Football is far too relaxed about being used for sportswashing

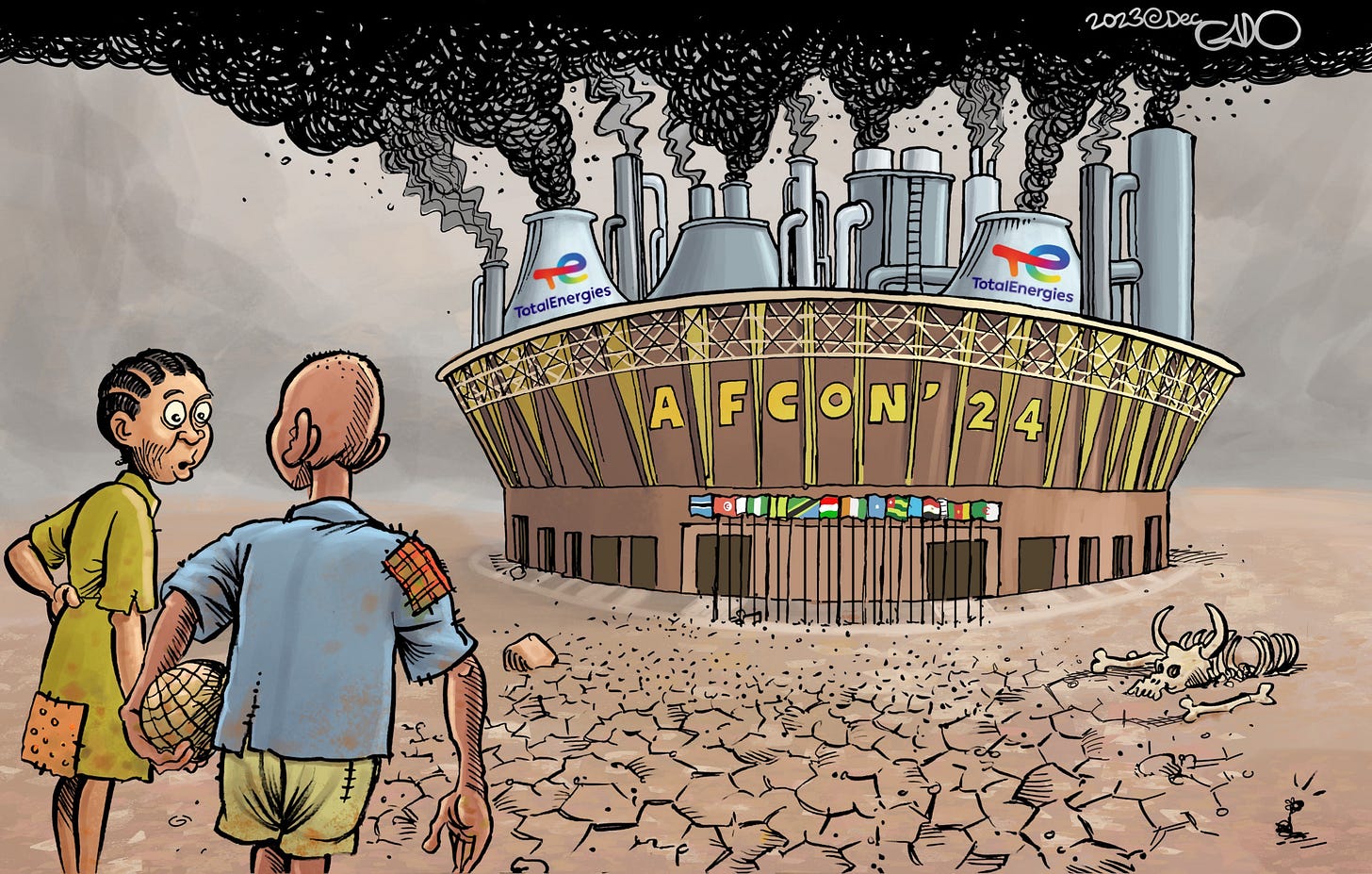

French petro giant TotalEnergies has been sponsoring Afcon for a while now, its largesse distracting the public from the bad press and criticism its core businesses attract

Luke Feltham

Another international football tournament, another dose of sportswashing. This time it’s right in the name. The TotalEnergies Africa Cup of Nations kicked its first ball in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire last Saturday. Over the next month, 24 national teams will vie for the most glamorous trophy on the continent.

The French petro giant – formally just Total – has been sponsoring the tournament for a while now, its largesse distracting the public from the bad press and criticism its core businesses attract.

Like in October, when a criminal complaint of manslaughter was filed in France against TotalEnergies by survivors and family members of victims of the 2021 militant attack in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique near its $20-billion natural gas project.

Officially, the death toll was reported to be in the dozens but journalist Alex Perry found that 1,200 people likely perished in the attack. In the court filings, survivors and relatives of victims accuse Total of failing to take the measures necessary to protect subcontractors and of wilfully failing to assist people in danger. Total has denied all accusations.

Or in East Africa, where residents who live or lived along the path of its EACOP project – a crude oil pipeline running from western Uganda to eastern Tanzania – say they have been stripped of their lands and livelihood. The Climate Accountability Institute estimates that the pipeline will result in 25 times more carbon pollution than the combined current annual emissions of Uganda and Tanzania.

The East African Court declined to hear a legal challenge against TotalEnergies by environmental groups, on the grounds that it was filed too late, but the groups remain vocal in their calls for the company to be boycotted.

But it can be hard to hear such calls over the roar of a cheering crowd, so it’s not hard to understand why “sportswashing” – cleaning one’s image by sponsoring professional sport – is so effective.

Organised sport unites humanity like no other activity. A good 1.5-billion people watched Lionel Messi lift the World Cup in Doha in 2022. In the 90 minutes of a football match, or between the ropes of a boxing bout, we are united in an enthralling collective experience.

United – and distracted.

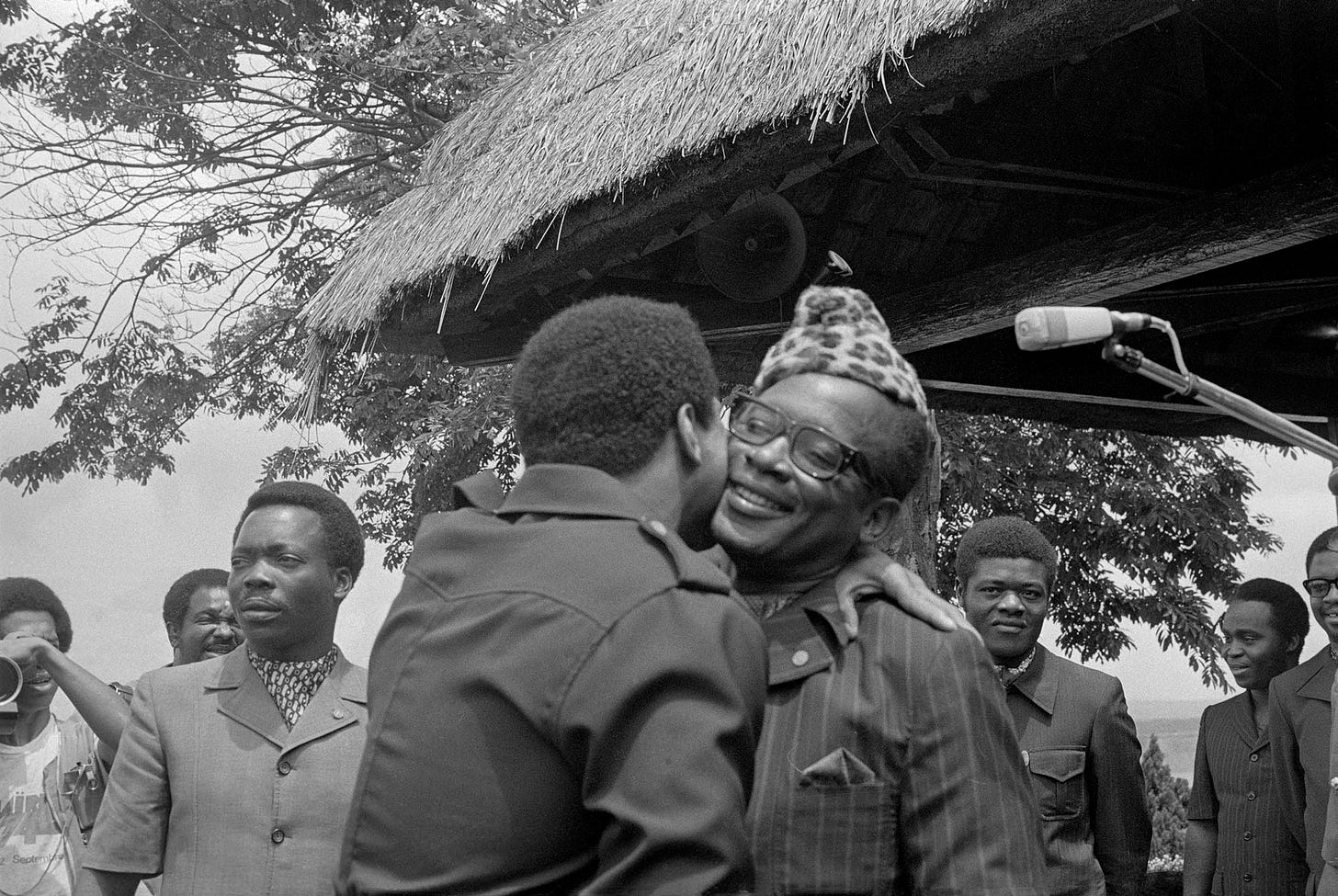

The best known, and perhaps most successful sportswashing venture was 1974’s Rumble in the Jungle. Kleptocrat Mobutu Sese Seko stuffed the pockets of boxing promoters to host the fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman in Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. But the practice dates back to at least 1936 when Adolf Hitler famously hosted the world in Berlin for the Olympics. Results were mixed for Hitler, with black US athlete Jesse Owens claiming four gold medals – effectively giving the middle finger to notions of Aryan supremacy.

Today, sportswashing takes many forms – from suss destinations of Formula One races to football club ownership. Saudi Arabia has risen as the unchallenged champion of this domain. The kingdom needs to diversify its income beyond fossil oils – a depleting resource that is attracting bad press for burning up the planet.

Enter sport, the great “unifier”.

The kingdom will host the 2034 Fifa World Cup. It has already plucked some of football’s stars from the biggest leagues to a competition that has as many viewers as Saudi Arabia has rivers.

Twenty-five of those players – Sadio Mané, Kalidou Koulibaly and Riyad Mahrez, among them – return to the African continent this month to thrill fans in the TotalEnergies Afcon, helping the company get some positive media mentions after the slew of negative ones in recent months.

But we should never forget that sportswashing is a machiavellian tool that is being honed in the games we love.

It is equally malicious in the hands of a morally corrupt prince or a French multinational.