Chagos Islanders confront their postcolonial future

Some Chagossians wonder if they are just trading one coloniser for another.

The dream is within touching distance. Olivier Bancoult has pulled off a feat many would once have considered impossible – his people are on the brink of being allowed to return to their fabled homeland of Chagos.

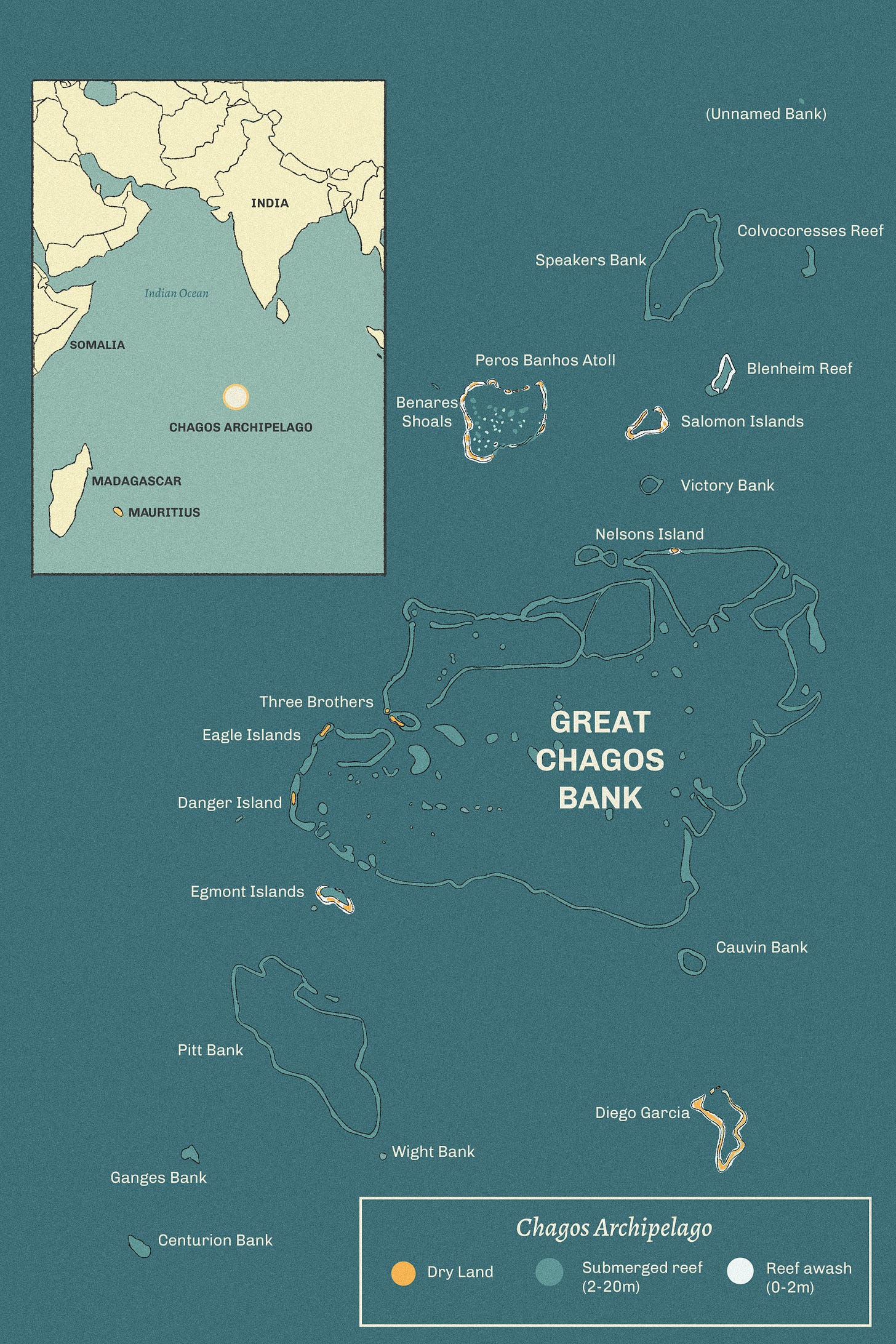

Half a century ago, as its empire crumbled, Britain held tight to the tiny Indian Ocean archipelago, which straddles one of the world’s most important maritime trading routes. The fading imperial power leased one of the islands, Diego Garcia, to the United States for a military base. Its inhabitants were brutally evicted and dumped in Mauritius and the Seychelles, with little more than the bags they could carry. They were never allowed to return, and the community is now scattered between Britain, Mauritius and the Seychelles.

Bancoult, 59, has devoted much of his adult life to fruitless battles in the British courts to reverse that. His fortunes shifted in 2019 at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) after he changed tack. He helped Mauritius, which is more than 2,000 kilometres from Chagos, to win sovereignty from Britain. Mauritian authorities have promised to allow the Chagossians – some 10,000 people – to return home.

It is not immediately clear how many Chagossians will take up Mauritius’ offer to return home. “The numbers are not important,” said Bancoult. “It’s the right to live in the place.”

At first glance, it seems like the perfect postcolonial win-win.

As sovereign, Mauritius is eyeing tantalising opportunities for Chagos in fishing, ecotourism, rare earth exploitations and foreign naval operations. The future landlord is already negotiating a potentially lucrative deal that will allow the US to continue operating its military base, for a monthly rental in excess of the $63-million that Washington pays for a smaller base in Djibouti.

Chagossians on the other hand get justice. Bancoult is meeting Mauritian Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth on a monthly basis for updates on the high-level handover talks with Britain. He foresees that Chagos will enjoy some form of regional autonomy similar to Rodrigues, another Mauritian dependency.

“My vision is that Chagossians will have their destiny,” said the long-time leader of the Chagos Refugees Group (CRG), speaking at his office in the Mauritian capital Port Louis. But he cautioned patience. “Everything will not happen at once.”

Even when Mauritius officially gets the keys to the archipelago, there will be plenty of work to do. The islands’ infrastructure must be rebuilt; the thorny issue of reparations, for decades of suffering, must be settled once and for all.

But some Chagossians are not convinced that justice is in sight at all.

‘They talk ... like we’re still slaves’

In Roche Bois, an impoverished suburb of Port Louis, a group of Chagossians sit on a corrugated iron patio, hotly debating their future. These Chagossians belong to a group called Chagos Asylum People, led by Claudette Pauline Lefade. She used to be part of Bancoult’s CRG; now she works in direct opposition to it. There is a sense of disillusionment among members, who feel that Bancoult and the CRG have sold them out. Bancoult oversees a welfare fund that receives an annual grant of seven million Mauritian rupees ($158,000) from the Mauritian government and Lefade views him as beholden to that government.

“We need to take part in the negotiations,” Lefade says. “They cannot decide behind our backs as they have done throughout history.”

Instead of preparing for a return to Chagos, Lefade is helping her members apply for British citizenship and training opportunities. Britain has recently relaxed citizenship requirements, which were previously restricted to first and second generation Chagossians. The charm offensive is belated but still offers an escape from decades of impoverished exile for some in the community.

Some Chagossians are not convinced that justice is in sight at all.

Lefade is working closely with the UK-based platform Chagossian Voices. For Mauritius, sovereignty over Chagos would “be like manna from heaven”, said Frankie Bontemps, one of the platform’s leaders, based in Crawley, near Gatwick Airport – home to about 3,000 Chagossians. “They’ll have this long-term lease with the US. I don’t think they have any long-term goals for Chagossians themselves.”

Chagossian Voices is instead fighting for recognition as an indigenous people at the United Nations and at other international forums, a claim based on generations-deep links to the slaves who arrived on the archipelago in the 1700s. Indigenous status, so far denied by both Britain and Mauritius, would provide legal underpinning for self-determination.

Loath to trust Mauritius, Bontemps reserves equal ire for Britain. He points out that a £40-million fund set up in 2016 to improve the lot of Chagossians, proved so byzantine that less than £1-million has been disbursed. And he dismissed British claims that Chagossians had been consulted during negotiations, saying that this amounted to a few online meetings in which participants’ concerns were repeatedly batted away.

“They talk to us like we’re still slaves, like they think we’re stupid,” said one member of Chagossian Voices after the second consultation meeting in May, which was observed by The Continent.

Geopolitical jostling

Scepticism over Mauritian control is shared by Chagossian communities in the Seychelles, who worry that it would leave them permanently sidelined. Pierre Prosper, the head of the Chagossian Committee Seychelles, is concerned that his group will lack leverage in the Mauritian legal system. “We want a clear say on what happens to us,” he said.

This year, Bernadette Dugasse – a Chagossian born in Diego Garcia, who had been exiled in the Seychelles and has no links to Mauritius – launched a legal bid at the London High Court to halt the negotiations between Mauritius and Britain. The suit argued that the British government’s ongoing failure to hold “substantive consultations” with the islanders breached human rights law.

She would rather that the islands remain under British control until such time that Chagossians can assume full sovereignty themselves. At the time of writing, she was waiting for a judge to rule on her application.

“We’re not ready to rule our island ourselves. But we still want the British government to be there to help us make the transition,” she said. “Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t know.”

Dugasse’s challenge had an intriguing geopolitical backdrop, having been encouraged by British Conservative MP Daniel Kawczynski, who had his own motivations for throwing a spanner in the works. He fears that Mauritian sovereignty would open the door to Chinese influence in the Indian Ocean.

Former British prime minister Boris Johnson made the same argument in a recent newspaper column, in which he said that Britain is making “a colossal mistake”. He wrote: “A future Mauritian government might close the base or allow the Chinese, at the right price, to build their own runways on the same archipelago.”

“We’re not ready to rule our island ourselves. We want the British government to be there to help us make the transition”

These claims seem wide of the mark – if anything, Mauritius is closer to India, having allowed New Delhi to build a military base on Agalega, another of its other island dependencies. On the margins of the Chagos negotiations, there has also been talk of a new Indian Ocean entente that would align Mauritius and India with British, American and Australian interests in the region.

As for Chagossian interests? “It’s an interstate dispute and that’s the problem,” said Gareth Price, a senior research fellow at London-based think tank Chatham House. “Chagossians are the pawns in all this.”