Christoph Huber: Accused of DRC war crimes but living easy in South Africa

A Swiss businessman is alleged to have found significant business opportunities in the 1990s war that killed six million Congolese. A new investigation has tracked Christoph Huber to Cape Town.

Ra’eesa Pather, Luvano Ntuli and Jane Borman for Open Secrets

A Swiss businessman is alleged to have found significant business opportunities in the 1990s war that killed six million Congolese. A new investigation by Open Secrets, published here for the first time, has tracked him down to the picturesque southern tip of Africa, where he lives in million-rand homes. He denies wrongdoing.

Christoph Huber is an elusive man. There are just two known photographs of the Swiss national on the internet. In one undated photo, he wears large aviator sunglasses with a broad grin on his face, but the man who Swiss authorities are investigating for war crimes sits on a leafy patch that does nothing to give away his location. For years, journalists have speculated that the secretive businessman lives in South Africa. There is one clue in the photograph that hints this may be true: the logo of South African clothing brand K-Way on Huber’s khaki shirt reveals that he has spent time in the country.

Now, a new investigation by South African non-profit Open Secrets, published exclusively in The Continent, has found concrete evidence of his residence in the country.

Huber has a South African ID number and owns four properties in the Western Cape province. The title deeds, which Open Secrets reviewed, confirm he co-owns the properties with his wife.

In a luxury gated community in the affluent Somerset West area of Cape Town is Huber’s most expensive property in the country: a home bought in May 2018 for R16-million. At the time, the couple already owned another property five minutes away: a house perched on a hill with panoramic views that was bought in 2002 for R3.1-million. They also own property in Stellenbosch and Struisbaai, a small coastal town around 200km away from Cape Town. The four properties are worth at least R25.7-million ($1.4-million) based on their purchase prices alone.

Huber has been a person of interest for human rights advocates since the 1990s. Several groups including a United Nations panel of experts, Global Witness, United States law firm Amsterdam & Partners, Trial International and Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI) have accused him of illicit exploitation of minerals in the east of the DRC. Six million Congolese people have been killed since 1996 in wars fuelled by the scramble for the country’s minerals.

States law firm Amsterdam & Partners, Trial International and Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI) have accused him of illicit exploitation of minerals in the east of the DRC. Six million Congolese people have been killed since 1996 in wars fuelled by the scramble for the country’s minerals.

It is one of the oldest documented war crimes, but for decades no corporate actor has been tried for it despite well documented evidence that illicit trade in natural resources fuelled war in places like Angola, DRC, Iraq, East Timor, Myanmar and others. If Swiss authorities, who opened their own investigation in 2019, go on to indict Huber it would be the first trial of a corporate actor for pillage since the Nuremberg trials for Nazi crime in 1940s Germany.

The Swiss attorney general’s office has not said whether or not Huber will be indicted and Huber, through his lawyer, denied any role in illicit mineral trading. “Our client denies that he has ever been involved (consulting, being employed or in any other manner) with any company that has traded illicitly sourced minerals,” said a letter to Open Secrets in June.

His lawyers also threatened legal action against Open Secrets to halt the publication of their findings, including a threat to request a punitive cost order from the high court in Cape Town.

A pricey view

The complaint before Swiss authorities alleges that Huber illegally smuggled minerals out of the eastern DRC between 1998 to 2003, during the Second Congo War. He bought his first Somerset West home during this period but, through his lawyers, he denies any of his properties have any relevance to allegations of criminality against him. “We further struggle to understand the relevance of the mentioned properties our client may or may not be the registered owner of,” the letter from Huber’s lawyer said.

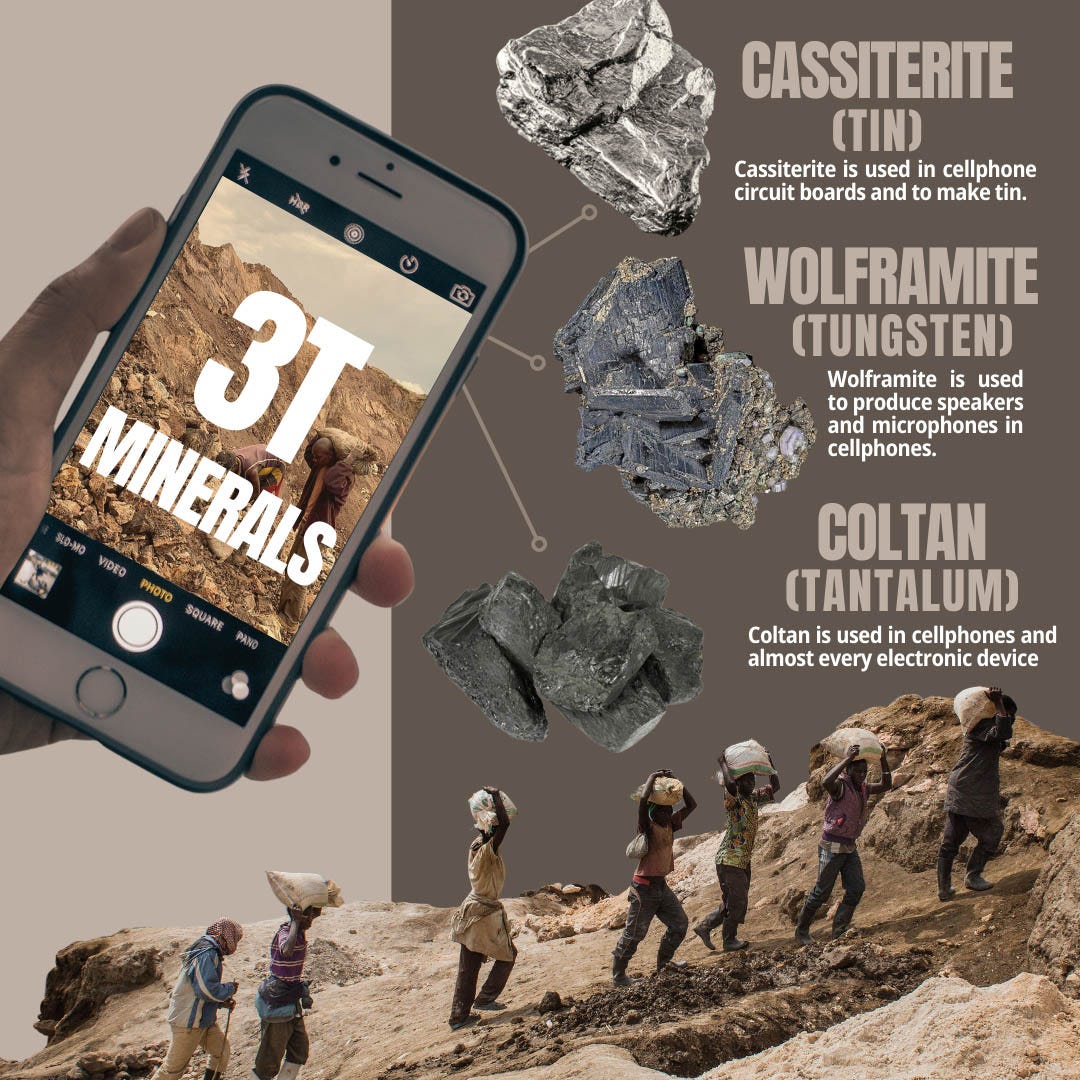

The first and second Congo wars were among the most intense periods of plunder in the DRC in recent memory. Neighbouring states, rebel groups, private companies and individuals descended on eastern DRC to illicitly mine for diamonds, gold, cobalt and coltan in conflict zones and spirit it out of the country under the cover of war that many of these parties were contributing to.

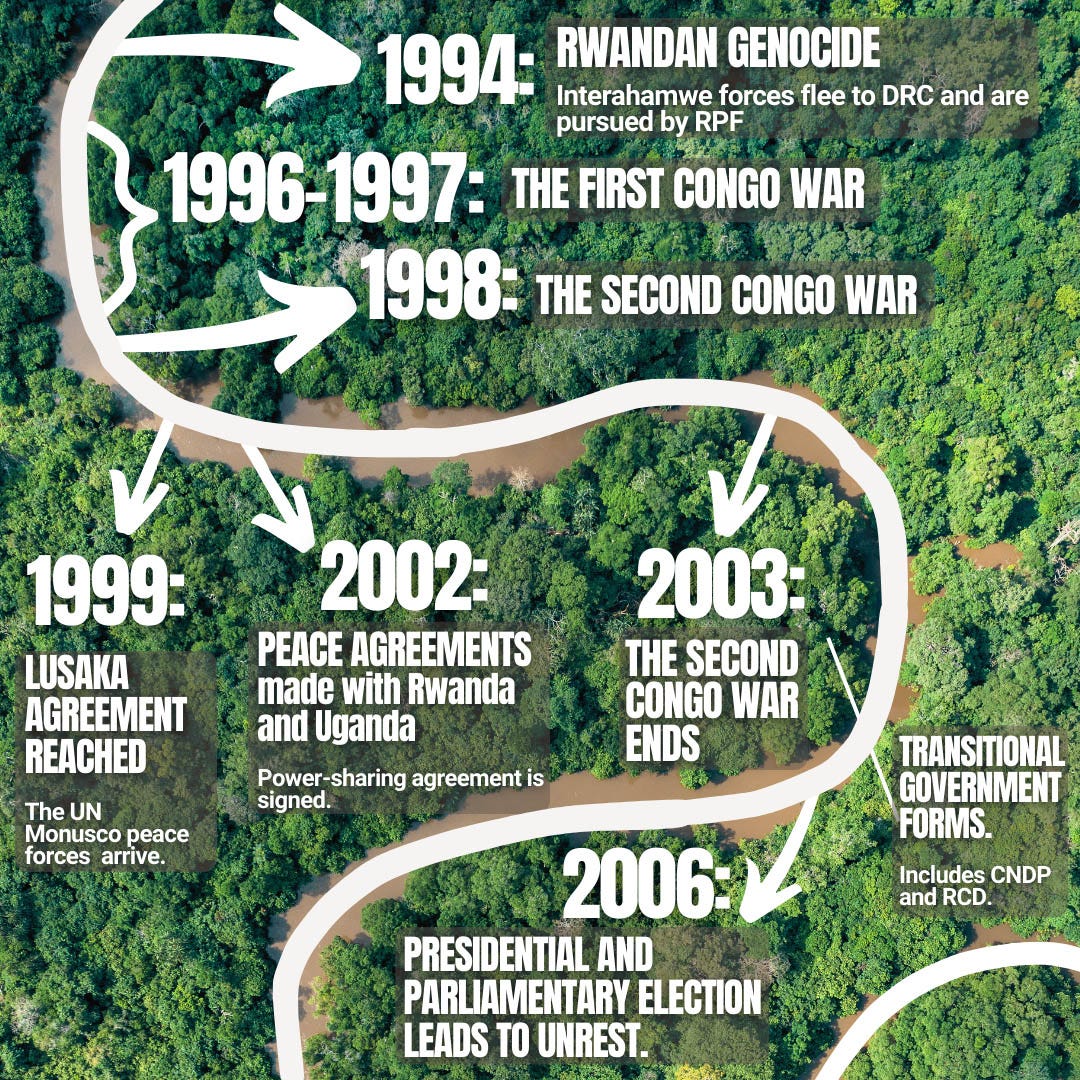

Waves of conflict in the eastern DRC had been triggered by the end of the 1994 genocide in neighbouring Rwanda. When the Rwandese Patriotic Front (RPF) led by Paul Kagame took power in Kigali and stopped the blood-letting, nearly two million Hutu refugees fled to the DRC.

They included Hutu perpetrators of the genocide, and other members of the ethnic group who feared reprisal killings from the victimised Tutsi.

The RPF, supported by soldiers from Uganda and Burundi, began operations in eastern DRC to pursue Hutu militants and other perceived security threats. Claiming that the Congolese president of the time – flamboyant kleptocrat Mobutu Sese Seko – had given refuge to perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide, these troops also aided his ousting and replaced him with Laurent Kabila as president in 1997. Kabila was assassinated in office four years later and replaced by his now better known son, Joseph Kabila.

Taking advantage of the instability in Kinshasa, the armed groups in the eastern DRC began a scramble to occupy land and loot mines under their control. According to the Trial and OSJI criminal complaint to Swiss authorities, Huber found significant business opportunities in this environment.

Kigali connections

Their complaint to Swiss authorities claims that Huber’s alleged pillage has been executed through various close links he has with Rwanda.

“Our investigations unveiled corporate documents, as well as internal paperwork belonging to the RCD-Goma, which demonstrate Chris Huber’s business dealings with the armed group,” Trial’s former head of investigations and litigation, Bénédict De Moerloose, said in 2019. RDC-Goma – Rally for Congolese Democracy – was an armed group that evolved into the Kigali-backed M23 movement.

Documents obtained by Trial and the OSJI show that, in February 2001, Huber signed a contract on behalf of Rwandan company Medivals Minerals with Sominki – Société minière et industrielle du Kivu – a Congolese state-owned company. The Congolese company owned more than 100,000 km2 of mining rights for coltan, cassiterite and wolframite in North and South Kivu in the eastern DRC that had been occupied by RCD-Goma in 1998. The group had seized Sominki in the process.

The Sominki agreement gave Medivals Minerals four mining concessions and allowed it access to mineral treatment facilities. At the time, soldiers of RDC-Goma illegally administered the concession areas through a pseudo government structure. Trial and the OSJI believe Medivals Minerals went on to extract minerals from concessions illegally controlled by RCD-Goma, saying Huber was “able to acquire hundreds of tons of cassiterite and wolframite during the time where he held concessions”. In doing so, Trial and the OSJI claim that Huber was complicit in plundering minerals from conflict regions of the eastern DRC during the Second Congo war. One year after Huber signed the Sominki agreement, he purchased the first Somerset West home.

Huber was also listed in the groundbreaking 2009 report on plunder in eastern DRC, produced by the UN Group of Experts on the DRC. It said that African Ventures Ltd, a company which hired Huber as a consultant, had bought minerals from a Chinese business, Huaying Trading Company (HTC), which sourced cassiterite from areas controlled by the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda – the Hutu armed group that the Rwandan army pursued into the DRC after the genocide. Huber, through his lawyer, said that the HTC shipments from conflict zones referenced by the Group of Experts were never supplied to African Ventures Ltd.

If Swiss authorities go on to indict Huber it would be the first trial of a corporate actor for pillage since the Nuremberg trials for Nazi crime in 1940s Germany.

The most recent accusations against Huber are contained in an investigative report commissioned by the current DRC government. Published in April, the report by US law firm Amsterdam and Partners details alleged mineral smuggling in the DRC and names Huber 33 times, calling him and his business associate “the backbone of Rwanda’s smuggling networks in central Africa.”

The April report includes the testimony of Jaraslav “Jerry” Fiala, a Czech geologist who was Huber’s business partner at a Rwandan mining company called Rudniki. Fiala accuses Huber and his associates of laundering DRC minerals through Rudniki to sell them on the international market as originating in Rwanda and therefore conflictfree. Huber and Russian businessman Simeon Briskin bought shares in Fiala’s Rudniki and reportedly traded more than $150-million through it, even though it was producing only a moderate amount of tantalum and tin from Rwandan soil. An investigation by Global Witness in 2022 had made similar findings to Amsterdam & Partners.

Huber, through his lawyers, denied laundering minerals through Rudniki and said that Fiala was an unreliable witness because – in separate arbitration proceedings that never dealt with his claims against Huber – the arbiter found the Czech geologist’s evidence unreliable.

Huber, through his lawyers, dismissed the Amsterdam and Partners investigation as a copy of the Global Witness report with “no evidence to support their findings”.

And the South African government, which has sent troops to eastern DRC to intervene in the war which is still fueled by a scramble for Congolese minerals, has not looked into allegations against Huber.

As Swiss authorities continue their slow-paced investigation into Huber’s suspected war crimes, Congolese people in the eastern DRC continue to live in violence, waiting for the day when the minerals in their land finally become theirs.