Church, state and dying children

Most Zimbabweans vaccinate their children. But a religious anti-vax view is spreading too.

Jeffrey Moyo in Harare

Melinda and Sindy are married to the same man: Denis Gawe. They go to the same church: Nguwo Tsvuku apostolic church. All three agree on most things. But when their children fell ill last year, their approach differed.

The children showed similar symptoms.

“Red and watery eyes, severe diarrhoea, and dehydration,” Melinda says. Keeping with their church teachings, which shun modern medicine, Gawe diagnosed the children as having been attacked by evil spirits. Melinda had already lost a child to cholera; Sindy had lost three. As the children became sicker, the wives became more desperate. Eventually, they sought medical help in secret. But it was too late.

The children died. Gawe still maintains they were killed by evil spirits, but nurses told his wives the children had contracted measles, a deadly but preventable disease.

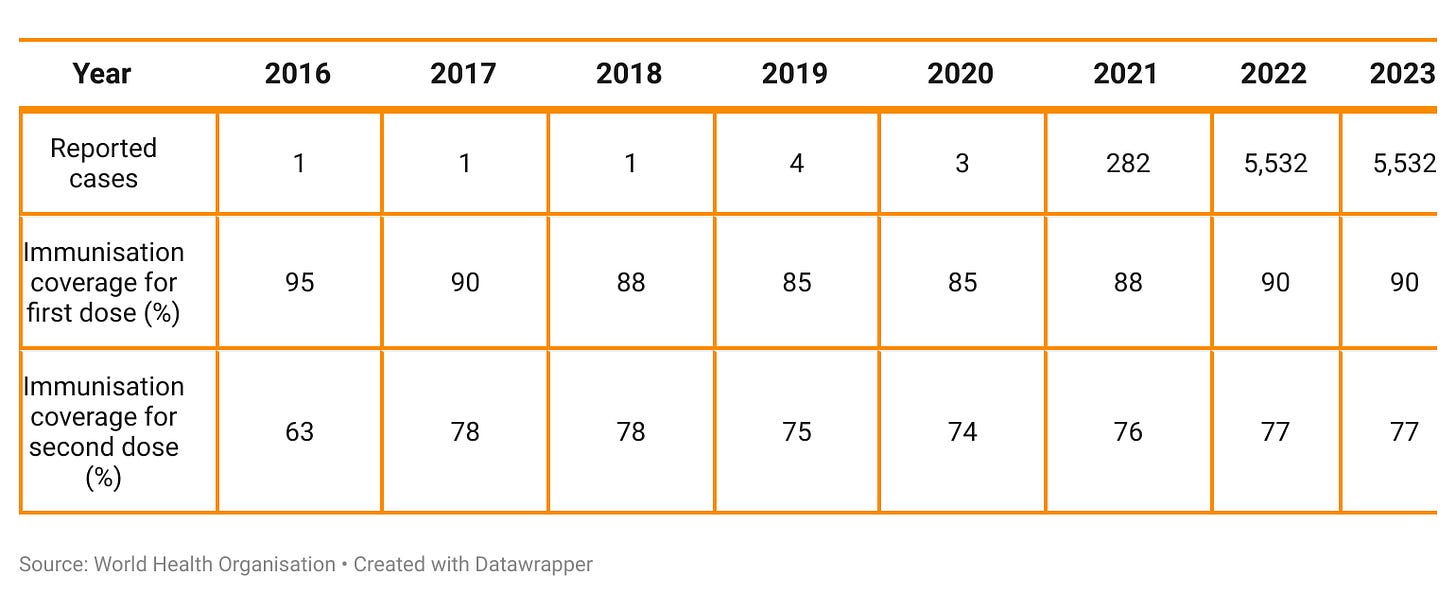

Since 2021, measles infections in Zimbabwe have climbed dramatically, to thousands of reported cases a year, even though immunisation rates have largely held steady.

Religious communities, in which vaccination is discouraged or forbidden, were among those most affected by the recent outbreaks. Health ministry spokesperson Donald Mujiri says the government has reached out to anti-vaccination churches and some members are beginning to embrace immunisation.

But the government’s critics say it doesn’t push the churches hard enough.

“Zanu-PF thrives on huge support from apostolic church-goers and, therefore, can’t punish them for not immunising their children,” says Jessy Mangari, an opposition supporter in Zimbabwe.