Africa’s identity crisis

Biometric tech – like iris scans and facial recognition – is meant to make governments work better for citizens. It has fallen short. And it has been abused.

Beatriz Ramalho da Silva and Tomas Statius

Every country has a system to identify the people who live within its borders. Things like birth certificates, identity cards and passports allow people to prove that they are who they say they are – and they access government services.

For decades, these systems have been based on paper. If you don’t have the right piece of paper – or that paper does not have the right stamp, or if the correct f iling cabinet cannot be located – then proving your identity is an administrative nightmare. And papers are easily forged.

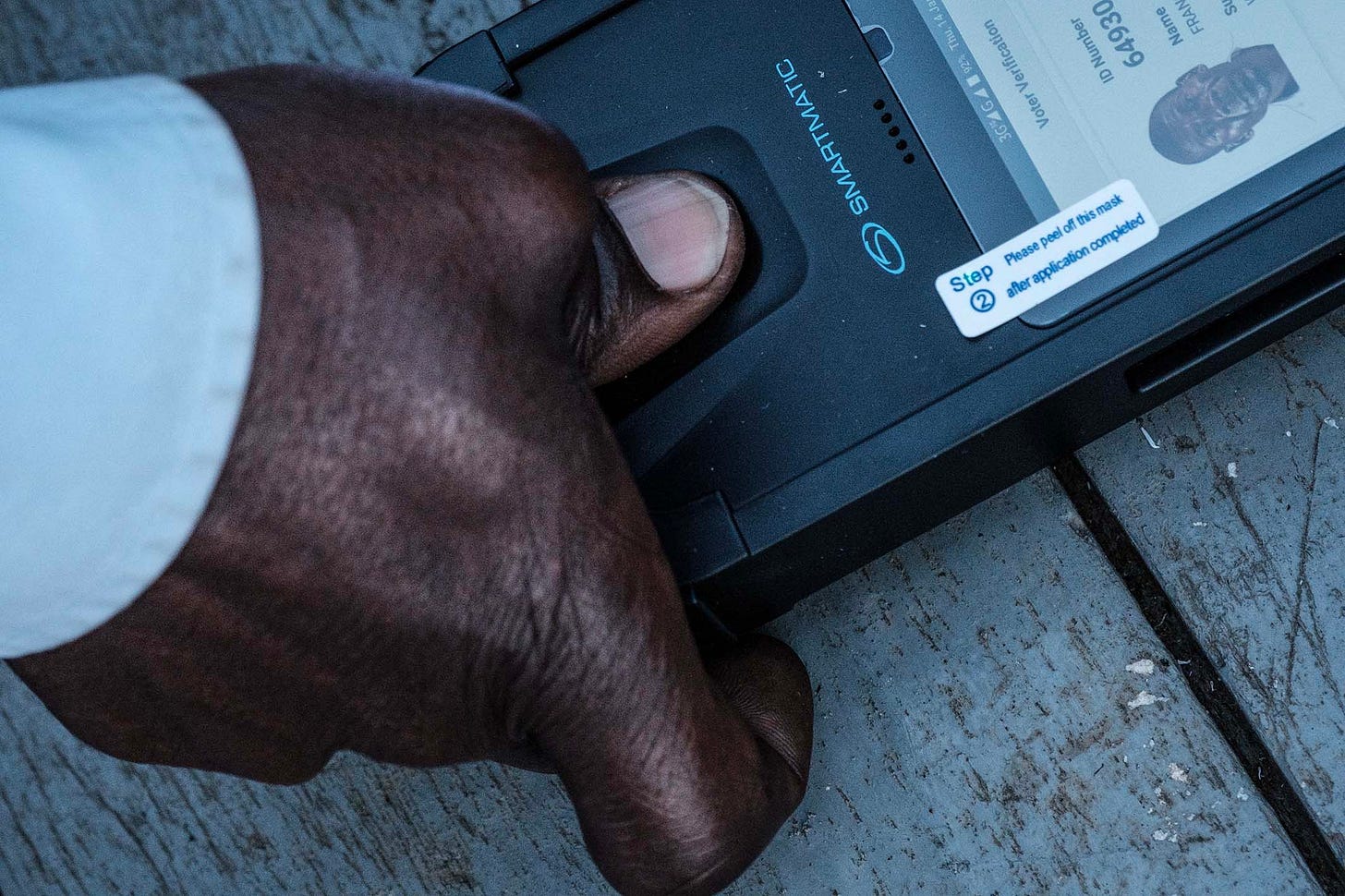

Biometric technology is meant to change all that. The digital technology uses a person’s physical characteristics – their f ingerprints, their face, the pattern of their retinas – to confirm their identity. Used properly, it allows governments to build reliable population registers and voter rolls, and deliver services more effectively. It should make it harder for criminals to commit identity fraud, and for elected criminals to commit electoral fraud.

That’s the theory, at least, and may explain why governments around the continent have been enthusiastically embracing biometric technology.

At the recent ID4Africa Conference in Cape Town, delegates from 50 African countries – including numerous government procurement officials – rubbed shoulders with hundreds of predominantly non-African companies. Speakers enthused over the technology’s potential to improve governance and protect human rights. The atmosphere was thick with discreet deal-making as states queued up to spend their resources on new solutions to old problems.

Except the solution may not be as transformative as promised. A year-long investigation by Lighthouse Reports and Bloomberg – shared with The Continent – examined three high-profile attempts to roll out biometric technologies on the African continent. All are cautionary tales.

Big promises

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, a bewildering trail of blockbuster deals to print national ID cards has resulted in plenty of money changing hands – but only a handful of national ID cards to show for it. The country has had no functional civil registry for decades, which can make it difficult for citizens to do things like open bank accounts or receive money from abroad.

Successive governments have promised increasingly expensive ID schemes to solve these problems. But to date no successful ID rollout has occurred. One such scheme involved the Belgian company Semlex, which has previously been implicated in corruption scandals on the African continent. In 2014, it presented the president at the time, Joseph Kabila, with a deal to roll out national ID documents in return for a lucrative contract to print passports. Kabila took the deal.

Passport sales began, but soon sparked controversy: Semlex charged $185 per passport, among the most expensive in the world, of which $60 went straight to Kabila’s family, according to a Reuters report in 2017.

Sources told Lighthouse and Bloomberg that instead of funding national IDs, passport profits were diverted to the construction of the Hypnose luxury shopping mall in Lubumbashi – seen as a safe way for Kabila to store his money.

Neither Semlex nor Kabila responded to requests for comment.

Kabila’s successor, Félix Tshisekedi, initiated a second round of ID card procurement. This resulted in a blockbuster $1.2-billion deal, initially reported as being awarded to French company Idemia and local partners.

But as civil servants raised the alarm about financial irregularities and the risk of an “enormous scam” – and with the World Bank refusing to fund the project – production of IDs quickly ground to a halt. Only Tshisekedi himself and a few hundred VIPs ever received ID cards.

When contacted, Idemia said that it “is not a party to any contract” with the Congolese government, but does currently have a contract with Afritech, a Congolese company, to build Congo’s civil registry and print ID cards. A spokesperson for Tshisekedi declined to comment.

Same old problems

The government of Mozambique turned to biometric technology to address concerns with the credibility of its elections. It issued a series of multimillion-dollar contracts to procure biometric voting equipment. But the new technology appears to have had the opposite effect – creating new ways to f ix electoral results.

Artes Gráficas, a company owned by businessmen with close ties to the ruling party, Frelimo, won the contract to provide electoral equipment ahead of the 2018 election. It partnered with a South African tech vendor, Laxton, to provide a voter registration kit ahead of presidential elections.

But the process was marred by irregularities, which included inflated voter numbers in areas sympathetic to the ruling party.

Sources inside the government, and former employees, claimed that Laxton was aware of these issues. Yet, in 2023, Laxton won an “exceptional” no-bid tender for $127-million, to provide a new set of voter registration technology. Behind the scenes, internal documents and meeting minutes reveal there were serious concerns inside the government electoral body over Laxton’s equipment and the technology’s value for money.

After the 2023 local elections – won by the ruling party – the main opposition party condemned a “massive electoral fraud”, while both civil society and international observers highlighted the presence of hundreds of thousands of “ghost voters” on the voters roll.

This was exactly the kind of irregularity that the new biometric system was supposed to eradicate.

A Laxton spokesperson said that its system had been reviewed and approved by numerous stakeholders, “including government agencies and multiple political party representatives”. The company said it had carried out “the successful registration of a record 16.8-million voters” and that “alleged isolated incidents do not reflect the overall success and reliability of the system”.

Surveillance state

In Uganda, a new national ID system ended up feeding a sweeping surveillance state built in co-operation with Huawei. The $126-million deal resulted in a network of closed circuit television cameras built across the country, which has given it the capacity to deploy facial and number-plate recognition technology. Meanwhile, sensitive personal data – like that required to register a sim card or make a bank transaction – can be accessed at will by state actors with no due process.

Biometric tools, now central to many of the day-to-day functions of the state, have become a powerful mechanism for surveilling politicians, journalists, human rights defenders and ordinary citizens. One of them is Nick Opiyo, one of East Africa’s leading human rights lawyers. “There’s almost no confidentiality in my work any more,” Opiyo told Bloomberg. “There’s pervasive fear and self-censorship.”

Neither Huawei nor the Ugandan government responded to requests for comment.