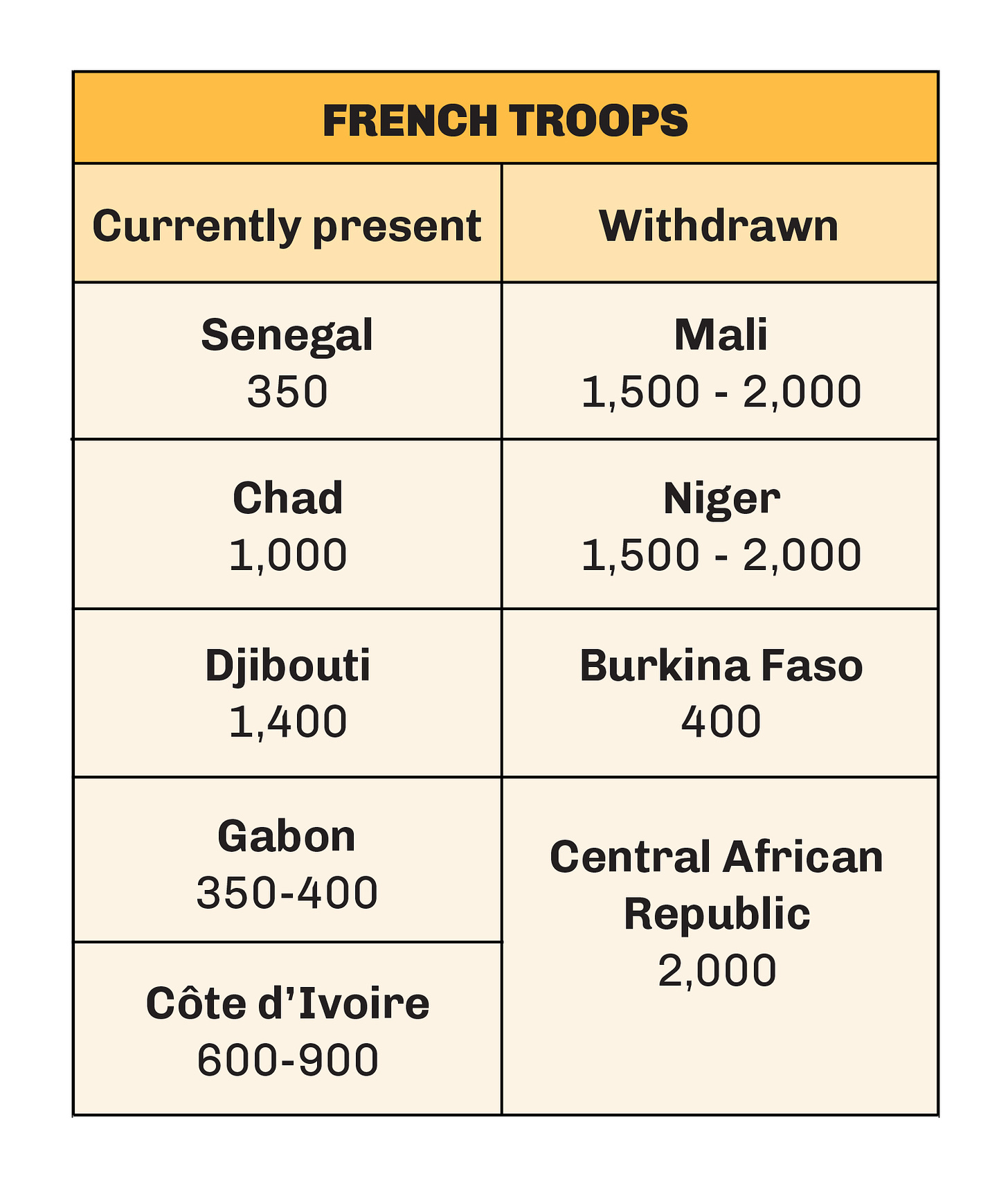

Chad has ordered France to withdraw the 1,000-odd French soldiers still stationed in the country.

A few thousand kilometres away, at almost the same time, Senegal’s President Bassirou Diomaye Faye was telling French media that the presence of some 350 French troops in Dakar “is incompatible with our national sovereignty”, and that they would soon be sent home.

It’s unlikely the two African governments co-ordinated their announcements. Nonetheless, they landed with a bang in Paris.

“The slap in the face is all the more stinging for being twofold,” wrote Le Monde, a French newspaper, in an editorial. “This is another serious setback.”

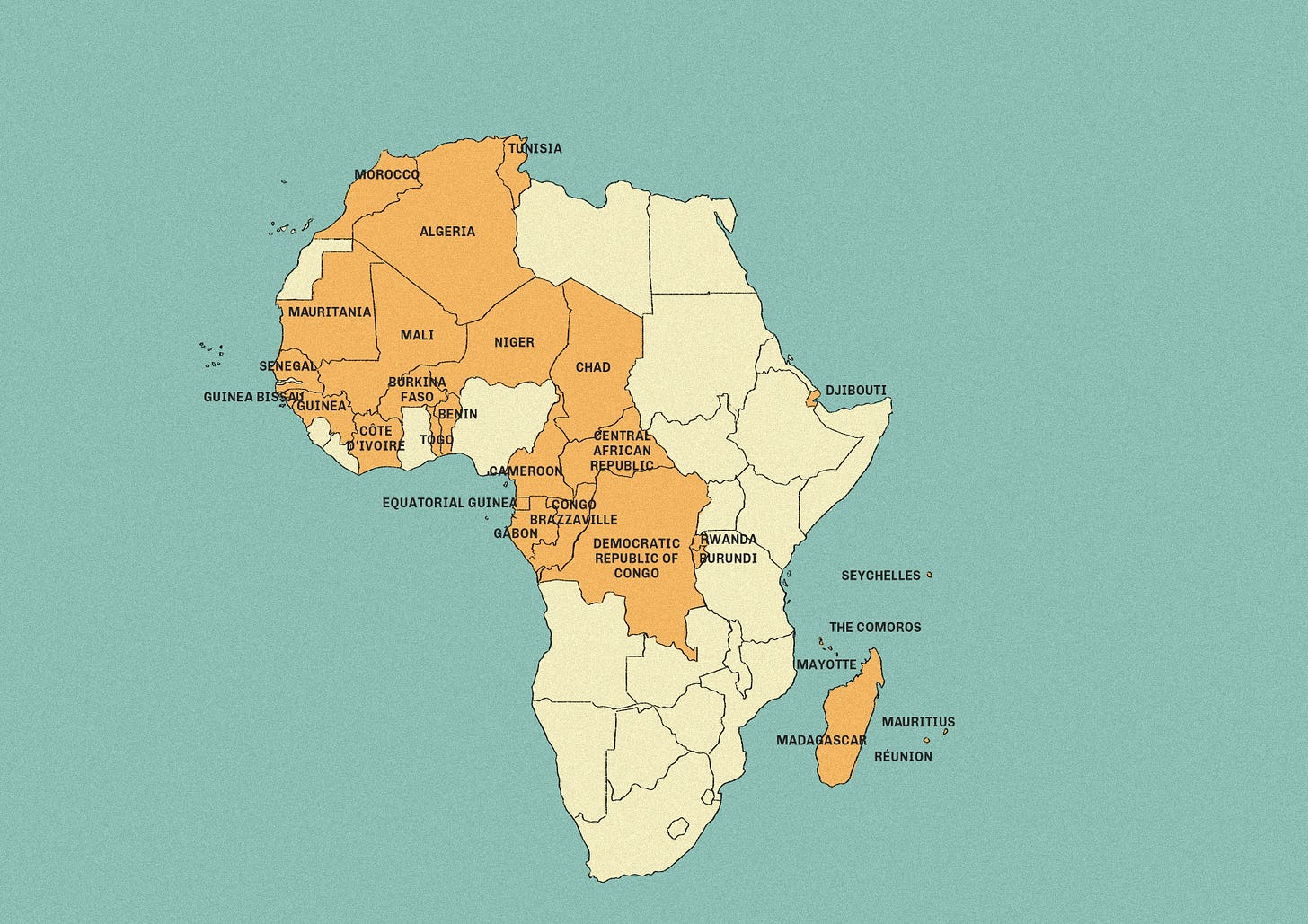

In recent years, there have been several such setbacks for the former colonial ruler. France has, after losing most of its colonies in the 1960s, operated a vast network of military bases across its former African territory. But that network is shrinking fast.

In 2022, the junta in Mali ordered the immediate withdrawal of French troops, as did the government of the Central African Republic. Coup leaders in Burkina Faso and Niger followed suit the next year. Now it’s Chad and Senegal’s turn to demand an end to France’s military presence.

Le Monde, echoing other French commentators, explained these “setbacks” in the context of global geopolitics.

“The opposition to the French military presence is based on the same context: its rejection by a large part of the public, particularly young people, and the many offers of service (American, but also Russian, Chinese, Turkish, Saudi and Israeli) now being made to African heads of state,” the newspaper concluded.

In Chad, there may be some merit to this analysis. From a military perspective, the country is vital to French interests, functioning as the army’s logistical hub for the Sahel region – “an aircraft carrier in the desert”, as it is sometimes described.

France has a long history of intervening in the internal politics of the country, playing a key role in bringing first Hissène Habré (who ruled from 1982-1990) to power, then later Mahamat Déby’s father, Idriss Déby Itno (1990-2021).

Déby junior, however, has been dissatisfied with the level of French co-operation in fighting multiple insurgencies – even accusing France of withholding intelligence and air support at crucial moments.

At the same time, he has been courting other allies, notably Russia and the United Arab Emirates.

He has also struck up an unlikely friendship with Hungary’s President Viktor Orbán, who is sending 200 soldiers in the new year to train local forces, and has promised $200-million in aid.

Senegal’s position is not so easily explained by superpower politicking, however.

There is little evidence of Russian interference, beyond regular diplomacy, and the timing of Faye’s announcement suggests a different motivation – one rooted in a terrible crime that happened eight decades ago.

Remembering a massacre

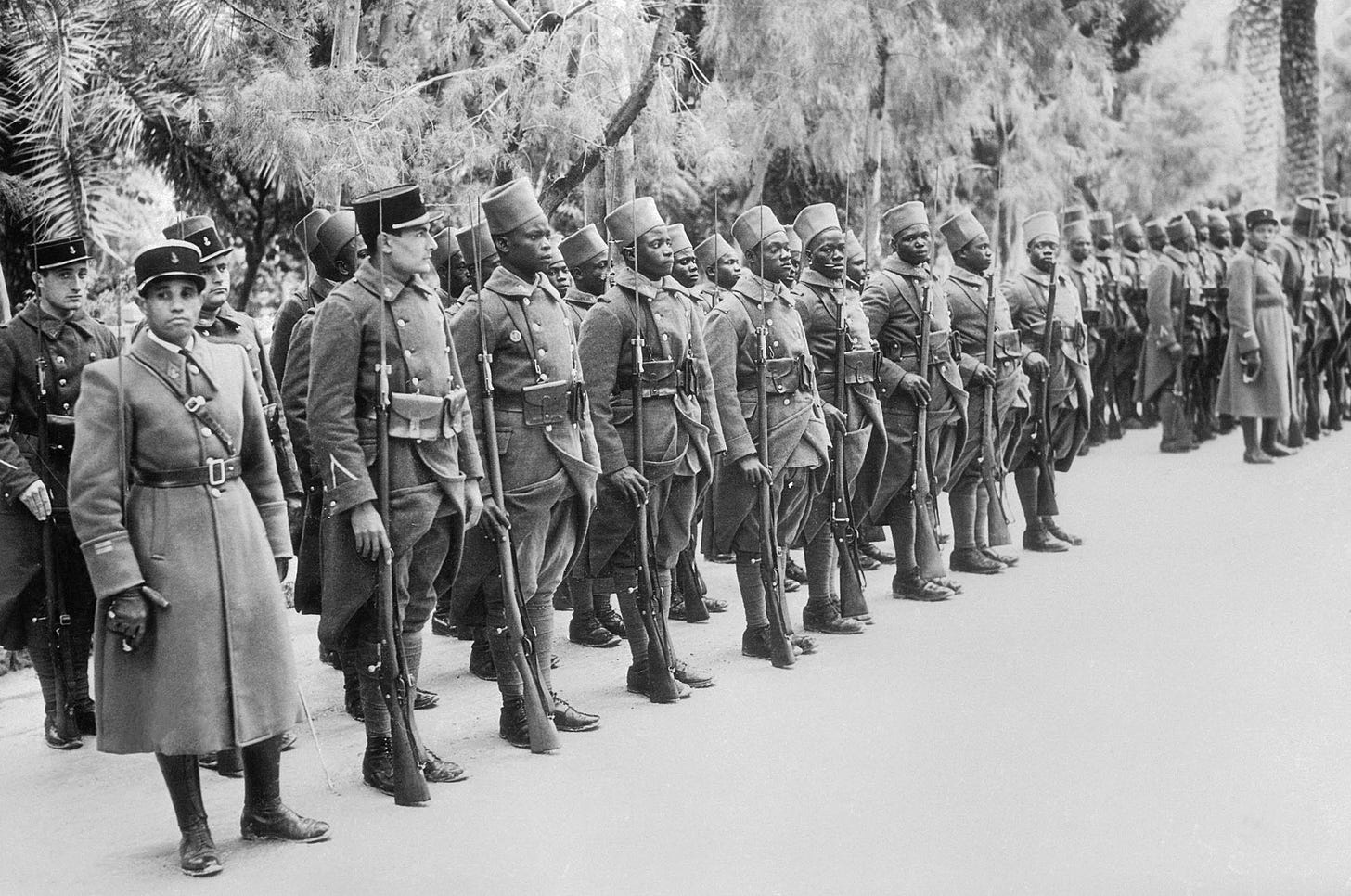

In 1857, the French military began recruiting soldiers from West Africa, forming an infantry unit known as the tirailleurs sénégalais – the Senegalese riflemen.

The name stuck, even though the unit came to include men from all over the region. In World War I, 192,000 tirailleurs fought for France. Of those, 30,000 never came home.

A similar pattern played out in World War II, with 179,000 tirailleurs fighting for France. This accounted for 9% of France’s total fighting force.

Tens of thousands were captured by German forces, and held in prisoner-of-war camps. After they were liberated by the advancing Allies in 1944, they were sent to the Thiaroye military base in Dakar to await discharge.

Living conditions there were poor, and French authorities were slow to deliver the demobilisation benefits that they had promised. So slow, in fact, that it took until 2017 for the surviving tirailleurs to be granted French citizenship, which had been a key aspect of the recruitment drive. Only 28 men were alive to receive it.

On the morning of 1 December 1944, the tirailleurs in Thiaroye protested against their harsh treatment and unpaid wages. The French response was brutal.

Official French accounts say that 35 West African soldiers were killed that day. Other accounts put the casualty count in the hundreds, but the truth has always been hard to establish: for decades, France denied researchers access to its archives, and both French and Senegalese governments at times censored discussion of the massacre.

Neither country included the history of this bitter chapter in school curricula. Nonetheless, Senegal never forgot: not the Thiaroye massacre, and not the extraordinary human sacrifices that Senegal made, over nearly a century, in defence of the French Republic.

As Léopold Sédar Senghor, the country’s first president and also its preeminent poet, put it in Aux Tirailleurs Sénégalais morts pour la France, written in 1938: “They put flowers on tombs and warm the Unknown Soldier / But you, my dark brothers, no one calls your names.”

On 1 December 2024, in a sombre ceremony in Thiaroye – now a suburb on the outskirts of Dakar – Faye brought flowers to mark the 80th anniversary of the massacre.

Macron was not there, but he did send a letter, acknowledging for the first time that what happened in Thiaroye was a massacre.

He did not apologise.

Making history In their successful campaign for the presidency, Faye and his running mate Ousmane Sonko, who is now prime minister, spoke often about French atrocities and unjust policies in Senegal.

This ugly history fuelled some of their Pastef party’s nationalist policies, including the demand to end France’s military presence.

Another key demand is that Senegal withdraws from the CFA Franc, a controversial regional currency that is pegged to the euro. Critics of the currency say that it gives Paris far too much control over West African monetary policy.

These policies found immense popular support, and were a significant factor in Faye and Sonko’s stunning electoral success in March.

They may not be implemented in full: French troops have not left Senegal yet, and Faye is likely to negotiate for some kind of military training and intelligence-sharing deal with France, as well as commercial opportunities.

But by invoking the injustice of the Thiaroye Massacre, Faye is giving himself, and Senegal, the moral high ground – putting the country in a position to extract major concessions.

The lesson for Paris, and other colonial governments, is that its history cannot be whitewashed away: injustices suffered decades and even centuries ago remain a potent political force, with present-day consequences.

It is, perhaps, some small measure of justice for the tirailleurs sénégalais, whose memory was honoured in Thiaroye on Sunday.

Haha good riddance

Given recent high-publicity jihadist attacks in Tchad, plus looking with hindsight at the security situations in Mali and Burkina Faso, how can any government decide that realignment with Russia is a good idea?